Chinese traditional residences at a crossroads

The preservation of the Chinese traditional residences is in fact a memory and interpretation of the history. Adapted to the local climate and geographical features, Chinese traditional residences vary in style and abound in forms.

The 2008 Beijing Olympics brought great luck to Jing Jichang and Wang Zhixi, a couple dwelling in an alley, called hutong in Beijing dialect. In the downtown of Shichahai, it is not difficult to locate No. 12 Dajinsi hutong, which is Jing’s house, after walking through a few hutongs. Inside this typical quadrangle are a screen wall, the second door, the awning, some pomegranate trees, a fishbowl, red lanterns, Taihu Stone rockery, and a birdcage.

Jing’s house was designated to accommodate foreign visitors during the Olympics. As a result, Mr. and Mrs. Peter, a couple from Germany, moved into this quadrangle. While sitting in the cozy and sunny room among fragrant flowers and chirping birds in the courtyard, the guests and the hosts talked over tea, sharing the everyday life of an average household. At breakfast, the Peters had a taste of local delicacies such as bean juice and fried dough rings. Just out of interest, they could even learn Taichi from Mr. Jing.

Modern life has been so amazingly hectic that the leisurely life in the hutong is really enviable. The community around Shichahai, which is famous for its extensive body of water, has long been hailed as a Wonderland for the grass roots. Enticed by the life here, many visitors come for a game of shuttlecock with local middle-aged women, or a sightseeing tour on the rickshaw that takes one through the narrow lanes, while hearing the music from the Huqin, a two-stringed instrument, as you go around the quadrangles.

The poetic nature of Shichahai now appears invaluable to the human soul.

In one of his poems, German lyric poet Friedrich Hölderlin wrote: “Full of merit, yet poetically, man dwells on this earth.” Despite the popularity of “poetical dwelling” in present-day real estate advertisements, to a considerable number of people, “poetical dwelling” remains tantalizingly out of reach.

WHAT DOES THE FUTURE HOLD FOR THE HOME?

The Jing’s quadrangle along with the narrow and long lane in front of it is typical of Chinese traditional residence in Beijing. As more and more old areas are upgraded and more and more people move to the suburbs, the number of hutongs dwindled from 7,000 in 1949 to 3,900 in the 1980s. They have been disappearing at an annual average rate of 600 ever since.

There is a mixed feeling about the dismantling of these old communities. On one hand, the local people long for improvements in their living conditions; on the other hand, they can hardly tear themselves away from the familiar community, because they will be separated from each other once they move to the outskirts of the city. The tidy and newly-built communities in suburbs are well-furnished with monitor cameras and regularly patrolled security guards. But are they the ideal home?

On her second visit to Chengdu, Long Yingtai, a famous scholar of cultural studies, heaved a sigh of sorrow: “I’ve lost Chengdu!” She was shocked at the rate, Chinese traditional residences were disappearing and giving way to modern skyscrapers. “Chunxi Street, for example, used to be one of historical interest. Now it is the same with any other city, the street has followed Western style.” In “Where Does Hong Kong Head for”, one of her popular articles written before, she mentioned “We’ve got to think where the city – our home – is heading for before we hand the green land to a corporation that would reduce it to a construction site.”

Obviously the sentimental words are reminiscent of the conflict between preservation and development in urbanization.

The 1980s witnessed a national zest for development in China, initiating a facelift campaign that resulted in fundamental changes to urban areas. Even worse, the real estate market was flooded with all types of Western style buildings like North-American, European, and Australian styles.

With large lanes, large squares, landscaped roads, and skyscrapers, all cities are following the foot of American or European styles, taking on the same look. Wellfurnished or decorated as they are, the apartments reinforced with iron and concrete are distancing themselves emotionally from nature. Poetical life is gone. Essential to a house is the garden. However, many have a house with no garden other than the poor, tiny one on the street that is shared by many.

BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO

CHINESE TRADITIONAL ARCHITECTURES

Adapted to the local climate and geographical features, Chinese traditional residences vary in style and abound in forms. Most of the houses remaining in use date from the Ming or Qing dynasties. With carved beams and painted rafters, upturned eaves and winged ridges, they appear concise in shape, exquisite in ornamentation, and classic in style. Meanwhile the zigzagged corridor and deep courtyard demonstrate the harmony between the residence and nature. Among the famous and typical Chinese architectures are quadrangles in Beijing, grand residences in Shanxi, ancient waterfront towns, Anhui-style architecture, and the Hakka Tulou.

Ancient Waterfront Towns

These towns are mainly distributed in the southeast of China. Among the famous towns are Zhouzhuang, Lujiao and Tongli in Jiangsu and Xitang, Wuzhen, and Nanxun in Zhejiang. Their distinctive feature is the charming scenario of “bridges over water and households aligned along the banks.” In these towns, almost every house is on the waterfront, hence accessible by boat. The rivers and the streets are parallel to each other. The streets are connected by arch bridges. The houses are built along the rivers. With multiple ridges and high eaves, large houses have deep courtyards and winding corridors. The stone steps on wharfs, wooden pillars, graceful eaves, and their reflection in water, teamed with the twittering oars and indistinct fishing songs, constitute the romantic charm of these waterfront towns that feature arch bridges, babbling rivers, and ancient houses.

Quadrangles in Beijing

The quadrangles date back to the second half of 13th century when the Yuan Dynasty chose Beijing as its capital. Usually built along an east-west alley, a typical quadrangle faces south. It is usually made up of a main house in the north, an opposite house in the south, and 2 side houses in the east and west. In the middle of the quadrangle is the courtyard, which is big enough for growing flowers and water vats for goldfish. Besides, it is a place for walking, lighting and ventilation and a venue for the residents to cool down, relax, or do domestic chores. An enclosed structure, the quadrangle has only one gate. The layout reveals the traditional lifestyle of ordinary people in northern China.

Anhui-style Residence

These residences are mainly found around Mount Huangshan and Wuyuan County in Jiangxi. One of the important architectural schools in ancient China, Anhui style finds its way mainly into ancestral temples, memorial arches, and traditional gardens. Anhui-style architecture employs bricks, wood, and stone as its materials. The entire residence is centered on a “tianjing”, a tiny square courtyard in each house. The wooden structure features engraving and exquisite decorations of high artistic value. Anhui-style architecture stresses the harmony of man with nature. More often than not, the residence nestles snugly in the embrace of a mountain and adjoins a river.

Grand Residence in Shanxi

These residential complexes combine the features of northern and southern architectures. Stately and magnificent, they are buildings of the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911). There are both four-sided and threesided courtyards. Free of any fixed composition, the residences in the mountain areas usually nestle at the foot of a hill. An eminent businessman or official boasts a residential complex, which includes the main courtyard, the side courtyard, the study courtyard, the embroidery building, and the garden. With an imposing gate, carved beams, and painted rafters, the residence looks marvelous. Neatly constructed, the Qiao Family Residence and Yan Xishan Residence, for example, appear stately and imposing outside and grand and gorgeous inside. They are typical residence of the feudal clans in northern China.

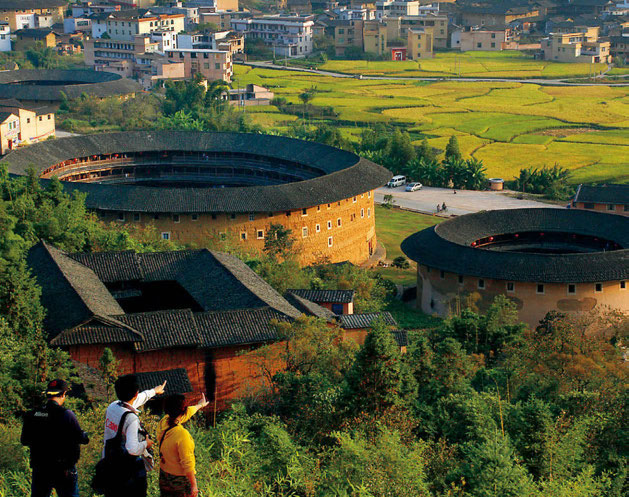

The Hakka Tulou

Large circular houses, the Hakka Tulou are mainly distributed in the bordering areas of Fujian, Guangdong, and Jiangxi. These buildings date back to the Tang and Song Dynasties and thrived during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Each Tulou is composed of a courtyard, three halls, two side buildings, and a circle of walls. In remote mountain areas, the Hakka people built this defensive fort to prevent thefts or conflicts with the locals. An ordinary Tulou covers an area of 8-10 mu (about 1.6 acres); whereas a large one may measure over 30 mu (about 4.8 acres). A fort for a Hakka clan, the Tulou has several bedrooms, a kitchen, halls of different sizes, a well, a pig sty, a henhouse, a washing closet, a storehouse, etc. People here form a self-sustaining mini-community that allows them to feel content with their lot.

OLD TOWNS PRESERVED AT LAST

The impact of modernization is also felt in such “Dreamlands of Water” as Zhouzhuang and Wuzhen. These traditional towns that dot the south of the Yangtze River distinguish themselves from other towns. In terms of layout, the town is built near a river, with the market along the river, and the streets as the banks, making it convenient for both water and land transportation. All these constitute a leisurely and pleasant picture of bridges, rivers, and houses. The architecture itself, including the white walls, grey tiles, narrow and deep lanes along the rivers, rolling gables, and rectangular courtyards, gives expression to the time-honored feudal ethics as well as the literati’s high character, the businessmen or little officials’ self-effacement, or the average dwellers’ simplicity.

The 1980s witnessed not only a great development of rural enterprises but also large-scale destruction of bridges for wider streets and rivers for better roads when villages and towns on the plain south of the Changjiang River were trying to encourage investment by improving the infrastructure. Consequently, many traditional towns suffered an irretrievable loss due to the development drive.

Professor Ruan Yisan, who has been rushed off his feet advocating for the protection of ancient cities, towns, architectures, and cultural relics for more than 30 years, is a witness to the change in the south of the Changjiang River. He gets heavily involved in the protection of the traditional towns himself. Professor Ruan said with a sigh, “There used to be more than 40 old towns in this area, but we have only managed to protect six of them. Once poetical and picturesque, the towns were a pleasant sight. Xitang is graceful, Wuzhen is scenic and Nanxun is spacious.” The six towns that have survived are now at a crossroads: cultural protection or commercial development.

From 1998 to 2002, the stores in Zhouzhuang increased from 200 to more than 600. In a short span of four years, hundreds of residences were reconstructed into stores. With the traditional lifestyle getting less and less appealing to the young, old towns are losing their native residents, resulting in the rise of an aging population and empty nests.

At the First Zhouzhuang Symposium on Protection and Development of Ancient Towns, Mr. Ruan Yisan pointed out that the protection of ancient towns is to not only for the protection of historical architectures and the town’s layout but the dwellers and their ethos as well, helping to assimilate all of them into modern society. His words left us pondering whether the life in ancient lanes is incompatible to modern apartments.

GLORY REGAINED

The quadrangle still holds its value, so do the ancient wall, the classic garden, and the little bridge over streams. However these Chinese architectures seem to strike a discordant note amid the harmonious western architectures in China.

It is a novel idea for a Chinese architect to design Chinese-style architecture because the native architect in China is usually busy creating western-style buildings. Traditional Chinese residences are not suitable for modern living. High cost, low density, and low profit margin have displaced traditional architectures from the mainstream architectures in China.

Over the last decade, however, those who have distanced themselves from tradition the farthest have held the highest opinion for the Chinese-style architecture. Most of the purchasers of Chinese-style buildings are the returnees or overseas Chinese. Improved and refurnished, Chinese-style architecture is displaying a promising prospect of returning to the mainstream.

In an effort to preserve the Chinese traditional residences, some measures have been taken: building new residence without dismantling old ones, preserving the old without impeding development, and restoring the old houses to their former glory. In Beijing’s Dongcheng District, local residents invest in reconstructing their quadrangles, adding bathrooms and water closets to the traditional courtyards. In Shanghai’s Jing’an district, the government has initiated an attempt to get residents return by subsidizing their reconstructed Shikumen houses. Although small in scale, the reconstruction of traditional houses in Beijing and Shanghai has attracted much attention. This indicates an initiative in community construction. “The dynamics of a city comes from the public,” said Wu Liangyong, an academician of China Academy of Sciences.

On July 1, 2008, the long-awaited Regulation on the Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities, Towns and Villages was promulgated. This is a legal document that specifies the necessity for “comprehensive protection of famous historical and cultural cities, towns and villages” and “the preservation of historical and cultural heritages in their authenticity and entirety”.

To preserve traditional residence is in fact a memory and interpretation of the history, culture, lifestyle, and custom of the past. Essential to it is the cultural confidence of the nation.

Published in Confucius Institute Magazine

Number 03.Volume III. July 2009.

Number 03.Volume III. July 2009.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario