Move Along Now

Chinmay Tumbe’s debut book traces the history of migration in India and locates it in the immediate socio-cultural context of the times.

Punjabi immigrants on board the Komagata Maru in Vancouver harbour Wikimedia Commons.

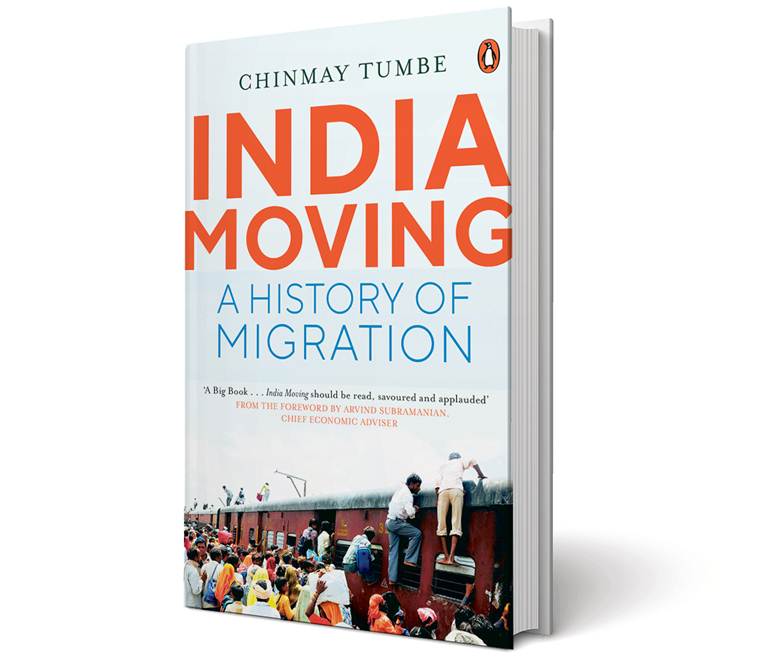

Book: India Moving: A History of Migration

Writer: Chinmay Tumbe

Publisher: Viking Penguin

Page: 264

Price: Rs 599

Writer: Chinmay Tumbe

Publisher: Viking Penguin

Page: 264

Price: Rs 599

Chinmay Tumbe’s first book is well timed. India Moving appears when Assam’s National Register of Citizens has become a lightning rod for old anxieties concerning migrants. Internationally, the migrant is a visibly distressed figure. The question of refugees in the Continent is vexing the very idea of a unified Europe, and in the US, Trump’s proposed wall has divided a nation.

Tumbe reminds us that migration is not necessarily across national borders. Huge populations are constantly on the move within India, from rural to urban, from city to city, sometimes for keeps, and sometimes cyclically, following employment opportunities. This is a significant observation, when politics is obsessed with the idea of inward migration in both modern and ancient times, as in the hypothesis of an Aryan invasion.

The region has been on the move from ancient times. History highlights the headline stuff — the arrival of armies in search of a fortune, or a future. The flight of locals from death and taxes does not get top billing, though millions more are thus affected. Besides, transhumance has been an annual feature of the calendar from the dawn of pastoralism. In later times, providers of labour like the Bihari bhaiyyas in the farms of Punjab, or aggregators of capital like the Marwaris of Kolkata, have altered the fortunes of entire regions. And travelling for an education is not a novelty. Long before the IITs and JNU, there were Nalanda and Taxila. And a sultan translocated his capital from Delhi to Daulatabad, an unusual case of forced migration.

Tumbe’s canvas comprises all of the historical space-time continuum in our region. That is both his asset and weakness. Since migration is an element of social, economic and even political history, the reader emerges with a deeper understanding of the past than the schoolbook accounts of the derring-do of vintage robber barons can provide. But the fabric is so wide that some parts are patchy. So, for instance, while Tumbe tells of the Gujarati Bhatias in Muscan, Aden and Zanzibar after the 16th century, one finds no mention of the Gujarati trading base on the island of Socotra, off the Horn of Africa, which dates back at least to the time of Christ. Similarly, while Tumbe writes that monasteries served as banking centres on trade routes, he does not explore the related story, of the microlithic nomads who transported goods on these routes. But he does go into the next chapter of the story, in which some of those nomads wandered a little too far and became the Roma of Europe.

Tumbe devotes more than a page to the Habshi (a corruption of Abyssinian) slave Malik Ambar, who rose to prominence in Ahmadnagar and became a thorn in Jahangir’s side. But there is no mention of the colourful Bob the Nailer, a native sniper of African descent — and possibly a descendant of the 10,000 Habshis in Ambar’s army — whose rifle took a dreadful toll on the English at the Lucknow Residency in 1857. This patchiness extends to background material, too. India Moving is based on very extensive reading and 33 pages of notes are provided, but one found no reference to Judith M Brown, whose work on the modern Indian diaspora is fairly inescapable.

But this is only inevitable. A book of 260-odd pages cannot be expected to exhaustively document the human traffic of five millenia. Tumbe catalogues 32 classes of people who were travelling routinely even in pre-modern times, ranging alphebatically from ascetics and ayahs by way of spies and students to weavers and wives — “and that catch-all word, workers”. The age of sail and steam accelerated mobility and made possible journeys to the other side of the world. In London, Dean Mahomet invented what the English are pleased to call curry. Sikh farmers appeared in California, and in Canada, the Komagata Maru incident happened. This growing acceleration produced what Tumbe calls the Great Indian Migration Wave, which persists into contemporary times, featuring men without women in the world’s cities, from Dubai to Kolkata.

Tumbe connects the dots on the migratory routes very well. “Mumbai’s red light area, Kamathipura,” he writes, “had an old connection with the Kamathi workers from… present-day Telangana… which continues to be a source of trafficking.” He traces the Indian diaspora in the Gulf to the exertions of George Bertrand Reynolds, a long-serving PWD engineer in India who had become field manager of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, which had discovered a field in Persia in 1908. In less than two decades, over 3,000 Indians were working in Persia and due to increasing labour demand, the company opened a recruiting office in Bombay, setting the template for future HR outfits.

Tumbe has explored the major trading and mercantile communities which have been active in the modern era, including the indigenous Marwaris (the Birlas, for instance), Sindhis (the Hindujas), some Punjabi groups, as well as immigrants like the Baghdadi Jews (the Sassoon family, for instance) and Armenians like Calcutta’s Sir Catchick Paul Chater and Arathoon Stephen. Their success stories stand a little apart from the Migration Wave, which largely consists of labour travelling in the hope of encountering capital.

Today, the wavefront consists of information technology workers and medical personnel who have made careers in Silicon Valley and Harley Street, and are unlikely to return home. However, apart from the Sikhs and Patels who own a significant chunk of the US hospitality industry, no community seems to have shown the unified sense of purpose which marked the rise of the Marwaris.

Numerous accessible works cover the modern period, in which these groups have been active. But work on the ancient period is generally of an archaeological nature, and inaccessible to the lay reader. Tumbe’s work begins at the beginning, underscoring the need to make prehistory accessible. His book is not a formal history, despite the claim in the subtitle, but it points the way to future popular histories, which need to be written.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario