1001 Cures: Translation Movement

by Peter E. PormannPublished on: 27th September 2019

Translation is one of the most powerful drivers in the development of science and medicine. From the earliest periods of recorded history until today, translation has played a crucial role in propagating scientific knowledge.

In the early period of Graeco-Arabic translation movement, Syriac translations often served as an intermediary step in the transmission from Greek into Arabic. The first aphorisms of this copy of Hippocratic Aphorisms in Syriac and Arabic says that ‘life is short, the Art long, opportunity fleeting, experience dangerous, and judgement difficult.’

The Greeks drew on the know-how of the Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilisations, to which they had access through a process of both oral and written translation; a wonderful monument to this transfer from Ancient Egyptian into classical Greek is the famous Rosetta Stone, which contains a decree by the Ptolemies in hieroglyphic, demotic, and Greek. Likewise, Roman culture drew heavily on Greek sources and developed its own medical language through translation. For most of the medieval and early modern periods, Latin was the lingua franca in which medicine was taught, discussed, and written about throughout Europe, and it was only through a long process of translation that medical knowledge became accessible in various European vernaculars such as German, French, English, and Russian. Even during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, translations between these vernaculars furthered knowledge transfer and helped promote scientific research and progress. In the early twenty-first century, English emerged as a new scientific lingua franca, playing a similar role to that of Latin during the Middle Ages or Greek in Antiquity.

13th-century manuscript showing a Greek translation of the medical handbook by Ibn al-Jazzār entitled Provisions for the Traveller and Nourishment for the Sedentary (Zād al-Musāfir wa-qūt al-ḥāḍir), known in Greek as Ephódia toû apodēmoûntos. The handbook was first translated from Arabic by Constantime the African (d. before 1099).

Arabic also emerged as a lingua franca of scientific exchange during the medieval period as a result of the famous Graeco-Arabic translation movement. On the shores of the Guadalquivir and the Ganges, physicians wrote medical treatises in Arabic. Even in early modern Europe, there was a clear sense that Arabic was the language of science par excellence. For this reason, the Franciscan Friar Roger Bacon (c. 1214–92) advocated the study of Arabic, and John Selden (1584–1654), a prominent lawyer, historian and linguistic scholar, said that ‘the liberal and correctly taught sciences were for a long time called by us ‘the studies of the Arabs’ or ‘Arabic studies’ (Scientiae Liberales ritèque institutae, diù ante vocari solebant a Nostris Studia Arabum & Arabica Studia)’ (quoted in Pormann 2013a, 73). Dimitri Gutas (1998, 8), who studied the Graeco-Arabic translation movement in detail, rightly likened it to classical Athens or Renaissance Italy in importance and impact. What then was this great movement that so profoundly shaped the fates and fortunes of countless human beings?

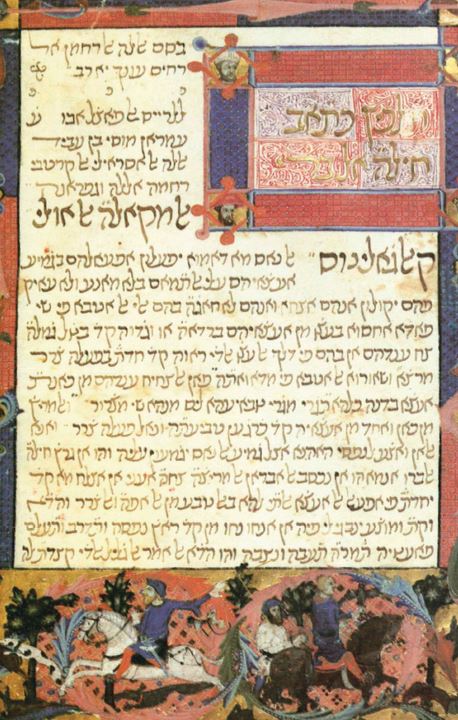

Opening of Maimonides’ Abridgment of Galen’s ‘Method of Healing’ in Judaeo-Arabic, that is, Arabic written in Hebrew. The text begins with the basmala ‘In the name of God, the merciful, the compassionate (Bi-smi llāhi l-raḥmāni l-raḥīm)’.

From the second half of the eighth to the first half of the tenth century, the majority of Greek works read and studied in late antique Alexandria were translated into Arabic. These translations included not only philosophy (e.g. Aristotle, Plato, Plotinus, Porphyry), mathematics (e.g. Euclid), astronomy and astrology (e.g. Ptolemy), medicine (e.g. Hippocrates and Galen), engineering (e.g. Hero of Alexandria), but also some popular philosophy (gnomological collections) and literature (e.g. the Alexander Romance, Menander one-liners). For the sake of convenience, one may divide this translation movement into three periods: 1) an early one in the late eighth century when a technical vocabulary had not yet been established; 2) the heyday in the mid-ninth century; and 3) a later period in the early tenth century. The two main groups of translators during the second period coalesced around al-Kindī, the so-called ‘philosopher of the Arabs’ (c. 801–66) and Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq (c. 808–73), respectively. The later period is chiefly associated with a group of Aristotelian philosophers in Baghdad who gathered around al-Fārābī (d. c. 950). In the following, I shall focus on Graeco-Arabic translations of medical texts during the first and second periods…

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario