The Form and Function of the Prophet’s Mosque during the Time of the Prophet

by Omer SpahicPublished on: 4th August 2020

In the wake of the hijrah (migration), the city-state of Madinah underwent significant changes in virtually all its features including changing its name from Yathrib to Madinah. The significations of the latter unmistakably implied the new character, purpose and aspirations of the rising city-state.

***

Editor’s Note: This is a short article extracted from a book titled “History and Architecture of the Prophet’s Mosque” by Omer Spahic, 2019, www.daralwahi.com. The book may be obtained from here.

***

Abstract

When Prophet Muhammad migrated from Makkah to Madinah, the first and immediate task relating to his community-building mission was constructing the city’s principal mosque. Every other undertaking, including building houses for the migrants a majority of whom were poor and practically homeless, had to be deferred till after the Prophet’s Mosques was completed. When completed, the form of the Prophet’s Mosque was extremely simple. Its unpretentious form notwithstanding, the Mosque since its inception served as a genuine community development centre, quickly evolving into a multifunctional complex. The Mosque was meant not only for performing prayers at formally appointed times, but also for many other religious, social, political, administrative and cultural functions. It became a catalyst and standard-setter for civilization-building undertakings across the Muslim territories. In this paper, the significance of the Prophet’s Mosque as a prototype community development center is discussed. The architectural aspect of the Mosque and its reciprocal relationship with the Mosque’s dynamic functions is also dwelled on. The main paper, out of which this article is extracted, is divided into six sections: 1) From Yathrib to Madinah; 2) Madinah (the city) as a microcosm of Islamic civilization; 3) The introduction of the Prophet’s Mosque; 4) The main functions of the Mosque; 5) The architecture of the Mosque; 6) Seven lessons in architecture.

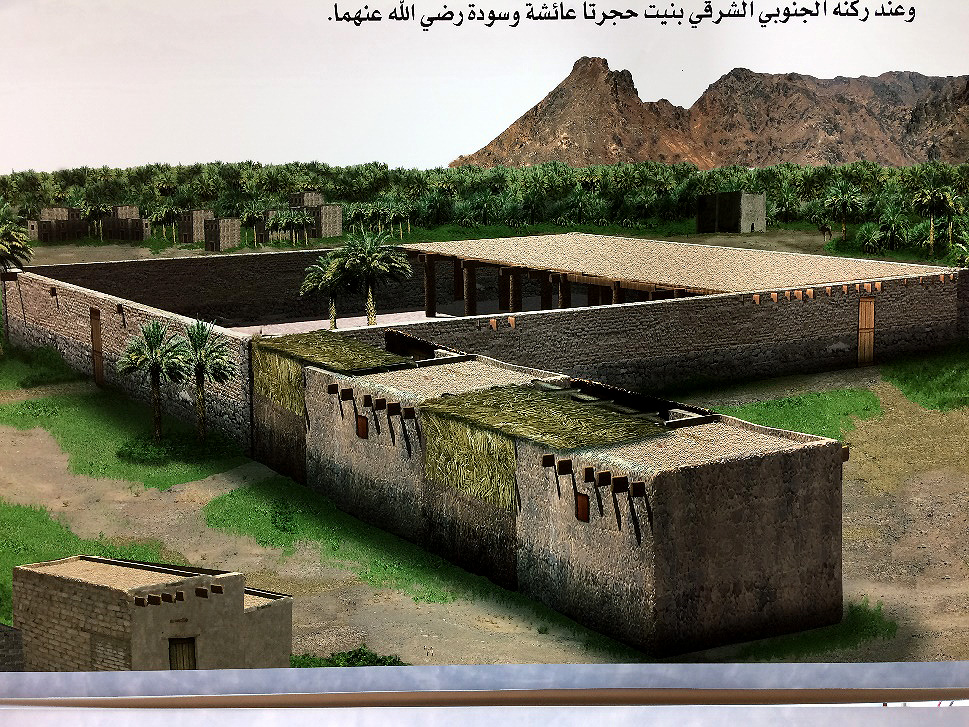

Figure 1. Prophet Muhammad’s Mosque before its first expansion by the Prophet himself in the 7th year of the hijrah (629 CE). At first, for about 16 or 17 months, the qiblah or prayer direction was towards al-Masjid al-Aqsa in Jerusalem. (Courtesy of the Museum of Dar al-Madinah in Madinah)

In the wake of the hijrah (migration), the city-state of Madinah underwent significant changes in virtually all its features including changing its name from Yathrib to Madinah. The significations of the latter unmistakably implied the new character, purpose and aspirations of the rising city-state.

Since people are both the builders and demolishers of every civilizational accomplishment, and since they are the establishers and inhabitants of cities, the Prophet through a number of heavenly inspired legislative moves paid some special attention to bringing up virtuous and honest individuals who formed a healthy, virtuous and dynamic society. The believers’ relationships with God, the environment and other people were set to become and remain perpetually sound and just, making the living places of theirs – and if given a chance, the whole of earth – better and more conducive to a pious and truly productive living.

The first city component introduced by the Prophet to the city of Madinah was the mosque institution, the Prophet’s Mosque. Since its inception, the Mosque functioned as a community development center. Different types of activities were conducted within its realm. In addition to serving as a place for congregational prayers, as well as for other collective worship (‘ibadah) practices, the Mosque, likewise, furnished the Muslims with some other crucial social amenities and services. It was the seat of the Prophet’s government, a learning center, a place for some medical treatments and nursing, a detention and rehabilitation center, a welfare and charity center, and a place for some legitimate leisure and recreational activities.

When completed, the form of the Prophet’s Mosque was extremely simple. Its unpretentious form notwithstanding, to Muslims the Mosque instantly became a catalyst and standard-setter for civilization-building.

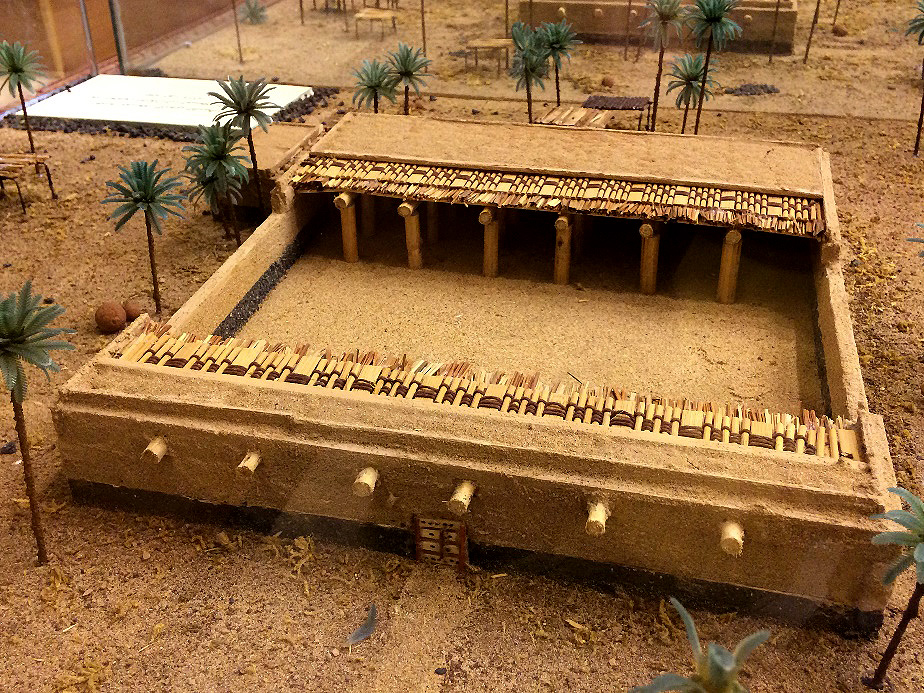

At first, the Prophet’s Mosque was just an enclosure. Its walls, made of mud brick and raised over stone foundations, enclosed a roofless and unpaved area of approximately 1,200 square meters. There was no roofed section; one was introduced later as a result of heat. Three entrances pierced the southern, eastern and western walls. The northern side was the qiblah (prayer direction) wall facing al-Masjid al-Aqsa in Jerusalem. After 16 or 17 months following the hijrah, the qiblah was redirected from al-Masjid al-Aqsa to al-Masjid al-Haram and so, the simple form of the Prophet’s Mosque responded accordingly: the entrance in the southern wall was bricked up since it started to function at once as a new qiblah side, while a new entrance was perforated in the northern wall which heretofore functioned as the qiblah side (Creswell, 1989, p. 4; Hillenbrand, 1994, p. 39).

Figure 2. Prophet Muhammad’s Mosque after its qiblah change, but before its first expansion by the Prophet. (Courtesy of the Museum of Dar al-Madinah)

About three years before his death, i.e., in the 7th year of the hijrah (629 CE), the Prophet, while duly answering the needs created by the rapid increase of worshippers as well as the rapid expansion of Madinah as a prototype Muslim city-state, significantly enlarged the Mosque, making it measure approximately 2,500 square meters.

The following is a standard description of the form of the Prophet’s Mosque at the time of the Prophet’s demise as given by most scholars: “In the construction method a stone foundation was laid to a depth of three cubits (about 1.50 meters). On top of that adobe, walls 75 cm. wide were built. The Mosque was shaded by erecting palm trunks and wooden cross beams covered with palm leaves and stalks. On the qiblah direction, there were three porticoes, or colonnades, each portico had six – or even eight – pillars (palm trunks). On the rear part of the Mosque, there was a shade, where the homeless muhajirs (migrants) took refuge. The height of the roof of the Mosque was equal to the height of a man (with his hands raised)” (Hamid, 1996, p. 226; al-Samahudi, 1997, vol. 2 p. 481).

Figure 3: Prophet Muhammad’s Mosque after its first expansion by the Prophet. (Courtesy of the Hadarah Tayyibah Exhibition held in Madinah in 2010-2012)

Based on the Prophet’s building experiences, we can conclude that Muslim architecture is not to be concerned about the form of buildings only. Authentic Muslim architecture signifies a process where all the phases and aspects are equally important. It is almost impossible to identify a phase or an aspect in that process and consider it more important than the others. The process of Muslim architecture starts with having a proper understanding and vision which leads to making a right intention. It continues with the planning, designing and building stages, and ends with attaining the net results and how the people make use of and benefit from them. Muslim architecture is a fine blend of all these factors which are interwoven with the treads of the belief system, principles, teachings and values of Islam.

Furthermore, Prophet Muhammad taught that at the core of Muslim architecture lies function with all of its dimensions: corporeal, cerebral and spiritual. The role of the form is an important one, too, but only inasmuch as it supplements and enhances function. Muslim architecture should embody the teachings, values and principles of Islam as a complete system of thought, practice and civilization, because it functions as the physical locus of human activities, facilitating and promoting them. It should be man-oriented, upholding his dignity and facilitating his spiritual progression while in this world. Architecture is a means, not an end.

Figure 4. A replica of one of the Prophet’s houses where his wife A’ishah resided. (Courtesy of the Hadarah Tayyibah Exhibition held in Madinah in 2010-2012)

Moreover, one of the most recognizable features of Muslim architecture should always be its sustainability penchant. This is so because Islam, as a total worldview, ethics and jurisprudence, aims to preserve man and his total wellbeing, i.e., his religion, self, mental strength, progeny (future generations) and wealth (personal, societal and natural). The views of Islam and Prophet Muhammad concerning the natural environment and man’s relation thereto are unprecedented.

Figure 5. A replica of the Prophet’s minbar (pulpit). (Courtesy of the Hadassah Tayyibah Exhibition held in Madinah in 2010-2012)

It goes without saying, therefore, that without Islam there can be no legitimate Muslim architecture. Likewise, without devout Muslims, who in their thoughts, actions and words epitomise the total message of Islam, there can be no Muslim architecture either. Muslim architecture is a framework for the implementation of Islam, a framework that exists in order to facilitate, encourage and promote such an implementation. Hence, properly perceiving, creating, comprehending, studying and even using Muslim architecture, cannot be achieved in isolation from the total framework of Islam with its comprehensive worldview, ethos, doctrines, laws, practices, genesis and history. Any attempt or method that defies this obvious principle is bound to end up in failure, generating in the process sets of errors and misconceptions. Indeed, the existing studies on Muslim architecture, by Muslim and non-Muslim scholars alike, and the ways in which Muslim architecture is taught and “practiced” today, is the best testimony to the confusion that surrounds Muslim architecture as both a concept and sensory reality.

Prophet Muhammad’s time represented the first and certainly most decisive phase in the evolution of the identity of Muslim architecture, as it is known today. What the Prophet did with regard to architecture, by and large, amounts to sowing the seeds whose yield was harvested later especially during the Umayyad and Abbasid epochs and beyond. Prophet Muhammad laid the foundation of true Muslim architecture by introducing its veiled conceptual aspects that were later given their different outward appearances as dictated by different contexts. The aspects contributed by the Prophet to Muslim architecture signify both the quintessence of Muslim architecture and the vitality that permeates its every facet and feature. Thus, the permanent and most consequential side of Muslim architecture is as old as the Islamic message and the Muslim community, but at the time of the Prophet it could take no more than a simple and unrefined physical form. The evolution of the Prophet’s Mosque in Madinah was the epitome of the Prophet’s contributions to the evolution of the revolutionary phenomenon of Muslim architecture.

The following sources were used in main paper:

- ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, Abdullah. (1992). Mujtama’ al-Madinah fi ‘Ahd al-Rasul. Riyad: Jami’ah al-Malik Sa’ud.

- ‘Abdullah, ‘Umar Faruq. (2006). Islam and the Cultural Imperative. Retrieved September 22, 2007 from http://www.crosscurrents.org/abdallahfall2006.htm.

- Al-‘Umari, Akram Diya’. (1991). Madinan Society at the Time of the Prophet. Herndon: The International Institute of Islamic Thought.

- Abu Dawud, Sulayman b. al-Ash‘ath. (1997). Sunan Abi Dawud. Beirut: Dar Ibn Hazm.

- Abu Zahrah, M. (1970). The Fundamental Principles of Imam Maliki’s Fiqh. Retrieved September 18, 2007 from http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/ABewley/usul12.html.

- Ahmad b. Hanbal. (1982). Musnad Ahmad b. Hanbal. Istanbul: Cagri Yayinlari.

- Al-‘Asqalani, Ibn Hajar. (1978). Fath al-Bari bi Sharh Sahih al-Bukhari. Cairo: Maktabah al-Kulliyyat al-Azhariyyah.

- Ayyad, Essam. (2013). The ‘House of the Prophet’ or the ‘Mosque of the Prophet’? Journal of Islamic Studies, 24, pp. 273-334

- Al-Bukhari, Muhammad b. Isma‘il. (1981). Sahih al-Bukhari. Beirut: Dar al-Fikr.

- Creswell, K.A.C. (1989). A Short Account of Early Muslim Architecture. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

- Al-Farabi, Abu Nasr. (1985). Al-Farabi on the Perfect State (al-Madinah al-Fadilah). A revised text with introduction, translation, and commentary by Richard Walzer. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hamid, Abbas. (1996). Story of the Great Expansion. Jeddah: Saudi Bin Ladin Group.

- Hillenbrand, Robert. (1994). Islamic Architecture: Form, Function and Menaing. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Hillenbrand, Robert. (1999). Islamic Art and Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Ibn Kathir, Abu al-Fida’. (1985). Al-Bidayah wa al-Nihayah. Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyyah.

- Ibn Khaldun, ‘Abd al-Rahman. (1967). The Muqaddimah. Translated from Arabic by Franz Rosenthal. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ibn Majah, Muhammad. (2008). Sunan Ibn Majah. New Delhi: Kitab Bhavan.

- Ibn Sa’d. (1957). Al-Tabaqat al-Kubra. Beirut: Dar Sadir.

- Al-Kattani. (1980). Al-Taratib al-Idariyyah. Beirut: Dar al-Kitab al-‘Arabi.

- Lings, Martin (Abu Bakr Siraj al-Din). (1983). Muhammad. Kuala Lumpur: A.S. Noordeen.

- Lynch, Kevin. (1998). Good City Form. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Muhammad Mumtaz Ali, Islam and the Western Philosophy of Knowledge, (Petaling Jaya: Pelanduk Publications (M) Sdn, Bhd., 1994).

- Muslim, Ibn al-Hajjaj. (2005). Sahih Muslim. New Delhi: Islamic Book Service.

- Al-Nasa’i, Ahmad. (1956). Sunan al-Nasa’i. Lahore: Maktabah al-Salafiyyah.

- Al-Sabuni, Muhammad. (1981). Mukhtasar Tafsir Ibn Kathir. Beirut: Dar al-Qur’an al-Karim.

- Al-Samahudi, ‘Ali b. Ahmad. (1997). Wafa’ al-Wafa. Beirut: Dar Ihya’ al-Turath al-‘Arabi.

- Al-Tabari, Ibn Jarir. (1985). The History of al-Tabari. New York: State University of New York Press.

- Al-Tirmidhi, Muhammad b. ‘Isa. (2010). Jami’ al-Tirmidhi. Beirut: Dar al-Risalah al-‘Alamiyyah.

- Volkmar, Enderlein. (2000). Syria and Palestine: The Umayyad Caliphate. Inside: Islam, Art and Architecture. Edited by: Markus Hattstein & Peter Delius. Cologne: Konemann.

- Wan Daud, Wan Mohd Nor. (1989). The Concept of Knowledge in Islam. London: Mansell Publishing Limited.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario