Written by Dipanita Nath |Updated: February 8, 2019 8:57:54 am

Probir Guha’s adaptation of Titas Ekti Nodir Naam focuses on when the river can give no more

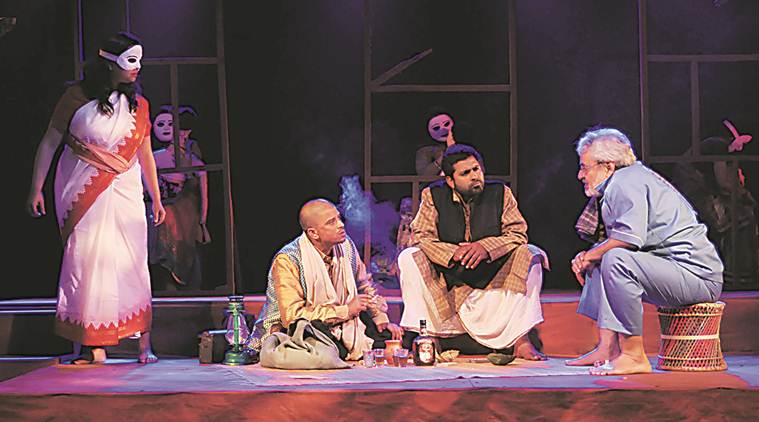

Titas Ekti Nodir Naam, based on a novel by Adwaita Mallabarman and immortalised by filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak, drew a largely Bengali audience at Shri Ram Centre and, gently, touched the raw nerve of migration among an audience that had forgotten they were migrants.

As the house-lights came on after Probir Guha’s play at Bharat Rang Mahotsav on Tuesday, many people hastily wiped their wet eyes. Titas Ekti Nodir Naam, based on a novel by Adwaita Mallabarman and immortalised by filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak, drew a largely Bengali audience at Shri Ram Centre and, gently, touched the raw nerve of migration among an audience that had forgotten they were migrants.

Several years ago, in a village in West Bengal, Guha had asked audiences to keep their eyes closed during an hour-long show that was based on the Best Bakery case. “By shutting out sight, we wanted to create a play that would appeal to the other four senses, from touch to smell,” he says. He recalls that people fainted during the show and one critic commented, “Theatre you can’t see is more powerful than theatre you can.”

This ability to evoke elemental emotions through a form of theatre that is both physical and psychological, is one of the reasons Guha is considered a living legend from Bengal. “Right from the beginning, my aspiration was that I must make theatre that would go close to people,” he says.

Titas Ekti Nodir Naam is set in a fishing community on the banks of the Titas river in Bangladesh, and follows the fates of a young man, his bride, who is kidnapped immediately after their marriage, and a woman who used to love him dearly. Guha’s adaptation focuses on when the river can give no more and people must seek their livelihood far from its soil. The men and women, who have lived around water for generations, must now teach their minds and bodies the work of the land, such as labouring at construction sites and in farms. “This play matches our ideology. We work with the marginalised, most of who are people who have migrated. I am also a migrant and I know where it hurts,” says Guha.

Born in 1948, Guha came to West Bengal when he was four. Back in Khulna, Bangaldesh, his father used to be a teacher. In West Bengal, he was jobless until he found employment as a police constable. “My father was a seedha-saadha, village man. After he got the job, he began to be posted all over the state,” says Guha. When he was a little older, his father was transferred to a remote area of Murshidabad, “dominated by people who many of us call neech jaat”. “These people became my friends and it was with them that I would run and play. I understood sorrow, pain and frustrations of the disenfranchised. I decided that I would do something for them one day,” says Guha.

Guha’s first vehicle of change was politics. He was an active member of the undivided communist party and then joined the CPI(M). “The party told me, ‘You gather some boys and organise plays and music performances because elections are coming’. I did that and that’s when I realised theatre has the power to say something.”

Guha’s first vehicle of change was politics. He was an active member of the undivided communist party and then joined the CPI(M). “The party told me, ‘You gather some boys and organise plays and music performances because elections are coming’. I did that and that’s when I realised theatre has the power to say something.”

After quitting politics, he came into theatre, driven by a desire to be heard. He worked with Badal Sircar, Peter Brook, Jerzy Grotowski and Richard Schechner but “my heart wasn’t in it”. He appeared in several proscenium plays in Kolkata before declaring that the city of connoisseurs was not for him. “This was intellectual urban theatre. I decided to look back at theatre in Bengal that was thousands of years old. Why should I adopt European theatre when I had my rich tradition?” he says. He began to study rituals, traditions, languages and songs of Bengal and worked with folk practitioners in India and other countries.

His group, Alternative Living Theatre, was born in 1977, and finds performers among small traders and farm hands to labourers. While other groups begin plays with a script, Guha starts with conversations with his actors. He isn’t a writer but assiduously makes notes of these conversations, from which emerge his plays. “We have less text, more physical actions and this, I think, makes a psychological impact on the audience. It was a journalist and not me who coined the term psychophysical theatre for our work,” says Guha. His experiments includes Third War, in gibberish, which travelled through India and Japan. Another well-known play, Abdul Hannan ki Maut, revolves around the death in the minority community. “The protagonist dies four times — in a riot, during Partition, at the Gaza Strip and, finally, confronts the Almighty to ask, ‘Why should I die repeatedly because I belong to a certain community?’” says Guha. Another play, Victimised, dealing with the persecution of the minorities, was performed in Lahore, among other places.

In Titas Ekti Nodir Naam, Guha keeps sets simple and the costume ordinary, but accompanies the action with the live music of the fishing community. “The fun of this play is in its simplicity,” he says, aware that loss of a homeland is always measured by absence of simplicity.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario