There’s Space for Petty Gains

Veteran rocket engineer S Nambi Narayanan on being embroiled in the ISRO spy case along with six other colleagues and how the fictitious case set India's space programme back by years.

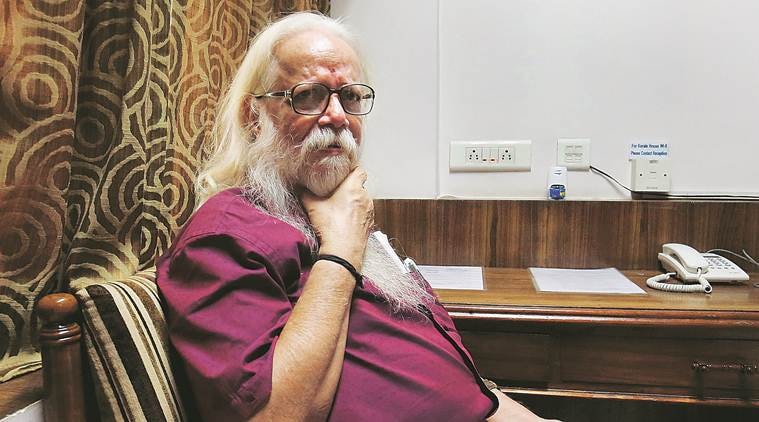

S Nambi Narayanan was a rocket scientist at Thiruvananthapuram’s Liquid Propulsion Systems Centre when the case against him and his colleagues unfolded in 1994. (Express photo by Anil Sharma)

Book: Ready to Fire: How India and I Survived the ISRO Spy Case

Author: Nambi Narayanan and Arun Ram

Publication: Bloomsbury

372 pages

Price: Rs 599

Author: Nambi Narayanan and Arun Ram

Publication: Bloomsbury

372 pages

Price: Rs 599

“One cannot develop a rocket by seeing how it is made, not even if given detailed drawings of all the systems. If that was the case, a small-scale industrialist doing a metal plating for a rocket part should be able to replicate the rocket since he, like any other contractor, is given the blueprint… A rocket cannot be made just with the know-how. You need the ‘know-why’.”

“Anyone with a basic understanding of rocket science knows even if the drawings are given, that an engine cannot be made without long years of development, guidance and extensive tests… If rockets were built merely with drawings, there is no reason why every space-faring nation is making rockets its own way and not copying from others.”

This argument makes multiple appearances in S Nambi Narayanan’s personal account of how he, a rocket engineer of considerable repute, became the central character in a fantastically fabricated story of espionage in which he was accused of passing on “secret” rocket designs and drawings to Pakistan through Maldivian conduits for considerations of sex and money. It is also an argument that sleuths of the Kerala Police or the Intelligence Bureau had scant regard for, and little understanding of, as they spun together a salaciously imaginative but dangerous plot in the winter of 1994, with active help from a sensation-hungry media and a divided political class in Kerala.

The ISRO spy case was comprehensively debunked by a subsequent CBI investigation that led to the acquittal, by the Supreme Court, of all the seven accused in 1998. Last week, the Supreme Court also ordered the Kerala government to pay Narayanan a compensation of Rs 50 lakh.

But immense damage had been done in the meanwhile. Narayanan writes that the case had pushed back India’s space programme, especially the development of the cryogenic engine, of which he was the project director, and which is crucial to the success of present-day and future rockets, by at least 15 years.

It all started with a Kerala police inspector arresting a Maldivian woman on charges of overstaying her visa. Her diary contained telephone numbers of D Sasikumar, a scientist, like Nambi Narayanan, at Thiruvananthapuram’s Liquid Propulsion Systems Centre. That is how the case got linked to ISRO. As events unfolded after that, several disparate elements discovered that this case could be used to push their own little agendas and settle personal scores.

A number of interests merged in this case: a local inspector miffed with a foreign woman in distress, after his sexual advances were rebuffed, a faction of the ruling party attempting to unseat the chief minister, a soon-to-retire intelligence officer hoping to sign off his high-profile career with a blockbuster case, another intelligence officer nursing a grouse against a space scientist for rejecting a candidate he had recommended for employment, a newspaper editor trying to settle scores with a senior IPS officer after losing a court battle against him in a private case, an IAS officer getting back at a scientist for having taunted him on his lack of technological expertise, and, above all, a foreign power keen to thwart or delay the emergence of competition in the international satellite launch vehicle market.

Eventually, the scandal became much bigger than the sum of these small petty games, but it was strung together by an increasingly shaky storyline and based on extremely thin or non-existent evidence. The case was bound to collapse on closer scrutiny. Narayanan is full of praise for the CBI for its professionalism and unsparing in his attack on MK Dhar, a celebrated joint director of the Intelligence Bureau, virtually accusing him of playing into the hands of American intelligence and being “loyal to his foreign masters”.

To buttress his point of Americans having infiltrated the top brass of the IB, Narayanan cites the case of Dhar’s colleague Rattan Sehgal, another joint director who was forced to quit after his links with American intelligence officers in Delhi were discovered. “It is strange that the ISRO spy case started a few months after Sehgal joined the IB from the Ministry of External Affairs, and ended around the same time he was chucked out of IB,” Narayanan writes.

It is worthwhile to go back to Dhar’s account of the ISRO spy case in his book Open Secrets: India’s Intelligence Unveiled, which appeared in 2005, well after the Supreme Court had trashed the case. Dhar remained convinced of an espionage angle. He blames the CBI for hushing up the case under political pressure. This, he claims, happened because his boss, then Director of Intelligence Bureau, DC Pathak, in his eagerness to impress his political masters, kept sending raw updates, including unverified leads, to the government. One update contained a reference to Prabhakar Rao, the son of then prime minister PV Narasimha Rao. Dhar, who died in 2012, claimed that after this, the entire effort of the top political establishment was to somehow close the probe. In his book, Dhar listed unanswered questions in CBI investigations, many of which are dealt with in Narayanan’s book.

Narayanan’s book is also extremely readable for a different reason. The ISRO spy case, in fact, forms barely one-sixth of this book. The rest is a fascinating history of the development of liquid propulsion technology. Narayanan, an early and strong proponent of liquid fuel engines in ISRO, provides a detailed account of how he, and 100 other ISRO scientists, toiled at a French facility for five years to master a technology that, finally, after a 15-year-effort, culminated in the development of the Vikas engine that powers the PSLV and GSLV rockets. Personal experience in developing a rocket engine from scratch gives Narayanan the conviction to repeatedly proclaim in the book that rocket development was not merely a question of knowing the right design, and that the technology could not just be passed on in a few pieces of paper.

There are barely half a dozen books about ISRO’s remarkable journey. Nambi Narayanan’s book, though written in a completely different context, has been a valuable addition.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario