The Wars They Lived

Battles rage and freedom cries ring loud as people live and love in fictional Pipli town, in this novel set in the 1940s

Daman Singh’s Kitty’s War is not a historical account but a work of fiction, set in very real times.

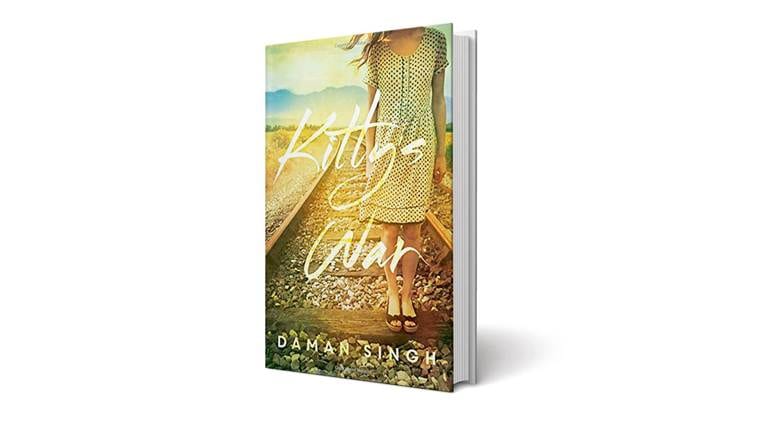

Book: Kitty’s War

Writer: Daman Singh

Publisher: Tranquebar

Page: 243

Price: Rs 350

Writer: Daman Singh

Publisher: Tranquebar

Page: 243

Price: Rs 350

Change almost looks like war these days — disruption is touted as a good thing and stability is for dunces. But what has change brought about today, in all its cataclysmic glory? Global political upheaval, war in large parts of the world, technology, general fragmentation and challenges to the idea of a nation state — all of which found clear echoes in another time, most noticeably when the world was at war for the second time in the last century.

Some wonderful books in the recent past have recounted what the Second World War meant to human lives — not just states or governments, but people who lived and starred in them. Raghu Karnad’s Farthest Field: An Indian Story of the Second World War and Srinath Raghavan’s India’s War: The Making of Modern South Asia are meticulous accounts of the common people waging wars, losing lives and ending up constituting the larger mosaic of accounts we have read in history books. No Place to Lay One’s Head by Françoise Frenkel, a young Jewish Pole who tried to set up a French bookstore in Berlin in the face of Nazi build-up, also offers a close-up of what tumult and war would have meant to lives lived then, and not just to secretaries of state.

Daman Singh’s Kitty’s War is not a historical account but a work of fiction, set in very real times: a little railway colony, Pipli Junction, in December 1941, just when the Japanese are “closing in on India” and the Indian Independence movement is picking up momentum, is the backdrop for the action. The experiences of Katherine Riddle, combating a broken heart, ‘Ayah’ and the Indian station-master combine to make for a compelling account.

When asked point-blank by Emily, as to what ended her romance, Kitty says clearly; “Its just this stupid war, it changed everything.”

Where Singh’s novel does very well is in organising the pace of the story. Her narration has a certain languidness which makes it seem like it was written in the specific time she is describing. Contemporary novels that are written about a specific time in the past struggle to locate and balance their tone somewhere between the time they are set in, and of when they are actually being read, in the present. Kitty’s War, however, takes you right there. At no point does Singh lose sight of the original time-space setting that her fictional characters inhabit. Allan Octavian Hume, a former Imperial Civil Service (ICS) member, also a founder-member of the Congress party, finds mention — he is discussed in the context of his preoccupations as a naturalist and an ornithologist, for his journal Stray Feathers. Kitty’s father, also a civil servant, recalls how EC Stuart Baker, former Inspector General of Assam, doubled up as a birdwatcher. Ayah’s ruminations also throw up fundamental questions about colonisers, invaders and who displaces whom when they invade a country.

This is Daman Singh’s third novel, and one might say the finest so far. She shows, through her other works of non-fiction, an enviable range, even if it is just two books so far. One is of people and forests in Mizoram and the other book is her memoir of her parents, Dr Manmohan Singh and Gursharan Kaur. The memoir stops at the point when Manmohan Singh starts his ten-year term. Both her non-fiction works demonstrated meticulous research and this work of fiction has benefited from that rigour. This makes Kitty’s War a rewarding read.

The year 1941, at first glance, appears rather non-consequential, but this is the year when Rabindranath Tagore died, Subhash Chandra Bose famously escaped from house arrest in Calcutta, Pearl Harbour wasattacked, and Stalin’s Soviet Union was invaded by Nazi Germany. But this was still well before the direction of the War had taken any concrete form. The terrible Bengal famine was two years away and it was the calm in the national political landscape before the storm broke in the form of Quit India next year. However, churning is a daily routine in the lives of the protagonists. It offers a sense of time passing by for the many lives located near the rail junction.

Freedom, in all its manifestations, is a theme that flits across every page, sometimes bursting through, like when Frank says: “You never know what freedom is till it’s taken away from you. When you lose your dignity and self-respect, your faith in justice, humanity — and most of all — when you lose hope..”

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario