Connecting the Dots

Through illustrations, oil paintings, wooden shields and new-media installations, an exhibition in Delhi showcases the centuries-old Australian Aboriginal art tradition

Franchesca Cubillo, curator of the exhibition Divya A

In 1788, the British arrived in Australia with a fleet of 11 ships, carrying about 1,500 people. They landed at Sydney’s Botany Bay, which they would turn into a prison colony. This was the land inhabited by the Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders for thousands of years.

“When the British arrived in Australia, they thought the Australians were one people, but what they discovered was 300 different tribes, each with their own language, rituals and art motifs,” says Franchesca Cubillo, curator of the exhibition, ‘Indigenous Australia: Masterworks from National Gallery of Australia’, at National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), Delhi.

The show features 102 artworks, with the oldest work dating back to the late 1800s, and includes paintings on canvas and bark, weaving, sculpture, new media, prints and photography. “This showcase demonstrates that the art of Indigenous Australia — one of the oldest continuous artistic traditions in the world — is as timeless as it is contemporary,” says Cubilio.

A modern illustration mounted on the wall reads “Ash on Me”. The 2008 work by 37-year-old Australian artist Tony Albert shows how Aboriginal people are represented in the Australian-subculture today. A collection of ashtray souvenirs sold outside Aboriginal habitats have been fixed inside the letters ‘ash on me’. Cubillo says, “Ashtrays with faces of Aboriginal people signify how inappropriate it may be for us to put cigarette butts on someone’s face.”

Australia’s tryst with the British also gave a leg up to the Aboriginal art as many of them started documenting the indigenous people as well as their art. Even as the first evidence of Aboriginal art, rock engravings, date back to 30,000 years, Cubillo says their first works on paper constitute illustrations of their daily life, rituals and ceremonies, made using earth colours. Standing before a work credited to Mickey of Ulladulla, Cubillo explains, “The British could not pronounce Aboriginal names, so they gave them their own names.” Mickey is the name given to the artist by the British, while Ulladulla stood for the region he came from.

While the early works by the Aboriginals, done in the 1800s, were fairly simple, Cubillo says the second movement in the Aboriginal art came in the 1930s. A huge work on canvas done by Danish Mellor, titled Paradise, reminds one of blue-and-white Chinese pottery. The work has an image of native Australian people as well as animals printed on chinaware-like print. On the British fascination for Chinese pottery, Cubillo says this work also signifies how they wanted aesthetic things in the drawing rooms. “The British wanted to consume the exotic, but from a distance,” she says.

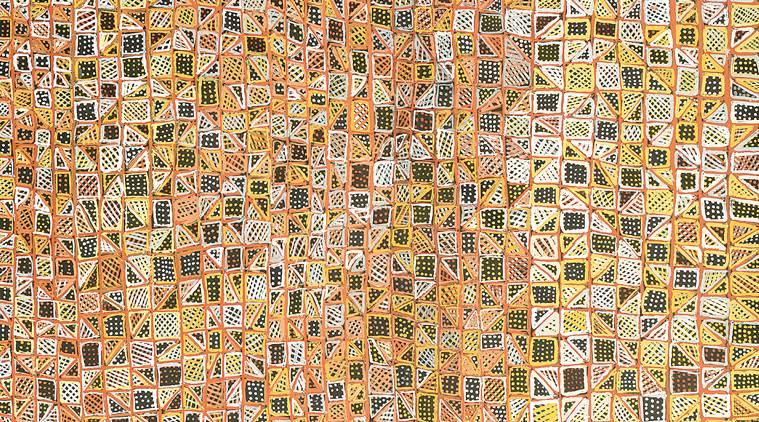

The largest space in the exhibition is devoted to contemporary Aboriginal art, created by artists living currently in remote corners of Australia. Their typical mythology and iconography make an appearance, showcasing how the tradition of Aboriginal art has been a continuous culture, and has survived through the ages, says Cubillo. Most of these works are dedicated to the ancestors, using symbols in place of figures. A huge section is also devoted to topographical works, with the aboriginals offering a bird’s eye view of their land, emerging from their imagination.

Galarrwuy Yunupingu, a towering leader of the Australian indigenous community, had remarked in 1989: “English is incapable of describing our relationship to the land of our ancestors. We decided to describe it in a way we hoped non-Aboriginal people would understand; through pictures. If they wouldn’t listen to our words, they might try and understand our paintings.” It is perhaps this concept that finds resonance in this section of the showcase.

Pausing before a giant canvas painted with spiral lines, created by a woman aboriginal artist, Emily Kam Kngwarray in 1995, Cubillo says, “Aboriginal art is more popular than any other art in Australia. In fact, the highest price that a work has fetched till date has been done by this artist, who recently passed away.”

The National Gallery of Australia (NGA) has partnered with the NGMA for the exhibition. It was presented in Berlin as part of the Australia Now Germany 2017 programme, and is a curtain raiser to the forthcoming festival of Australian culture and creativity in India.

Adwaita Gadanayak, Director-General of NGMA, says, “The display holds lessons for us on how to preserve and focus on our traditional art forms. For instance, the Gond art form of Madhya Pradesh is quite old and unique, but we dismiss all our tribal art forms as ‘craft’.”

The exhibition is at NGMA, Jaipur House, Delhi, till August 26

For all the latest Lifestyle News, download Indian Express App

.png)

Work by Jean Baptiste Apuatimi

Work by Jean Baptiste Apuatimi Meeting the White Man

Meeting the White Man

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario