Written by Ektaa Malik |Updated: February 22, 2019 10:48:55 am

Veteran Australian photographer John Gollings on capturing architecture marvels, the frailty of modern design and his love for India

The exhibit is a sort of a time capsule of architecture, beginning at least 20,000 years ago with the rock paintings of Nawarla Gabarnmang in Northern Territory, Australia, to the more modern Burj Khalifa, Dubai.

Angkor Vat, Cambodia; Pushkarni Kund, India; Kabaw Berber Granary, Libya; Holocaust Tower, Germany; Sydney Opera House, Australia — this may look like the beginning of a well-thought out travel bucket list. For veteran Australian photographer, John Gollings, these are memories of a lifetime — images captured in a career spanning more than five decades. These works and more constitute ‘The History of the Built World’, a travelling exhibition from Monash Gallery of Art, which is currently being showcased at India Habitat Centre’s biennial photo festival, Habitat Photosphere.

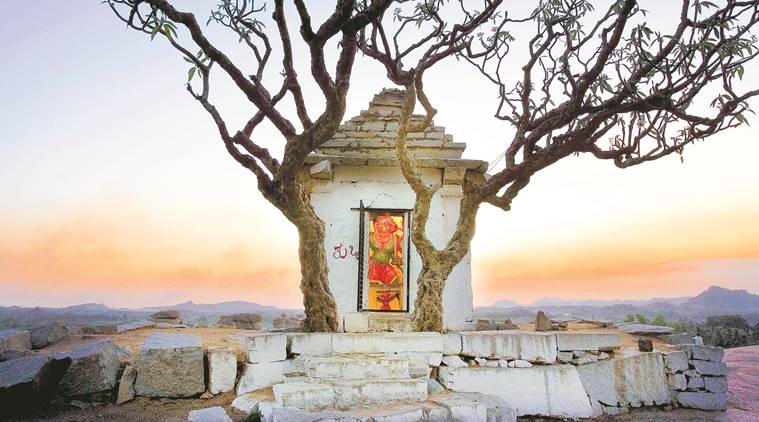

The exhibit is a sort of a time capsule of architecture, beginning at least 20,000 years ago with the rock paintings of Nawarla Gabarnmang in Northern Territory, Australia, to the more modern Burj Khalifa, Dubai. He was photographing some cathedral rock art, when he found a lingam in the ceremonial ground. “It confirmed my notion that the Australian Aboriginal is the Dravidian Indian, who came to Australia 60,000 years ago. It’s the first confirmation, as there wouldn’t have been a linga without some influence of Hinduism. That’s been carbon dated at 30,000 years. It’s the only instance of the Aboriginals building things by taking out columns and manipulating the structure, obviously using their Indian stone making skills,” says Gollings, as he elaborates on the rock art photos on display and his initial association with India. “I visited in 1980 to photograph Hampi, and I have come back every year. I fell in love with the place. Though curiously, ever since it’s become a world heritage sight, it’s been more and more difficult to work there. There are fences in place, and it shuts at five,” says Gollings.

India and Hampi feature prominently in the exhibition which has 67 photos. His recent project is about photographing all the step wells of India. So far, he has documented 125 of them. “My effort has always been to make a building stand out. I wish to take the single most iconic picture of the said monument. Early on, when you photographed Indian temples, on black and white film, the colours of the stone and the blue sky would all be of the same density. You got this muddy look, so I started photographing at night, to make the colours stand out. I used my work in India to photograph modern architecture,” he says.

Gollings is a self-taught photographer, who fell in love with photography when he was only nine. He progressed to the dark room at 11. Post learning the ropes of the artform, he straddled the world of glamour and tried his hand on fashion and advertising photography before embarking on this anthropological study and documentation of architecture. “I studied architecture at Melbourne University. Advertising was a chance thing. I was asked to assist Norman Parkinson’s assistant, the famous London photographer. I picked up some very big accounts, but as my contemporaries from architectural school were making buildings, I became their go-to photographer,” says Gollings. By the mid-70s, he was doing equal amounts of fashion and architectural photography. “I realised that no one wants a 12-month-old fashion photo, as it’s out of date, but they want pictures of buildings. And that’s when an epiphany occurred. My hobby of photographing dead cities had a link to my whole career, which was to photograph everything that had ever been built in the world,” says Gollings.

Having seen the world grow and expand from rock cut caves to plate-glass facades, Gollings is full of caution, especially where the new glitzy, bold buildings are concerned. “We create one structure, and then we get bored of it. So we decorate. From the Roman style, we got to Baroque, then we moved to Modernism, where we had white boxes. And now we are looking at curvaceous architecture, which is only possible with computers. I think it’s all a bit silly. One is a stylistic development, and the other is a mechanical one. And at the same time, the buildings are more fragile. A modern office building is designed to last 25 years, compared to the great monuments of India, which have been here for centuries. They are stone buildings. Even concrete corrodes and collapses. There won’t be anything left of modern civilisation. It’s a fascinating conundrum,” adds Gollings.

The sombre tone and words of caution continue as he stresses on the photos of the Kabaw Berber Granary, Libya, and Angkor Wat. The majestic temple complex (Angkor Wat) is now a pale shadow of what it once was. “While photographing these ‘dead cities’ — I have been told to not call them that — or ‘lost civilisations’, I have realised that one way or the other, we are all heading there. Various big civilisations were run aground because of climate/political/catastrophic reasons. Climate change is a reality. It’s the one solitary lesson from history that people like Donald Trump are not ready to take. Nothing lasts forever, except the remnants of architecture built from stone. All this modern stuff, it’s going to fall,” concludes Gollings.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario