Chinese porcelain: the soul of an ancient art

Chinese porcelain first developed during East Han Dynasty (25-220 AD). To make porcelain, mineral-rich clay or kaolin is fired in a kiln at temperatures of over 1,200 °C, until a layer of glaze is formed on the surface, onto which patterns are then carved or painted. Creation of a good chinese porcelain piece takes the right combination of the physical conditions, skill, and sheer luck.

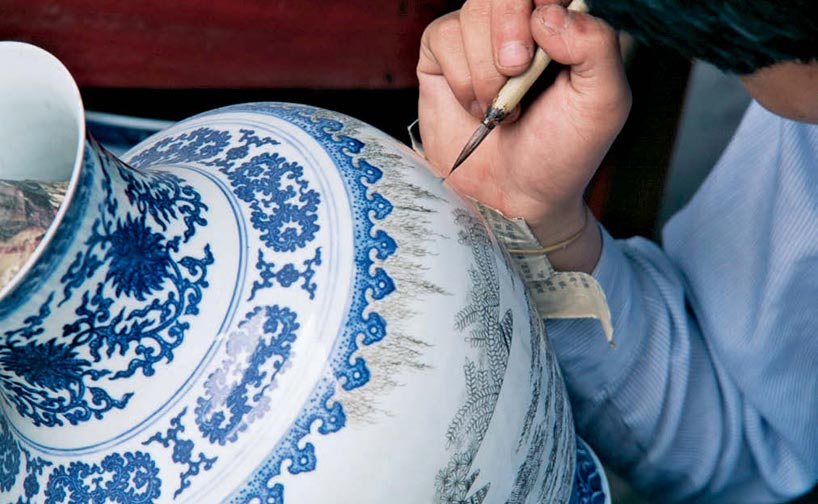

As the spotlessly white porcelain clay is thrown on the turntable in deft rotations, the carving knife, turning and flying, creates a harmonious rhythm along the rim of the bowl. It only takes an instant to create an exquisite piece – be it a bowl, a plate, or a vase.

This is the Traditional Kiln Exposition Area in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, where tourists are shown the complete process of making porcelain. As the world-renowned “Porcelain Capital”, Jingdezhen attracts thousands of tourists from around the world.

As artifacts of Chinese porcelain spread ever wider around the world, more and more people appreciated these works of exquisite craftsmanship. They are precious pieces of art that China has contributed to the world.

When Europeans came to Jingdezhen in the 18th century, they were stunned by the beauty of the porcelain. As Jingdezhen was then also known as Changnan, people began to call porcelain “china”. Since then, “china” has stood for both porcelain and China – a country of beautiful porcelain. It used to be a daily necessity of ordinary Chinese people. It is the most familiar impression that China has given the world.

The soul of an art

Porcelain first developed during China’s East Han Dynasty (25-220 AD). It gradually evolved from pottery, as the ancient potters experimented with different pottery techniques. To make porcelain, mineral-rich clay or kaolin is fired in a kiln at temperatures of over 1,200 °C, until a layer of glaze is formed on the surface, onto which patterns are then carved or painted. The complex changes that occur during the firing process are very difficult to predict. Creation of a good Chinese porcelain piece takes the right combination of the physical conditions, skill, and sheer luck. Pieces of superior patterns, texture and colors are life-long dreams of a craftsman. Not surprisingly, since ancient times, porcelain has been considered China’s fifth great invention — the others being the compass, gun powder, movable type, and paper.

Chinese porcelain continuously develop from the Shang Dynasty (1765-1122 BC) through the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368-1911), reaching its pinnacle during Song Dynasty (960-1279), a period that produced the “Famous Five Porcelain Types” of all times: Ge ware, Guan ware, Ru ware, Ding ware, and Jun ware. Ge ware has a relatively uneven, crackled surface, with interspersed crack lines popularly referred to as “golden floss and iron threads”. Characterized by pinkish-green glazing, Guan ware is of simple and elegant design. Ru ware uses thick, fleshy glazing, and is predominantly azure blue. Ding ware is entirely white and is marked by decorative patterns stamped or incised into the clay. The invention of Jun ware had to do with Emperor Huizong of Song Dynasty, who once had a dream in which he was impressed with the beautiful colors of the sky after a rain. He ordered his craftsmen to make Chinese porcelain ware with hues of red and blue that would look just like the beautiful sky colors in his dream. The unique characteristic of Jun ware is that the colors are all formed during the firing process. Jun ware has always inspired admiration, as reflected by the popular saying, “You can put a value on gold, but not on Jun.”

The ingenuity and strength of Chinese people have been shown again and again, as they have fired life into as plain a material as clay.

“Blue decoration is painted on the unglazed body, the brush now heavy now light. Peony flowers are painted on the vase body, like your fresh makeup.” This popular Chinese song is about the finest porcelain – blue and white porcelain. This uniquely Chinese blue-and-white ware represents Chinese porcelain culture. For centuries, it has been used and collected inside and outside of imperial palaces. Foreign friends call it “China’s national porcelain”. Blue and white porcelain was first developed during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), went through rapid development during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) and then gradually reached its technical maturity.

Blue and white Chinese porcelain is crafted in a unique process. Before glazing, beautiful decorations are painted onto the body of the porcelain with a brush using specially made, grayish-black pigments. The decorations are sometimes elegant and sometimes unrestrained. After the glazed body is fired at a temperature of 1,200 °C, blue-and-white patterns emerge, reminding one of traditional Chinese wash painting, with a fluency of expression that is clear, simple, elegant, unobtrusive, and gentle. Before the reign of Ming Dynasty’s Yongle Emperor, the decorations on blue and white porcelain plates were always realistic paintings. During Yongle Emperor’s reign, (1403-25) decorations appeared that depicted flowers and fruit, or scenes of the four seasons, together, as an expression of people’s yearnings for the good things in life. This marked the beginning of a new era in the development of blue and white porcelain. The word qīng (referring to either blue or green) had a special meaning in ancient China. Intellectuals hoped to excel their teachers, as “the color blue comes from the indigo plant but is bluer than the plant itself.” Once they embarked on an official career, they hoped for promotion “as rapid as a cloud swooping to lofty heights in the blue sky”. This gives an idea of the weight of the word qīng (青) in the hearts of Chinese people.

Nowadays, elements of blue and white Chinese porcelain have been extended, as a symbol of Chinese culture, to various aspects of people’s daily life, including songs, clothing, and mural paintings. Inside of Beitucheng Station of Beijing’s Metro Line No. 10, the platform decorated with patterns in the blue and white porcelain style looks fresh and elegant. On the runways of the International Fashion Week shows in New York, London, Paris, and Milan, clothes with blue and white porcelain patterns have attracted much attention.

A medium of civilization

In 851 AD, an Arabian merchant described to his compatriots a piece of Chinese porcelain vase he had seen: “It is as transparent as a vase made of glass. The water inside of the vase could be seen from outside, and yet the vessel was only made from clay!” No historical record exists that indicates which Chinese kiln had produced this particular piece of china. Starting from Tang and Song Dynasties, Chinese porcelain was exported in large volumes, becoming the third largest export commodity, after silk and tea. A few hundred years after that Arab merchant, his descendants were finally able to see large quantities of porcelain ware coming from China. Most of these pure and smooth vases and plates had come from Jingdezhen, in the northeast of China’s Jiangxi Province.

Jingdezhen has a history of producing porcelain that goes back over a thousand years, to the Five Dynasties period (884-978 AD).

Jingdezhen became the center of China’s porcelain industry, of which people used to say: “To it craftsmen come from four directions; from it vessels go to all parts of the world.” Its porcelain has been renowned throughout the world for its “mirror clarity, jade whiteness, paper thinness, chime stone sound”. A French missionary described the impressive sight of porcelain manufacturing: “In the day, heavy smoke hides the clouds; at night, fires in the kilns redden the sky.”

In ancient Chinese history, the most beautiful and rarest items were usually imperial monopolies. During the reign of Ming Dynasty’s Hongwu Emperor (1368-99), the first official kiln was built in Jingdezhen, to make Chinese porcelain exclusively for the Forbidden City. Imperially operated, it employed the best craftsmen in the country and the best porcelain clay, and produced porcelain ware for the exclusive use of the imperial household, outside of which the use and selling of these porcelain items were forbidden. The formulas and the firing methods, too, were strictly guarded secrets. In order to prevent the imperial ware from being circulated outside the imperial household, items with flaws were destroyed and buried. Those that finally made it to the imperial palace as articles of tribute had passed a series of stringent examinations. Later, Zhu Di, Chengzu of Ming Dynasty (Yongle Emperor), became the first to use porcelain bowls during meals instead of jade bowls.

The establishment of official kilns laid the foundation for the prominent role that porcelain has played in Chinese history. Waves of overseas merchants came to China from far distances in order to make a fortune.

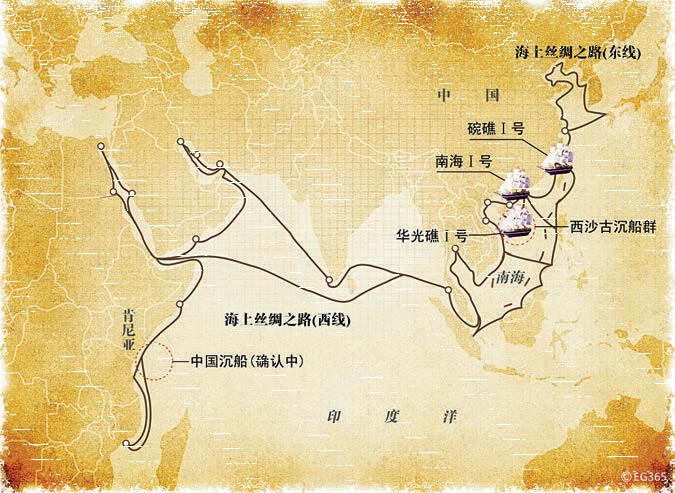

The final porcelain products were transported to the far corners of the world. Ships of Persia, Portugal, and Britain departed from trading ports such as Yangzhou and Guangzhou, fully loaded with items of high value, and sailed to different parts of the world, bringing not only porcelain ware but also the technology for making it.

This trade route on the sea with Chinese porcelain as the main commodity has been called the “Silk Road of the Sea” by later generations. Via the “Silk Road of the Sea”, porcelain products were sold to countries along the Mediterranean coasts. Ming Dynasty navigator Zheng He led seven expeditions to the “Western Ocean”, visiting more than 30 countries along the way, including the Malay Peninsula and Vietnam, bringing to these countries large quantities of blue and white porcelain ware. Even today, countries of Southeast Asia have collections of fragmented porcelain pieces which they are loath to part with, and which are mounted with gold and hidden in secret chambers.

Today, many countries have museums that contain collections of these ancient Chinese porcelain items. For example, in the kitchen of Istanbul’s Topkapi Imperial Palace, there is a collection of close to a hundred blue and white porcelain items of the finest quality from Yuan Dynasty China. The blue and white porcelain vessels painstakingly created in the hands of Chinese craftsmen have survived the thrashings of long voyages and the devastation of wars, but they have never escaped from the eyes of their admirers.

Pieces of Chinese porcelain scattered along the coasts of the “Silk Road of the Sea” have shone upon the whole of Southeast Asia as well as African and Arab countries, like shining jewels.

National leaders of New China have often used fine Chinese porcelain ware as state gifts to foreign heads of state and friends. During the 1972 visit to China of former United States President Nixon, Premier Zhou presented him a precious set of blue and white porcelain dinnerware; in 1978, Deng Xiaoping gave then Japanese Prime Minister Fukuta a set of blue and white porcelain items of the study. Chinese Porcelain has built a bridge of exchange between East and West and embodies friendship among nations.

Light of times

The Palace Museum in Beijing, where imperial princes used to live, houses the world’s largest collection of ancient Chinese porcelain.

Geng Baochang, 88 years old, has worked at the Ancient Artifacts Department of the Palace Museum for almost 50 years. Throughout all these years, his most important daily work has been appraising and researching porcelain items. Mr. Geng says that he is most proud of his eyes, whose penetrating insight is a result of a long career of appraising ancient artifacts that started when he was 15 years old. Almost all the nearly 350 thousand porcelain items housed in the museum have passed through his appraising hands. Whenever an item comes to him, he will have it measured by an expert, have a brocade box custom-made into which he will put the item with the utmost care for fear of damage.“

Ancient Chinese porcelain is not renewable. When we are protecting the museum collection, we are actually also protecting our history and culture.” Ancient porcelain is not renewable. However, porcelain design and manufacturing are a lively reflection of changes of the times. In 1950s and 1960s, waves of porcelain enthusiasts from Japan and Europe visited Jingdezhen in order to learn the craft. Influenced by the industrial revolution in Europe, they brought many innovations to porcelain making, incorporating a lot of modern elements. In today’s Jingdezhen, you can see the ancient process of porcelain making as well as pieces of porcelain art, such as Franz porcelain, embodying design concepts of the Modern West. In Europe, Japan, Korea … dazzling arrays of porcelain ware have entered thousands of homes. Impearl Blue, the well-known British porcelain brand, is famous for its meticulous designs. Its blue and white Chinese porcelain patterns are said to be creatively based on the porcelain of Jingdezhen. In America, the Mikasa brand is also very popular, and many homes have a piece or two. During Christmas season, Mikasa sends promotional ads to its customers via newspaper and mail, and stores are flooded with bargain hunters. Mr. Liu Yuanchang, Director of Jingdezhen Ceramic Art Museum, has mixed feelings about all this: “Porcelain has spread from China to the whole world, and porcelain culture has evolved into a cultural industry. Now China has a lot to learn from the West in design and technology …”

The mellow hues of the glaze, the fluent movements of the painting brush … this thousand-year-old craft has been forged in the kiln of time and condensed into something more than an aesthetic pleasure. Below the jade-like beauty of its surface are sentiments condensed in the glaze pigments as well as history soaked into the body, all there to remind us of a heritage that has always been with us.

The civilization carved in Chinese porcelain is always with us. Flourishing for more than a thousand years, it is a treasure that belongs to all humanity.

Published in Confucius Institute Magazine

Published in Confucius Institute MagazineMagazine 14. Volume 3. May 2011.

View/Download the print issue in PDF

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario