Written by Sanjay Sipahimalani |Updated: February 2, 2019 2:40:30 am

Darkest Hour

An inventory of observations stockpiled over many years of viewing the classic — Where Eagles Dare.

Steven Spielberg once called it his favourite war movie. For the fastidious New Yorker critic Anthony Lane, it’s “a work of art I revisit with the devout regularity that others reserve for the shrines of saints.” The Australian writer Clive James watches “every re-run on television in order to reinforce my stock of telling detail — and, all right, in order to have a wonderful time.” Even Michael Ondaatje is a fan. Where Eagles Dare, directed by Brian Hutton and first released 50 years ago, still has its share of devotees despite, or perhaps because of, its boy’s-own-adventure shenanigans.

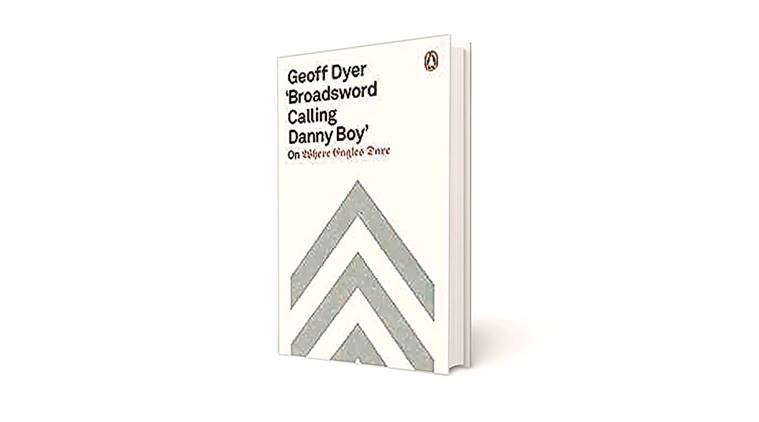

This is the World War II thriller that Geoff Dyer takes as the subject of his second book on film — the first being Zona (2012), on Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), a very different beast. Where Eagles Dare, however, was one of the defining films of Dyer’s childhood. In a comment that many will nostalgically agree with, he writes that it “still seems…to contain some essence of what cinema means to me now, when action movies have become a form of explosive torpor.” His slim Broadsword Calling Danny Boy is an inventory of observations, from the caustic to the enthusiastic, stockpiled over many years and viewings.

The saga, based on a script that Alistair MacLean wrote in six weeks — the novel came later — deals with the derring-do of army officers, played by a world-weary Richard Burton and assisted by a taciturn Clint Eastwood, who parachute with their team into Schloss Adler, an Austrian fortress, to rescue an American brigadier-general captured by the Nazis. The title of Dyer’s book is, of course, Richard Burton’s oft-repeated code phrase in the movie, still beloved of by the actor’s fans and impressionists.

Soon enough, it turns out that the mission is murkier than it appears: there are wheels within wheels involving British agents, German agents, and double agents, with as many twists and turns than within the corridors of the fortress itself. Towards the end, Burton tells his team that they have to create confusion so that they can get out of there alive. Eastwood’s wry reply: “Major, right now you got me as confused as I ever hope to be.”

Dyer takes an almost shot-by-shot approach to the material, commenting on scenes as they progressively unfold. Of course, being Dyer, he manages to incorporate an array of cultural reference points, from war correspondent Martha Gellhorn, to artist Piotr Uklanski, to poet Rainer Maria Rilke, to writer Svetlana Alexeivich, to, not least, his stylistic guru, Thomas Bernhard.

Along the way, there are plenty of quips and humorous asides — though “asides” would be a wrong way to look at it, because the drollery is often inextricable to Dyer’s modus operandi. He makes much of Burton’s hungover appearance, as well as Eastwood’s facial range; at one point, Dyer says, “he’s not just squinting, he’s squinting in German.” And on their “apparently bottomless” rucksacks, he comments: “They have not packed lightly, these two; they have enough clothes and equipment to keep the Sherpas on an inter-war Everest expedition employed for much of the climbing season.”

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario