Ballad of Ayesha Book review: A Land Remembered

A blend of the mythical and political gives this Bangladeshi novel in translation its special significance

Written by Purabi Panwar | Updated: September 15, 2018 1:15:13 am

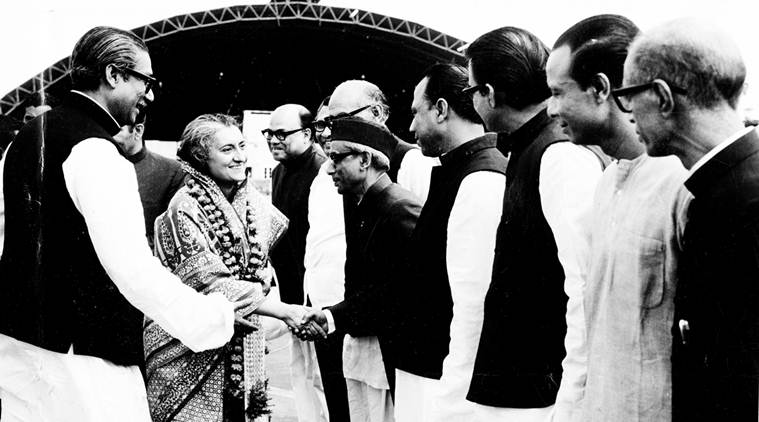

Sheikh Mujibur Rehman introducing Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to members of his cabinet in March, 1972. (Express Archive)

Anyone reading The Ballad of Ayesha by Anisul Hoque (Ayesahamangal in the original Bangla) would enjoy the book more if two things are kept in mind. The folk myth of Manashamangal — the story of Manasha the snake goddess and her encounter with Chand Saudagar, his sons and most importantly his daughter-in-law Behula who brings her husband Lakhinder back to life through her devotion, is a story that cuts across the border and is very popular both in rural Bengal and its counterpart in Bangladesh (both snake infested areas and one must not forget that Manasha is the snake goddess). Another major context of the novel under review is the coup in Bangladesh in 1977 with the overthrow and assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rehman and his family. Many soldiers and officers of the Bangladesh Air Force were arrested and hanged and no one knew of their fate until 1997 when Zayadul Ahsan a reporter of the Bangla daily, Bhorer Kagoj, ran a series of stories about the coup and its aftermath.

It is this context, the blend of the mythical and the political, that gives The Ballad of Ayesha its special significance. The novel opens with a letter received by Ayesha that her husband Corporal Joynal Abedin has been sentenced to death for “…an attempted coup in the defence force on 2 October 1977.” Another packet containing the clothes he had been wearing and a small sum of money is delivered by the postman. Ayesha’s world is shattered. With no income and two small children to bring up, her future seems bleak.

But her resilience seems remarkable. The way in which she establishes herself and manages to eke out a living, using her education, to attain a degree of financial independence, shows a grit and determination that is no less than Behula’s. No, she does not manage to reclaim her husband from death, that sort of thing does not happen in real life. But the tragedy makes her strong and capable so that she is able to cope better and come to terms with her personal loss. One does not see the tears behind the veil, her grief is somethig very private. This reviewer feels that she is the modern day Behula, not able to bring her husband back to life, but determined to visit his graveyard on his death anniversary (though the graves are not marked), and, maybe, observe some rituals as a mark of respect to her late husband. Somehow, one remembers the scene in Vishal Bhardwaj’s Haider, when the protagonist finally finds the grave of his father who had been reported missing for quite some time and offers his prayers there.

Ayesha’s story is not just the story of a woman’s loss and grief. It brings out a dark period in the history of Bangladesh when attempts had been made to destroy everything that Mujibur Rehman had stood and fought for. In the conversation with the translator Inam Ahmed, Hoque says that he had been at the university at that time when the country was ruled by the Army and joined the movement demanding democracy like everyone else. To quote, “I wrote for democracy. I thought one way of reclaiming democracy was through literature.”

A look at literature from Latin American countries where military dictators went all the way to gag voices of dissent substantiates this. Literary devices like magic realism, blend of myth and reality and others were used to bring attention to the dark reality but in an oblique way so that it was beyond the comprehension of the dictator. Looking at The Ballad of Ayesha, in the larger context, one feels that this is what Hoque intended by bringing in the story of Behula and blending it with the events in Ayesha’s life. The semi-mythical context takes it beyond the local which, on one hand, generalises its appeal, and, on the other, would save it from being censored, if such a situation arose. In conclusion, one must praise the quality of translation. Ahmed has presented not just a story but a socio-cultural ambience and most importantly, a politically turbulent period in a language that has only recently lost its “foreign” tag.

Purabi Panwar is a writer and translator based in Delhi

.png)

The Ballad of Ayesha by Anisul Hoque (Translated into English by Inam Ahmed)

The Ballad of Ayesha by Anisul Hoque (Translated into English by Inam Ahmed)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario