Written by Pooja Pillai |Updated: March 7, 2019 8:23:37 am

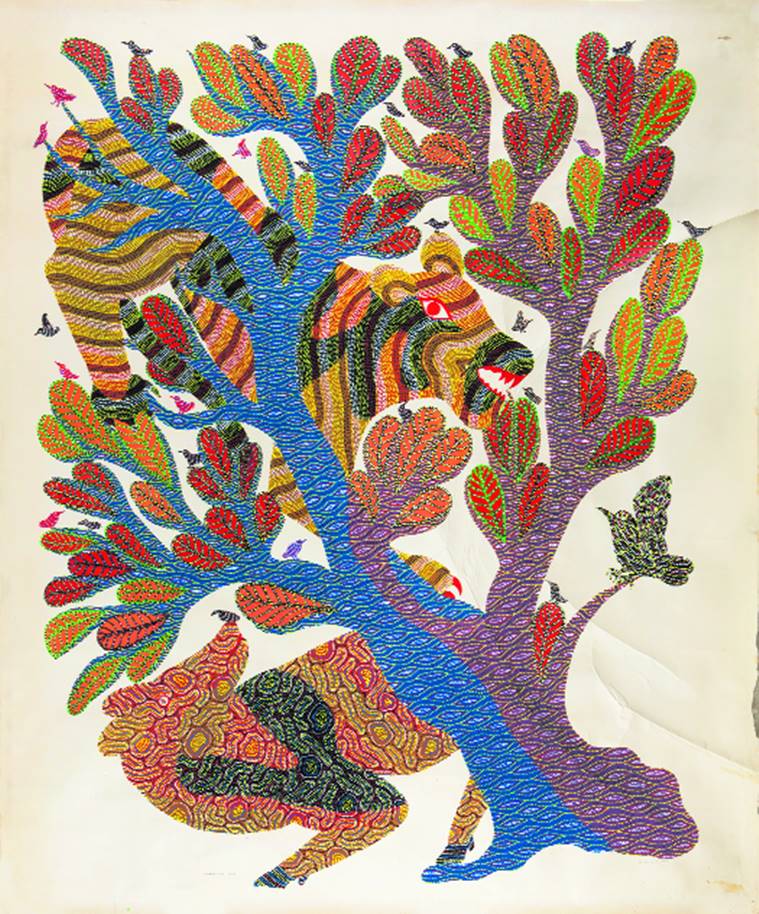

The beguiling work of Jangarh Singh Shyam, creator of his own artistic language, defies labels such as ‘tribal’, ‘folk’ and ‘Gond’

The bare bones of Shyam’s story are well-known enough: he was discovered in Patangarh, Madhya Pradesh, and mentored by artist Jagdish Swaminathan, who was the then director of Bharat Bhavan, a multi-arts complex and museum in Bhopal.

The most telling anecdote about the rise and tragic demise of artist Jangarh Singh Shyam is of the time when an art gallery in Delhi, exhibiting some of his works in 1988, told him that his usual attire of pants and shirt simply wouldn’t do for their publicity shots. It wouldn’t seem “authentic”, he was told, and was directed to wear only a loincloth and a turban to more closely resemble the gallery’s idea of a “tribal”. We are told this story by Jyotindra Jain, scholar of Indian art and former director of the National Crafts Museum in Delhi, who has also recorded it in his new book Jangarh Singh Shyam: A Conjurer’s Archive, published by the Museum of Art and Photography (MAP) in Bengaluru. Jain’s source was Shyam himself, who recounted the story when asked by the writer to pose for a photograph for the catalogue of the seminal 1989 exhibition “Other Masters: Five Contemporary Folk and Tribal Artists of India”. Jain writes, “The subtext is evident: to safeguard the authenticity of the tribal and his art, they must remain anchored in the past, and therefore the tribal cannot have a contemporary face — regardless of his nearly two decades of living in Bhopal and working in a modern, multi-arts complex in the city.”

The bare bones of Shyam’s story are well-known enough: he was discovered in Patangarh, Madhya Pradesh, and mentored by artist Jagdish Swaminathan, who was the then director of Bharat Bhavan, a multi-arts complex and museum in Bhopal. Shyam, despite little education and no training in art, was a quick study. He soon developed his unique artistic language, using it to convey memories of his childhood and the stories of gods, men and beasts that were his cultural inheritance. He exhibited nationally and internationally, becoming a well-respected artist and gaining prestigious commissions, including the painting of murals at the Charles Correa-designed Vidhan Bhavan in Bhopal. In 2001, however, Shyam hanged himself in his room during a residency at the Mithila Museum in Tokamachi, Japan. It is believed that he took his own life because he was depressed about being forced to stay back longer than he wanted and produce more work than he wished to.

Jain’s book goes far beyond the autobiographical details to examine how external mediations — interactions with modernist culture, exposure to new materials, techniques and so on — shaped Shyam’s art. It argues that far from being an outlier in modern Indian art history, Shyam was a key figure who was, even during his lifetime, frequently seen merely through the lens of his cultural background. The mislabelling of his work as “Gond art” is one result of this old reductive approach. Jain explains that the error begins with the belief that Shyam was a Gond. “He was actually a Pardhan. Pardhans share many cultural traits with Gonds, but they’re a separate community and are, in fact, looked down upon by Gonds,” he explains.

This is important also because it puts to rest the belief that Shyam drew on an existing “Gond art tradition”. The tradition that Shyam drew on, Jain says, was that of mythology and storytelling. “Women in Jangarh’s community used to make clay relief artwork, but his own work went beyond the decorative,” he says, adding, “Moreover, it wasn’t like there was a tradition of Pardhan art, like there was a tradition of Warli or Madhubani art”. Thus as creator of his own form of artistic expression — mediated by what he learnt at Bharat Bhavan and elsewhere — Shyam can’t be pushed into the “tribal” or “folk” art category. “He was, in every sense, a modern artist,” says Jain.

The discussion ‘A Conjurer’s Archive and Art Historical Divides’ by Asia Society India will take place at Visitor’s Centre, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, Mumbai, on March 7 at 6.30 pm

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario