Tales of Future, Past

Two stories by Intizar Husain that trace the times gone by against the backdrop of Partition

Tales of Future, Past

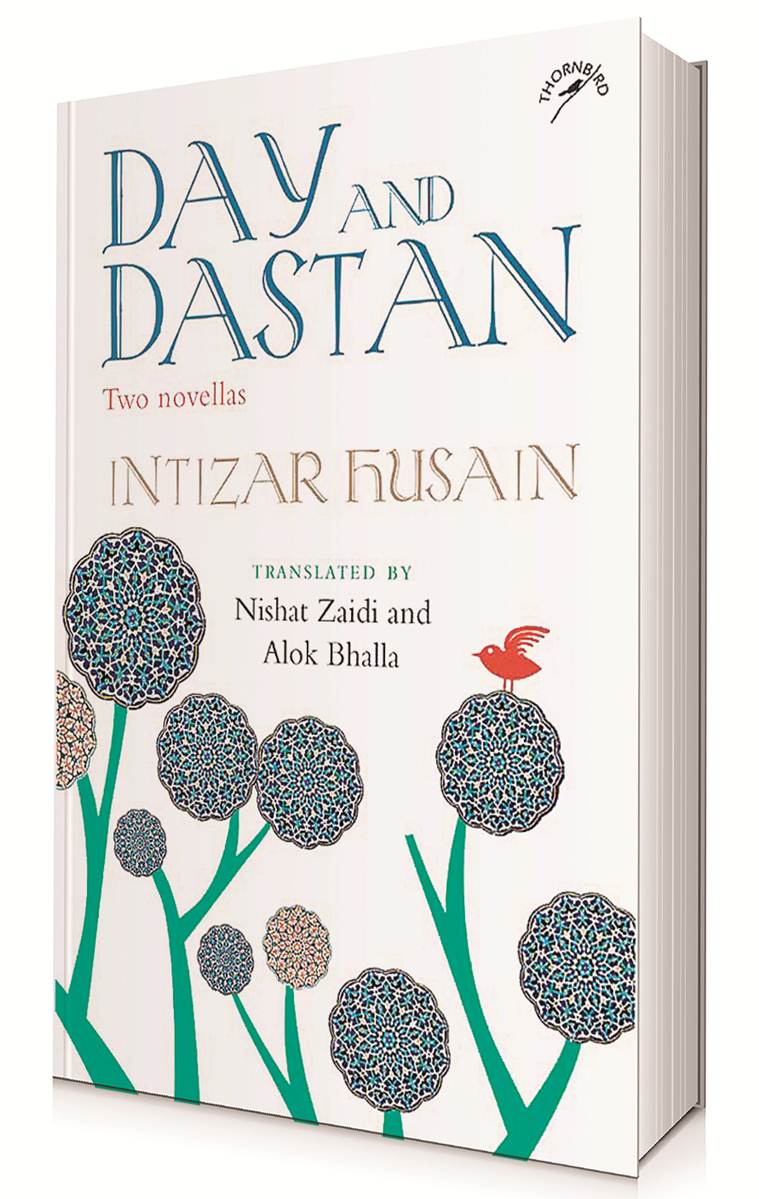

Title: Day and Dastan: Two novellas

Author: Intizar Husain (Translated by Nishat Zaidi and Alok Bhalla)

Publisher: Niyogi Books Private Limited

Pages: 192

Price: Rs 395 (hard-cover)

Author: Intizar Husain (Translated by Nishat Zaidi and Alok Bhalla)

Publisher: Niyogi Books Private Limited

Pages: 192

Price: Rs 395 (hard-cover)

Amongst the finest Urdu writers of the subcontinent, Intizar Husain not only defied classification as a ‘progressive’ writer, he was criticised for his ambivalence, and, later, open break with the more assertive Progressive Writers Movement. In fact, he was criticised more for this breaking away, despite being a product of his times — fully cognisant of the politics and lived realities around him as he wielded the pen. But Husain was determined to deal with politics and its impact on lives in his own way. And like it or not, he wielded his pen in his own distinct manner in his long and illustrious writing career.

His flight from Dibai, in Bulandshahr, Uttar Pradesh, during Partition — when he left with very few belongings, amongst them an Urdu translation of the Bible — is as much known for what he left behind as for what he carried in his head as he made his new home in Pakistan.

But Husain’s stories would, perhaps, be best filed under the section ‘Untranslateable’. Much has been written about the formidable Qurratulain Haider and Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s translations, and, of other doyen of literature. There is always a debate on whether they ever do full justice to their own majestic grasp of original Urdu prose.

But that prose ‘gap’ may appear more pronounced because the reader herself is affected by choosing to read in another language — that is, not reading the original despite knowing the language it has been written in.

However, Day and Dastan suffers less from that charge of linguistic disconnect. In fact, they call out, loudly, to precisely the reader who knows both languages — the one the writer has written in, and the one they have been translated in — and, through these translations, is able to savour both flavours.

A small instance is how, in the description of Zahir and Tehsina’a Abba Mian, the reference to his apparel, the thin muslin kurta, the lazy afternoons with the siesta in the village and enchantingly, the description of the walking stick like the “laam” of the Urdu alphabet which looks like a mirror of the Roman ‘L’. There is a feeling that the translated text has retained elements of Urdu in how it reads, and this is a tribute to both the translators, Nishat Zaidi and Alok Bhalla.

Intizar Husain, in both stories, manages to convey the full range of the worlds he portrays. His references to stories from Hindu mythology have always surprised those who walked into Husain’s work late, and have wondered how it survived his long stay in Pakistan — he had left western UP at a very young age. But clearly, whatever he absorbed in the life around him stayed with him, and his need to suffuse his stories with references of those ideas and Gods is tremendous. At no point does it appear forced or caged in a nostalgic recount.

Conversations that one has had with Husain later in his visits to India have made it clear that he continued to read up and live in the world he had left behind. But more than a lament, it is a testimony to how it moulded his creative process.

The second novella in this book, Dastan, has, for the want of a better word, surreal moments — a character speaks clearly of being forced to leave “the city of my ancestors”, as he rides out, past his family graveyard. The character, of course, has little time for sentimentality near the end, and, despite his eyes welling up, needs to leave in a hurry.

Day and Dastan could be read as a part-nostalgic and beautifully crafted tale of yesterday. But, it speaks loudly too, of the present, and also of the futures foregone as hate and separation tore at lives in 1947.

A sentimental look at the past or a cold reckoner of what must be avoided — the choice is left to the reader: Day or Dastan? Whichever it is to be.

For all the latest Lifestyle News, download Indian Express App

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario