Mixed Doubles

An exhaustive account of PN Haksar, who helped steer Indian diplomacy with then PM Indira Gandhi

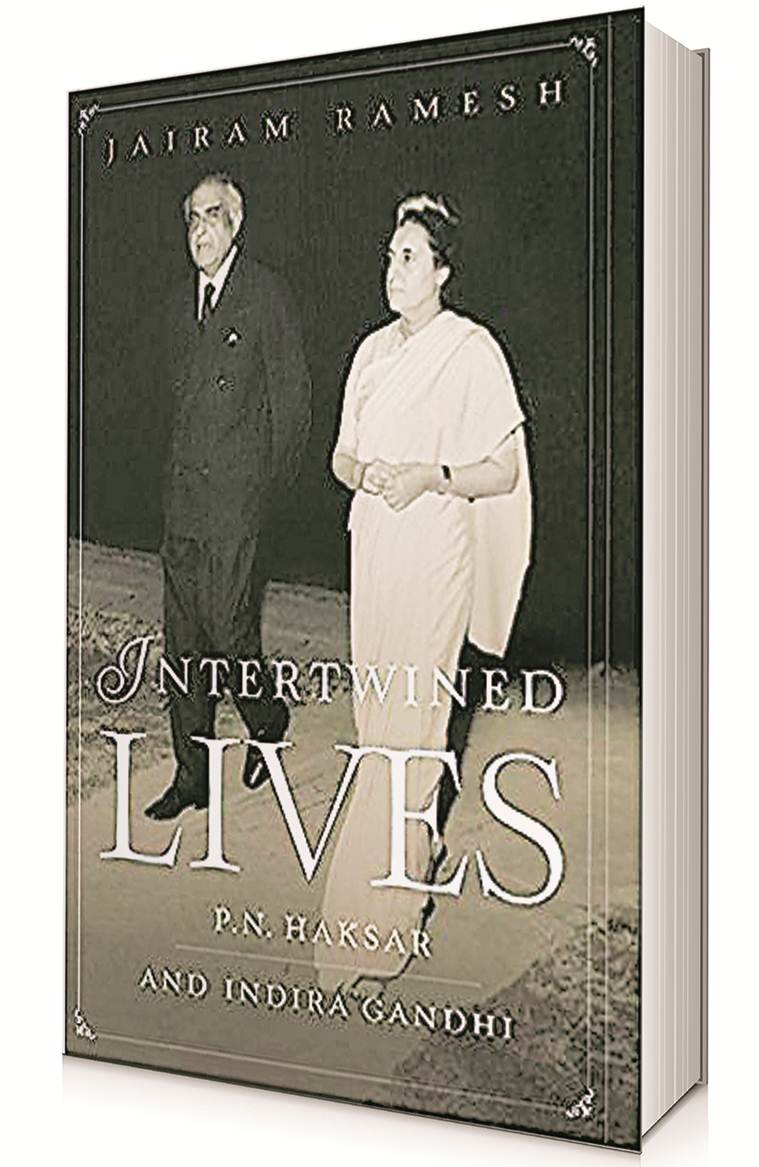

Indira Gandhi flanked by Aziz Ahmed (left) and PN Haksar, New Delhi, August 1973, after signing of agreement between India and Pakistan. Between Indira Gandhi and Haksar are PN Dhar and Foreign Secretary Kewal Singh. (Courtsey: Simon & Schuster India)

A fascinating story about a fascinating man, deeply researched and very readably recounted. PN Haksar was a student of science who blossomed as a master of the humanities. Jairam Ramesh is a graduate of IIT, Powai, who has emerged as a historian of redoubtable ability. Perhaps that is what makes him such a formidable biographer of one so like him, very possibly a future Haksar to a future Prime Minister.

Ramesh has secured access to a treasure trove of private and public papers, mostly available in the Nehru Memorial Library and some in the custody of the family. Apart from delving deep into these archives, he has been relentless in tracking down those who were associated with Haksar to obtain the most penetrating insights into the mind and work of India’s Thomas Moore, the Man for All Seasons.

He has also surveyed the exhaustive literature that lightens up Haksar’s relatively unpromising beginnings — the Board that admitted him to the Indian Foreign Service described him as “average” — to his “Golden Years” (1967-72) as Indira Gandhi’s friend, philosopher and guide, to him finding his nemesis in her quite unworthy son, Sanjay Gandhi, and then his autumnal decline over close to three decades, increasingly blind but available on call when sought, always reflective but never resentful or bitter.

Ramesh points out that Haksar never had anything adverse to say publicly about Indira Gandhi despite the shabby treatment meted out to him, principally because he tried to warn her of the danger to her and her country of letting motherhood undermine her role as India’s leading political personality.

The inflexion point came on 2 February 1971, just weeks before the Bangladesh crisis was to erupt like a volcano, when Indira Gandhi, of her own accord, sent Haksar “an extraordinary note” that contains the wholly personal thought: “Rajiv has a job but Sanjay doesn’t and is also involved in an expensive venture. He is so much like I was at his age — rough edges and all — that my heart aches for the suffering he may have to bear.” (Italics mine). There you have it: the psychological explanation for her defiance of her most trusted confidante, Haksar, leading, in consequence, to the Emergency and its excesses.

What happened to Haksar during his sunset was personal to him; the true heart of Ramesh’s tale is what happened when the sun shone bright on him to the country and the PM he served so conscientiously and so well. A good biographer must never intrude between the reader and the book’s protagonist. The really commendable feature of this biography is that for the most part Ramesh tells the story in the words of Haksar himself — his unpublished autobiographical fragments; his official despatches, minutes and memos; his penetrating reflections and analyses of matters routine and profound in communications addressed to the Prime Minister; and, his recorded notes on conversations with colleagues, friends and antagonists — most tellingly with Kissinger. Ramesh then backs up Haksar’s recollections of events and exchanges with collaborative evidence from others involved at crucial moments in the nation’s life. It is not the biographer who is exultant in times of triumph, it is the record that is exultant, and when the wholly unmerited decline sets in, again it is the record that tells the tale rather than the author’s personal lament. This is not hagiography, but authentic biography.

The chapter everyone will to turn to immediately is the one that deals with Haksar’s role in the liberation of Bangladesh. A detailed account must await the coming publication by Ambassador C Dasgupta who has been researching the Haksar archives more or less simultaneously with Ramesh. Jairam quotes Dasgupta as saying that Haksar was the one who masterminded, “a grand strategy integrating the military, diplomatic and domestic actions required to speed up the liberation of Bangladesh”. Ramesh serves up a delicious hors d’oeuvre to this feast.

Rejecting the advice to the contrary given by the likes of that always over-rated defence expert, K Subrahmanyam, “Indira Gandhi’s priority,” underlines Ramesh, “and that of Haksar was not for a military intervention… Indian military intervention, if needed at all, was to be the last extreme resort after all diplomatic and political means had exhausted themselves”. Haksar argued that no military action could succeed unless there were an insurrection within East Pakistan by Bangladeshi freedom fighters. To this end, “training and arms” may be given by R&AW to the mukti bahini, but the focus must be on securing coherence within the Bangladeshi political leadership; broad-basing it to include as wide a spectrum of unyielding domestic support for liberation as possible; to launch, at the same time, a diplomatic broadside that would inform international opinion of the events leading to the show-down and the ongoing atrocities of the West Pakistan army; and, the huge burden being placed on Indian shoulders by the influx of some ten million utterly impoverished and despairing refugees.

Meanwhile, a diplomatic trishul was devised, principally by Haksar, to deal with three key forces that might have thwarted us: the Soviets who had to be turned around from their temptation to exploit economic and military options with Pakistan by granting Kosygin, the Soviet PM, the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation that he had so long desired; the Americans by firmly turning down their threats and blandishments to go easy on a Pakistan that had just offered Kissinger the opportunity of secretly traveling to Beijing; and, limiting China to “moral support” for their “all-weather” friend, Pakistan. Additionally, there was a touch of John Le Carre with Haksar going off on “pre-retirement leave” to a host of key capitals over six weeks from 5 September to 25 October. Ramesh suggests: “There was definitely some super secret diplomacy going on”.

Victory for Indira Gandhi and Haksar was complete but within a year their “intertwined lives” unraveled. Alas!

The writer is a former Congress MP

For all the latest Lifestyle News, download Indian Express App

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario