Written by Vikram Chaudhary |Published: March 23, 2019 12:45:07 am

Return of the legend

Retracing the journey of two Parsi gentlemen to Czechoslovakia in the late 1940s, from where they brought back a motorcycle, and, a legend

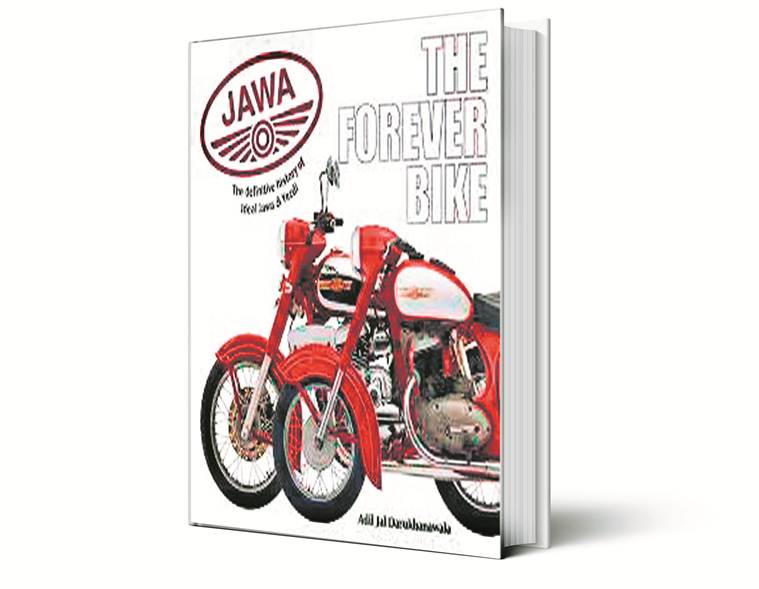

Book: Jawa: The Forever Bike: A Definitive History of Ideal Jawa and Yezdi

Writer: Adil Jal Darukhanawala

Publication: DJ Media

Page: 286 pages

Price: Rs 4,500

Probably the most famous photograph of a man fence-jumping on a motorcycle is that of Steve McQueen in The Great Escape (on the Triumph TR6 Trophy). But show it to any grown-up daddy cool — the author describes the breed as the one that rode Jawas and Yezdis during 1960s-1980s — and the likely answer would be: “Been there, done that.”

Jawa was a Czech brand, brought to India by Farrokh K Irani and Rustom S Irani. The Indianisation of the Jawa brand, built to greater standards of ruggedness, resulted in the Yezdi. The sporty nature of these motorcycles and their nimble handling created a cult following; they were cool, quick and easy to maintain. In Jawa: The Forever Bike, Adil Jal Darukhanawala — journalist, author and a motorcycling genius — describes not only how these Czech machines came to India, but also how they became Everyman’s dream bike and how the brand got resurrected.

The book reads like a historical account of a modern, getting-industrialised India. The first four chapters describe not only the journey the two Parsi gentlemen (Irani and Irani) made to Czechoslovakia in 1949 to bring the Jawa to India, but also how the country lacked a two-wheeler manufacturing ecosystem and so it was a field wide open. Moreover, Indians needed cheap mobility solutions, and for companies such as Bajaj Auto (that tied up with Piaggio of Italy), Automobile Products of India (that brought the Lambretta to India) and Madras Motors (that started assembling the British Royal Enfield), there was no place better to look at than war-ravaged Europe — which was developing similar solutions for its people and had the technology.

An aside — the Iranis had an agency by the name of Ideal Motors in Bombay and used to import BMW and Sunbeam motorcycles in small numbers; they made the trip to Europe because they wanted to be bigger players rather than mere importers. They started by becoming distributors of CZ (also a Czech brand) and Jawa, and manufacturing followed.

Chapters 5-24 are all things Jawa and Yezdi — how Ideal Motors transitioned to Ideal Jawa India Ltd (with help from the Maharaja of Mysore) and then to Yezdi (there is an interesting story how the name was arrived at), and, finally, how it all ended for Ideal Jawa in 1996 when the company shut operations; rising oil prices, new emission norms and the wave of Indo-Japanese bikes killed it.

Because it’s a coffee-table book, the text is interspersed with some rare photos of the times — including that of BS Shinde, one of the longest-serving employees, doing a Steve McQueen on a Yezdi — and these give you an honest picture about the Indian motorcycle industry. There is also enough data to make for an analyst research report; for instance, the sales data of the entire Indian motorcycle industry from 1955-96. For Jawa and Yezdi enthusiasts, there is detailed description of all the models sold and made in India, as also the company’s exploits in the field of racing.

As you turn the pages, it starts growing on you how Jawa and Yezdi turned into iconic brands, how they introduced young Indians to the concept of motorcycle touring, why Jawa and Yezdi clubs are still alive and breathing, and why they were sport, not just transport. The brand is still spectacularly popular, and I can vouch for it. In December, during the first media experiential ride of the new-age Jawas from Udaipur to Kumbhalgarh (about 100 km) in Rajasthan, I was stopped four times by people aged roughly 25-65 (one shopkeeper, one tea vendor, one man driving an Audi, and a tourist guide); their common expression was “The Jawa is back!” This brand indeed transcends time and societal barriers.

The last few pages are about the rebirth of the brand. How Anand Mahindra (a man everyone knows) met the zestful Anupam Thareja (founder of Phi Capital, and what I know of him after two brief meetings — a passionate rider) over lunch and Jawa was reborn. The new company, called Classic Legends, aims to revive dormant brands; Jawa is the first, followed by BSA (the British company).

The 21st century India needs more such books, not only because these are rare and so make for an informative read (no one has penned anything as definitive on the history of an Indian automotive brand before Darukhanawala), but also because they celebrate the arrival of Indian manufacturing and economic prowess.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario