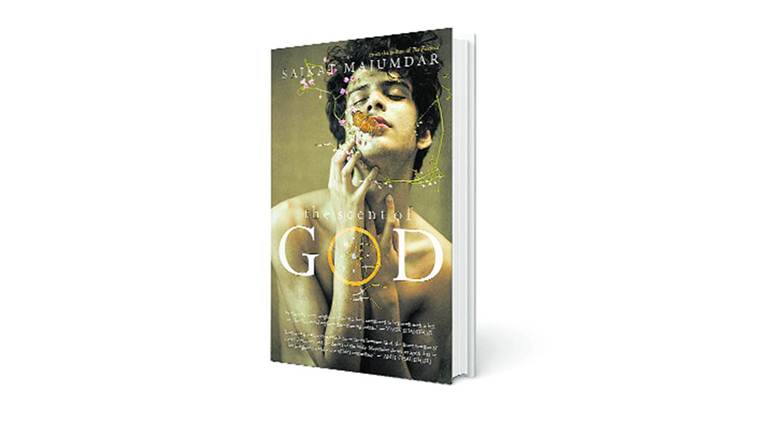

Written by Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar |Published: February 23, 2019 10:06:24 pm

Love Off-Campus

Despite events and anecdotes being only hinted at, the reader can adequately imagine and understand the taboos and secrets the author has not exactly put in words.

The plot is set in the early 1990s somewhere in the outskirts of Calcutta, in an all-boys residential school run by the monks of a Hindu monastic organisation who are dressed in saffron. The two lead characters are Anirvan and Kajol, students in the same class, who fall in love with one another in a place that “does not recognise their kind of love”. The next important character is Kamal Swami, a senior and much-respected monk who “was always right” and who “scared the boys a little”. Then there is Sushant Kane, the Class VII English teacher and debate coach, who “looked so hip that it was absurd”, who “belonged to the ashram…[and] yet…did not belong [there].”

In a novel like this in which things are mostly implied and not stated openly — where even a popular figure from India’s history is not named and only described as “an anti-British nationalist who became a friend of Hitler, who had asked young people for their blood so that he could give them freedom” — one question that comes to mind immediately upon reading this novel is: how much and what all do Swami and Kane know? Anirvan and Kajol are hiding things, while Swami and Kane are apparently helping them, for they seem to understand the relationship between Anirvan and Kajol. Be it asking Anirvan and Kajol to stay in each other’s company or harnessing Kajol’s aptitude in academics and Anirvan’s in oratory, Swami and Kane come across as two silently benevolent characters. Despite events and anecdotes being only hinted at, the reader can adequately imagine and understand the taboos and secrets the author has not exactly put in words.

The school — called “ashram”, or a monastery — had, seemingly, an “endless campus, spread over eighty villages from the past.” One of the villages outside the campus was called Mosulgaon, inhabited mostly by Muslims. An ecosystem was created around the ashram. “The children in Mosulgaon didn’t go to school. They wandered into the ashram through the cracks in the wall and gathered dry leaves and bits of wood and thrown away plastic bottles and cookie tins the boys got from home and sneaked out with the loot.” And yet, there was a hatred between the inmates of the hostel and the villagers of Mosulgaon, and this hatred for the other ran both ways.

Majumdar’s description of the life of privation led by the students in the ashram is atmospheric. Even fans were a luxury in the ashram hostel, so when the students returned after spending the summer vacations at their homes, they “chatted dreamily about the different kinds of fans they had seen that vacation.”

Despite the life of privation, most of the students — because they came from well-to-do, privileged households — had a strong sense of entitlement, so much that when they were denied TV, they “[threw] plates and plates of rice down the gutters behind the sink outside the dining hall”, more rice than the village of Mosulgaon had ever seen.

If the boys displayed entitlement, the monks displayed extreme masculinity as they devised violent methods to discipline the boys. At one point in the novel, the boys “stood frozen” at the door of the common room as they saw an unruly, big, muscular boy being “tossed around like a dry twig in a storm” by a monk with a “giant figure”. “[The monk] pulled [the boy] by his hair and hit him in a blinding flurry of flying saffron robes.” And somehow this violence was normalised, as apparently the boys subjected to it were the “dangerous kind”, “the ones who kicked Mission rules out of their way”.

These were the things that were seen and described in long passages. What were not described and were given only a terse, intriguing mention were “the monks [liking] the boys sweaty and breathless” and “soft and perfectly hairless”— things that remained unseen and, perhaps, unproven.

Along with Majumdar’s pointed commentary on the education system that are spread through the novel: “Being good at English grammar was a useless skill. It had nothing to do with real merit, which was about being good at physics, algebra or biology, real subjects that created success in life”, The Scent of God is a revelation draped in sensuousness.

Shekhar is the author of The Adivasi Will Not Dance

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario