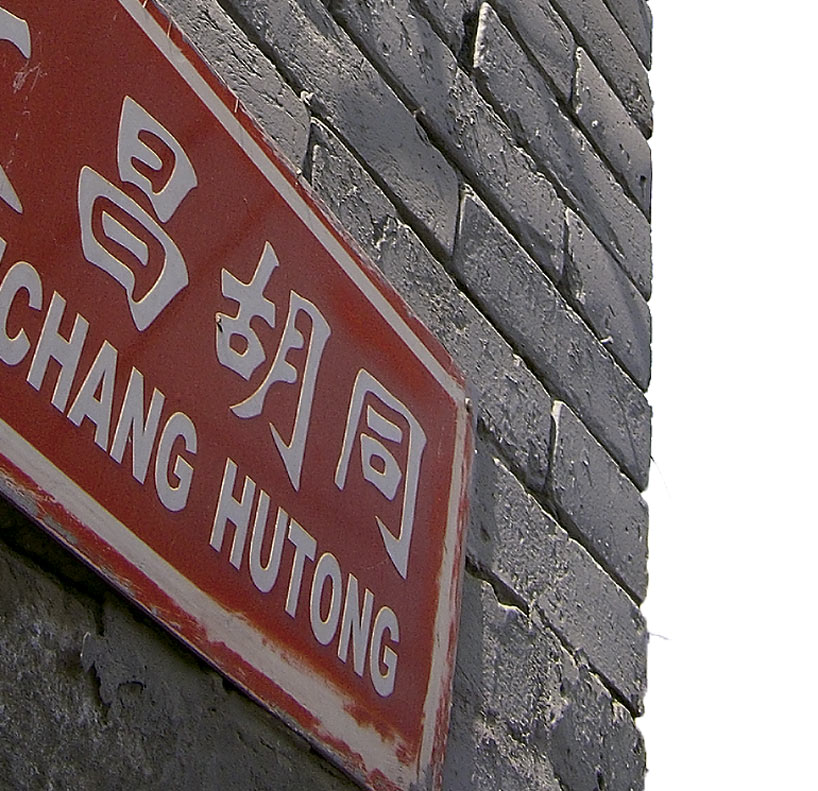

The hutongs of Beijing

The word hutong, meaning a narrow street or lane, is unique to northern China. The grid of hutongs crisscrossing Beijing has shaped both the city’s neighborhoods and the city itself. Today the hutong is the lens through which many people experience life in Beijing. Many know that the Great Wall is visible from the moon, but few realize that the length of Beijing’s hutongs put together is longer than the Great Wall.

Just how many hutongs does Beijing have? One old saying goes, “there are 360 famous hutongs, and as many unknown hutongs as there are hairs on an ox.”

Zhu Yixin’s Records of the Capital’s Alleys and Lanes, written during the Qing Dynasty, lists 2,077 hutongs, with 978 actually bearing the word hutong in their name. In 1944, Japanese author Tada Teiichi recorded in Beijing Place Names that Beijing had 3,200 hutongs (including streets and alleys without the word hutong in their names). The Comprehensive List of Beijing Street and Alley Names, published in Beijing in 1986, surveyed ten city districts including Dongcheng, Xicheng, Chaoyang, Haidian, and Mentougou, and lists a total of 6,104. Many know that the Great Wall is visible from the moon, but few realize that the length of Beijing’s hutongs put together is longer than the Great Wall.

The word hutong, meaning a narrow street or lane, is unique to northern China. The first recorded use of the word comes from noted Yuan Dynasty playwright Guan Hanqing’s Meeting the Enemy with a Single Long Broadsword. Modern scholars cite four possible origins of the word:

- An evolved pronunciation of the term houtong (literally‘passable through back ways’).

- The pronunciation of hutong is similar to the Mongolian and Manchurian pronunciations of the word for ‘well’. Most Beijing residents got their drinking water from wells in that period, so wells became natural gathering places and focal points for neighborhoods, so over time, the word became another word for ‘alleyway’.

- In the Yuan Dynasty, Mongolians referred to cities and villages as haote, a pronunciation which later evolved into huonong and nongtong, and finally became the localized terms for ‘lane’or ‘alleyway’ we see today in hutong (Beijing) and nongtang (Shanghai).

- Still others believe the term hutong is a shortening of the Yuan Dynasty political slogan “hu ren da tong” (the Hu people unify and govern the nation).

No matter where the term originated or how it was passed down to us, today the hutong is the lens through which many people experience life in Beijing.The grid of hutongs crisscrossing Beijing has shaped both the city’s neighborhoods and the city itself.

And in many ways, the hutong is more than just an architectural concept to Beijing’s residents. It’s become synonymous with eras past, memories, and the feeling of home.

The form of Beijing’s hutongs has changed, developed, and evolved with the city. Far more than just the veins in which the city’s traffic flows, they are living records of historical and stylistic changes.

In the introduction to her novel The Song of Everlasting Sorrow, Wang Anyi spends two entire chapters describing Shanghai’s nongtangs. Similarly, in Beijing there seems to be an endless stream of TV series like Small Well Lane (Xiaojing Hutong), which, alongside the films and literature that explore the same subject, enjoy surprising popularity.

Among the films released during 2016’s Lunar New Year box office season was Mr Six, which many worried would perform poorly thanks to its heavy use of Beijing dialect (jingpian’er). But good movies transcend the limits of region and language. On its fifth day in the cinema, Mr Six ticket sales reached 50.5 million RMB, setting a new record for single-day box office sales in China, and praise of the film was almost universal. The Beijing represented by the main character is the Beijing of the hutongs, and while hutong culture might feel dated to today’s audiences, it’s also full of connotations of humanity, friendship, and loyalty.

The short film 100 Flowers Hidden Deep directed by Chen Kaige was one of the 15 episodes of the Ten Minutes Older collection of shorts. Set in Bai Hua Shen Chu Hutong ‘Deep in One Hundred Flowers’, the film allows us to share the same affection Beijingers feel for their hutongs. Writer Lao She described Bai Hua Shen Chu Hutong as:

A long, narrow alley, lined on both sides by walls of broken-down bricks. The south wall rarely sees sunlight. It’s covered with a thin layer of green moss, and higher up the wall you find the silvery trails left by passing snails. As you proceed down the lane, it seems to widen, but the state of decay in the brick walls seems to worsen as well.

Gu Cheng, in his poem A Eulogy of Deep in One Hundred Flowers, says:

Deep in One Hundred Flowers is a treasure

Its beauty unknown to an outsider.

Half in shade is the courtyard houses’ wall

With the grass in the old temple three-foot tall.

Never forgotten by the autumn breeze

Blowing off the yellow leaves of ginkgo trees.

This place surpasses the Peach Blossom Utopia

Pity its residents age and their sunsetis near.

Its beauty unknown to an outsider.

Half in shade is the courtyard houses’ wall

With the grass in the old temple three-foot tall.

Never forgotten by the autumn breeze

Blowing off the yellow leaves of ginkgo trees.

This place surpasses the Peach Blossom Utopia

Pity its residents age and their sunsetis near.

Not far from Deshengmen Inner Street is Sanbulao Hutong ‘Three Not Olds Alley’, a place of significant importance in the childhood memories of poet Bei Dao. He describes his years as a student while living at No. 1 Sanbulao Hutong: “My three years of middle school passed quietly under the swaying branches of the old Chinese scholar tree by the entrance of the alley.” A short way up Sanbulao Hutong is No. 6, where Ming Dynasty maritime explorer Zheng He, who explored the “Western Oceans” (the south Pacific and Indian Oceans), kept his official residence. During the Ming Dynasty, the alley was known as “Sanbao Laodie Hutong” (literally ‘Sanbao Old Father’s Hutong’ or “Sanbao Hutong”. The two characters “Sanbao” meaning ‘Three Treasures’ in reference to the “three jewels” (triratna) in Buddhism, were one of Zheng He’s childhood nicknames. During the Qing Dynasty, the name was changed to “Sanbulao Hutong”, and referred to as either “Sanbulao” (literally ‘Three Not Olds’) or “Sanbolao” (literally ‘Three Old Uncles’) colloquially.

But Sanbulao Hutong isn’t the only hutong with a name derived from famous figures. Wudinghou Hutong was the residence of court official Guo Ying during the Ming Yongle’s reign, and in Wangjia Hutong was located the residence of favored court official Wang Youguo during the reigns of Yongzheng and Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty. Similar old buildings, historical events, and famous historical figures can be found down almost every hutong.

There’s a group of red brick buildings in the eastern portion of Sanbulao Hutong that was once a gathering place for cultural luminaries. Just like Republic-era Shanghai, in Sanbulao Hutong figures like Xu Ying, Zi Gang, Feng Yidai, and Huang Zongying made their homes here. Crosstalk legend Hou Baolin also lived here as a child.

Dayabao Hutong was another hutong renowned for the pioneers of modern art who clustered there. Immediately recognizable names like Li Keran and Zhang Ding were once residents, as well as Dong Xiwen, who gained his fame for painting The Founding of the Nation, and his son Dong Shabei, and many more.

“Mr Six, there is no Xuanwu District. It was folded into Xicheng.” This casually inserted line from Mr Six actually solicited loud boos from audiences. As the city develops, new buildings and construction projects mean the hutongsare slowly disappearing. In Shower , directed by Zhang Yang, the hutong where the story takes place is about to be demolished. The bathhouse owner’s son stands in the empty shower area and sings a final elegy for the soon-to-disappear hutong.

But, there are also many people racing to the hutongs in order to protect them and working to save what remains of hutong culture. Young entrepreneurs are opening shops, restaurants, and bars with a creative focus in the hutongs, bringing fashion and the ethos of cool to the old lanes. In city development plans the government is also paying attention to preserving hutongsand protecting the old buildings they contain, with some areas becoming focal points for local tourism.

A heavily Beijing-flavored song puts it best, “My grandfather played here when he was young, and the towering Qianmen Gate seems like it’s next to where I live.” For old Beijingers who’ve lived here for generations, the courtyard houses (siheyuan) and hutongs are anchors for their memories and dreams. As the city grows and reshapes itself, and as people move into modern apartments, relationships with neighbors and the appearance of the city will undergo many changes. While the hutongs and the memories they contain slowly fade into history, these alleys which birthed Beijing’s culture will linger in our hearts and minds.

Published in Confucius Institute Magazine

Published in Confucius Institute MagazineMagazine 43. Volume 2. March 2016.

View the PDF print edition

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario