Treasured Epistles Book review: Between Friends

An enduring collection of correspondence between K Natwar Singh and his eclectic circle of friends that included Nirad C Chaudhuri, Indira Gandhi, RK Narayan and Mulk Raj Anand

K Natwar Singh (sitting, right) with Turkish foreign minister Mesut Yilmaz in Ankara, Turkey in July, 1988. PM Rajiv Gandhi is in the background. (Express Archives)

Some people collect postage stamps. They stick them in an album. Others collect celebrity letters. They, then, archive the yellowing epistles before publishing a carefully chosen selection. The printed record is more long-lasting than the ephemera of Twitter and Facebook. In the 21st century, the ubiquitous resort to email has all but killed the noble art of letter-writing. We are left with, “hi, tx, c u”. Is this English? So, those who have preserved and printed thoughtfully crafted communications from names that still resonate in our collective memory deserve our grateful thanks. Kunwar Natwar Singh surely ranks among the peers of this dying tradition.

His latest offering, Treasured Epistles, reflects his large and eclectic circle of friends, all of whom have passed away but only after leaving “their footprints on the sands of time”: statespersons of the order of Indira Gandhi and C Rajagopalachari; masters of literature like EM Forster, Han Suyin, Nirad Chaudhuri, RK Narayan and Mulk Raj Anand. I don’t quite know where to categorise Lord Louis Mountbatten — among the mountebanks and charlatans or those who made history (badly)? Indira Gandhi has this to say about Mountbatten in a letter dated January 4, 1975: “Lord Louis is, as you know, incorrigible. He is friends with all the wrong people and presumably believes what they tell him about me and about India”.

Natwar’s correspondents in this selection include Nehru’s two sisters, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit and Krishna Hutheesingh, who hated each other, which comes through wickedly in the correspondence. For example, there’s this letter from Krishna to Natwar dated August 12, 1960: “My sister has played another foul trick on me and stabbed me in the back…(I) am going to have it out once and for all with PM” (their common brother)!

Natwar’s guru, EM Forster, figures largely in the correspondence. Much of it is fulsome praise but the best bits are the waspish stings. Thus, Forster writes to Natwar of his first meeting with Nirad Chaudhuri in June 1955: “I liked Mr. Chaudhuri — thought him so first hand and it was remarkable how much and how genuinely he was enjoying English 18th century homes”. Nirad Chaudhuri would have nothing to do with such well-meant if patronising comments. In a letter to Natwar after Forster had written a rather negative review of Niradbabu’s A Passage to England (1959), he hits out at Forster: “He aired condescension towards me, which showed what a fool he was” and goes on to list “howlers” in A Passage to India (1924), which had established Forster’s reputation three decades earlier: “He made a Shudra the brother-in-law of a Brahmin and gave the name of Amrit Rao to a Bangali barrister from Calcutta.”

To Natwar’s horror, Nirad C went onto say, “EM Forster would not be allowed to enter his house”. Mulk Raj Anand is indignant at this: “Such vulgarity of the dissenter Chaudhuri, was unworthy of an Indian”. It is a tribute to Natwar’s liberal spirit in these illiberal times that he includes all this in his selection — warts and all. For, as Mulk Raj Anand admonished Natwar in a letter dated August 13, 1963, “To do homage to genius one must also record the failings of a genius, without viciousness and anger.”

Rajaji also expresses his disapproval of this British liberal who holds that the only mistake of the Imperial regime was “the arrogance of the officials”. He goes on: “In Forster’s book, the Englishman and woman come off best, the Musulman next best. The Hindu who is really detested — his social customs and his religious practices — all included, comes off worst.” Forster, Rajaji felt, was sure that “without the Englishman, India under the Hindus will go to rack and ruin”. CR then adds wryly (and we can see in the punchline where Gopu Gandhi comes from): “Perhaps it has proved true!” Natwar adds a footnote: “Here I don’t agree with Rajaji. His understanding of Forster’s writing was flawed.” Begging Natwar’s pardon, I think Rajaji was dead right!

Ved Mehta, the “blind writer” with a keen eye for the salacious, figures in several of the sharper comments of the correspondents. Rajaji wrote to Natwar in 1966 of the “comprehensive questions” Mehta had readied for his interview, “all based on the calumnies he had collected in advance”. In a subsequent letter, CR adds: “I had feared I was guilty of an unfavourable prejudice, but your letter has cleared my conscience”. Chaudhuri had no such reticence. Explaining why he had turned down a lucrative offer from the New York Review of Books to review Mehta’s latest book, he patiently explains to Natwar that as Mehta was blind, “that book could not be authentic”, but tells the editor “that since VM had spread calumnies (all falsehoods) about me in his book, people might misunderstand me.” Of Mehta’s preoccupation with Mahatma Gandhi’s “sexual obsession”, he wonders how “a potboiler writing for an American public — and a Punjabi at that”, could possibly understand anything about “G’s sexuality” or, indeed, “Hindu sensuality” which is a “brand” of its own.

In the battle of the litterateurs, Mulk Raj Anand weighs in with this about fellow-writer Shanta Rau: “Please tell Shanta not to despise me as much as she does”, adding, “In literary criticism, a battle of ideas is permissible, but not mere dismissal of an old writer and a phrase.” That, however does not stop Anand from going after Khushwant Singh, for whom Indira Gandhi had forced the veteran M Chalapathi Rau from the editor’s chair at the National Herald: “Madame seems to have discarded the old loyal Nehruite for this skunk merely because he turned chamcha to Sanjay Gandhi and Maneka.”

And I serve up here as dessert, Indira Gandhi’s assessment of Natwar’s report from London that Subramanian Swamy was “being welcomed in England.” She tartly adds, “His sort would be!” And goes on to say, “In India he has no influence whatsoever even in his own Party. He has not been a success in Parliament and there are often sniggers when he gets up”.

A real fun read that leaves more serious reverberations resounding in the mind, I commend it for your bedside table.

The writer is a former minister of the Congress Party

The writer is a former minister of the Congress Party

.png)

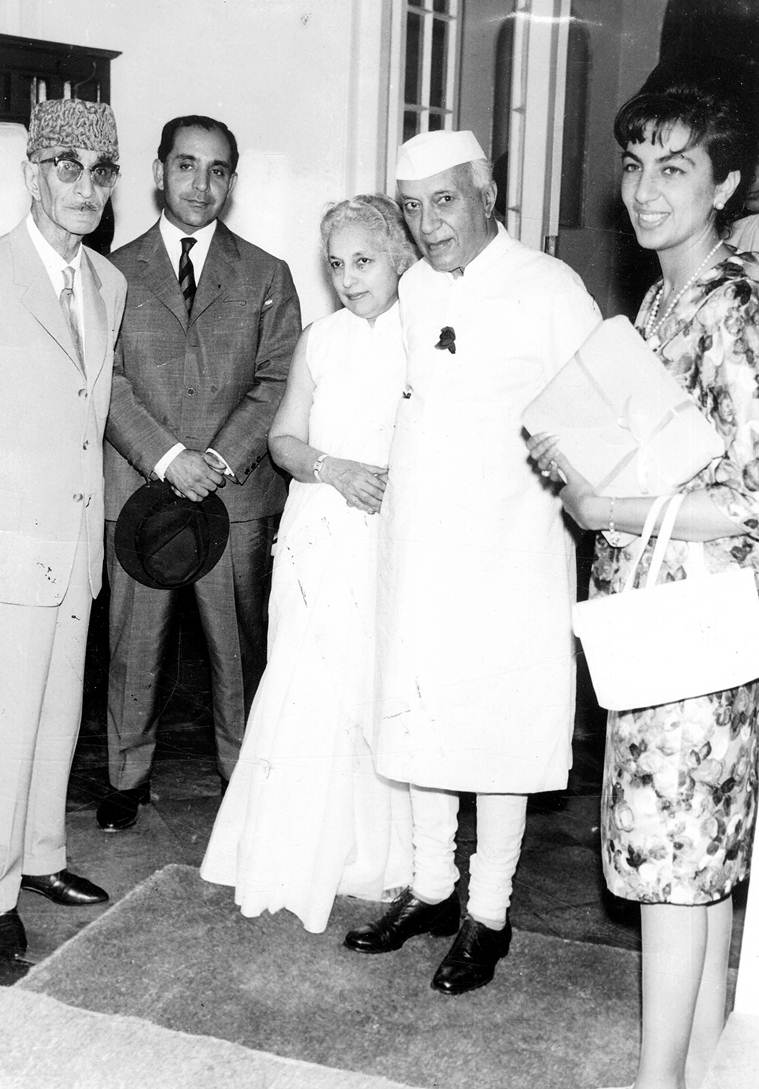

Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit (in white) with her brother

Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit (in white) with her brother  TREASURED EPISTLES by K. NATWAR SINGH

TREASURED EPISTLES by K. NATWAR SINGH

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario