Written by Ram Sarangan |Updated: February 2, 2019 2:30:20 am

Sweet Young Things

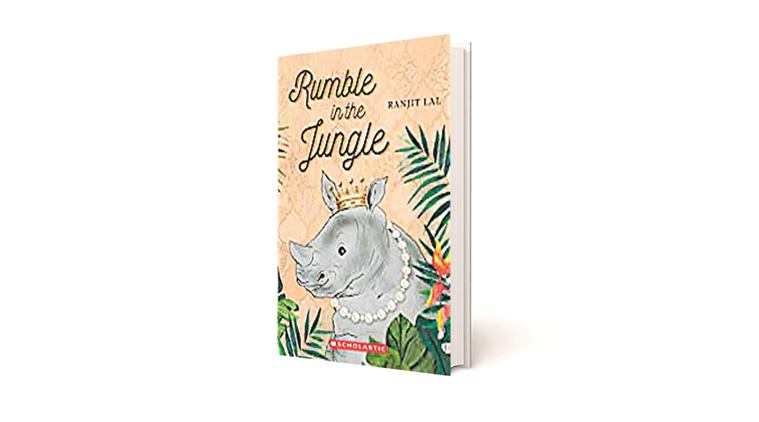

An irreverent if slightly predictable story on the problems that the young of every species face.

There are no animals in Rumble in the Jungle, only humans. At least, this is the conclusion when looking at Ranjit Lal’s humorous, colourful book in which humans and rhinos, aside from their obvious biological differences, are portrayed to have the same kinds of fun, the same varieties of problems — and, of course, the same types of “villainous villains”.

Prince Shamsher Bahadur Rana Thakursingh is the 12-year-old scion of the former royal house of Gaindagunj. Sick of the boarding school his parents have packed him off to, he uses the chance while back home on a break to carry out an ancient ritual to “save his father’s degenerate soul”. That this tarpan ritual involves crawling into the stomach of a dead rhino only seems to heighten his enthusiasm, in the way 12-year-olds are heard saying “cool” when hearing descriptions of gore.

It is during this vacation that Shamsher meets Teesta, the nine-year-old adopted daughter of the head of the Special Rhino Protection Group (SRPG), who upstages every child with a pony by riding a young rhinoceros instead. The SRPG protects the former royal family’s hunting ground-turned-national park, where Teesta finds and rescues Roly-Poly, a young female rhino who is then taken to a human home to recover from her ordeal.

Roly-Poly is somewhat of a persona non grata among others of her species, especially the equally young Rumble-Tumble and his mother Gaindaben, as she has become far too close to humans. Rumble-Tumble, who is prohibited from playing with Roly-Poly by his overly doting mother, naturally does the exact opposite by trying to meet her at every opportunity. This sets the stage for the chaos that both sets of children leave in their wake for the rest of the book.

Lal’s flair for humour is evident and it complements the nonsensical nature of the story perfectly. The book is rife with tropes that one normally associates with such works for children — wild children who are irreverent of customs or biases imposed on them by adults, anthropomorphised animals and caricature villains. This is both good and bad; the book is executed well enough that things stay light, funny and action-packed, with plenty of mud baths for children of all species. And, of course, many of these themes become tropes exactly because they work so well. However, this also makes the book a little predictable. The idea of anthropomorphised animals in a book which also has an equally large human cast is a little odd, as it eventually winds up being two helpings of the same thing.

However, any problems with the book are largely offset by the ingredients that make up its style and theme — a lot of borderline satire, and just inappropriate enough for one to question if their own young mind should be allowed to read it.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario