‘Women have had a double battle to fight in South Africa’

Author Zainab Priya Dala on her latest novel set during the anti-apartheid movement, feminist politics in South Africa and her Indian roots.

Author Zainab Priya Dala

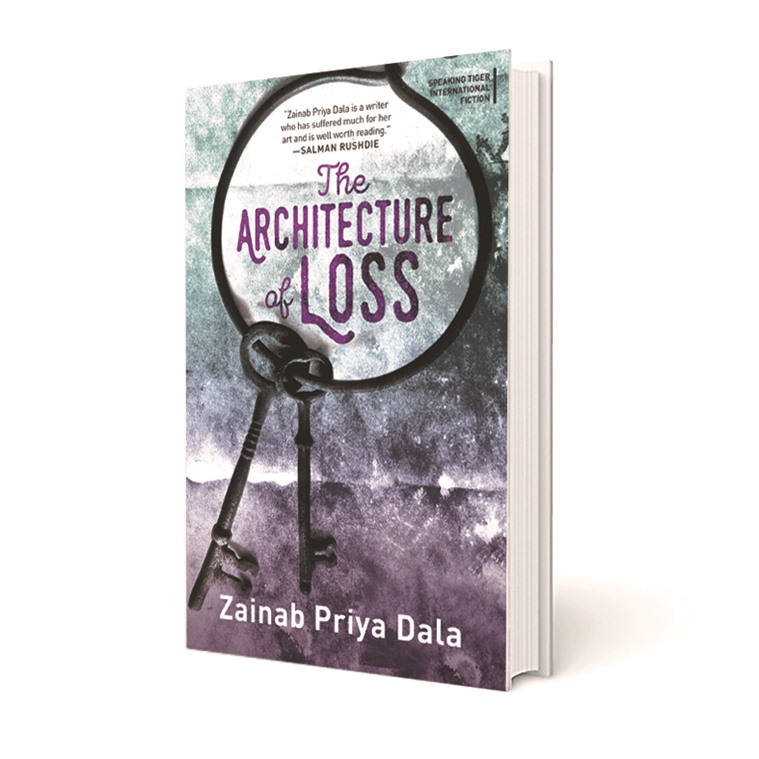

Winner of the 2015 Minara Aziz Hassim Literary Prize in South Africa, author and psychologist Zainab Priya Dala is a third generation South African of Indian origin based in Durban. A victim of an extremist attack after she appreciated author Salman Rushdie at a literary event in Durban in 2015, Dala, 43, has now released her second novel, The Architecture of Loss (Rs 399, Speaking Tiger). A tale of loss and reconciliation, it revolves around Afroze Bhana and her cancer-ridden estranged mother, Sylvie Pillay, who was a fierce activist during the anti-apartheid struggle. Excerpts from an e-mail interview with the author:

You point out that the contribution of women activists was overlooked during the anti-apartheid movement, and that while addressing racism, sexism is ignored. Can you throw some light on feminist politics in South Africa?

Much like the subjugation of people of colour into a form of slavery, women too have been and still are highly subjugated. It is the women in this country who have borne the greatest effects of apartheid. They have had a double battle to fight. The encouraging thing now is that more women of my age are speaking about chauvinism. The feminist movement is at its birthing process. It starts with truth telling, and that is where we are now. Once we stop being afraid to speak out about all our combined challenges and victories as a sisterhood, we can map a way forward for our daughters.

How does apartheid affect you in today’s South Africa?

We are grappling with racism that is still bubbling under the veneer, with new ways to live in a country and in a globalised world, while retaining our cultural Indian heritage. I will outline in my book of semi-autobiographical essays (to be published in September by Speaking Tiger), how the contemporary South Africans, particularly those of Indian descent, are negotiating identity.

In the story, Sylvie dotes on her caretaker Halaima’s daughter, Bibi, and Afroze finds solace in Moomi, her stepmother. What would you say about familial ties?

Sometimes those who are bound by blood may not be the most comforting presence in peoples’ lives. In times of strife or uncertainty, people who comfort us become our family. During the apartheid era, many people forged lifelong relationships with their cadres. During those times, blood families were sometimes split apart by the migrant labour system that took parents away from children.

Can you share more about your Indian roots and the Indian origin South African community?

I am a third generation South African of Indian descent. My paternal great grandfather came from a village near Gorakhpur (Uttar Pradesh) to Durban as an indentured labourer to work on the sugarcane fields, while my maternal family arrived as traders, as did my husband’s family, from Gujarat. There are many layers to South African Indians that most people don’t know about — the system of indenture, its true heart of violence and subjugation, as well as the amazing tenacity of migrant people from India, who have now settled into being a strong yet fragile force in South Africa.

On the cover of the book, novelist Salman Rushdie writes that you have suffered much for your art. Tell us about your foray into writing.

Growing up in apartheid, there were very few opportunities for people of colour to pursue writing. Our literature was confined to what the White government allowed, and we were told “good Indian girls became nurses or typists”. I pushed ahead and wrote my debut novel, and now The Architecture of Loss, and have had them published worldwide. Yet, in South Africa, my books are ignored and the latter was not even published. I live with a label of being outspoken, telling uncomfortable truths in fiction as well as essays, plays and screenplays. But it hasn’t stopped me, nor will it ever.

According to news reports, you were hit on the face with a brick and put into a mental asylum after you praised the writing style of Rushdie at a literary festival in Durban in 2015. Can you tell us more about that?

As a correction, I was not put into a mental asylum. This was irresponsible journalism and I issued a statement via PEN International following the event. Yes, I was assaulted for expressing my admiration for Rushdie’s writing style. The physical assault and head injury gave me severe PTSD, and I went voluntarily into a psychiatric hospital for treatment. I, unfortunately, did not receive very good treatment for my condition and I did not receive any privacy from media and some extremist groups.

What do you have to say about freedom of expression in South Africa?

In the new Democratic South Africa, we have one of the most well-designed constitution documents, which allows for freedom of expression. As artists we cannot abuse this power and need to be responsible in what we put out there as authentic art. While many South Africans respect this, there are those who don’t. This is also true for civil society. We are learning to embrace freedom of expression that doesn’t transgress core values and engage in hate speech or racism. It is a delicate balance because we value dialogue as being open and transparent, but freedom of expression must be handled with sensitivity.

For all the latest Lifestyle News, download Indian Express App

.png)

Cover of the book The Architecture of Loss Mortada Gzar.

Cover of the book The Architecture of Loss Mortada Gzar.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario