At the Top of his Game

Crime fiction writer Surender Mohan Pathak on the changing genre of crime writing in India, the lack of opportunities for Hindi writers, and the ease of getting published in English

Written by Arti Chouhan | Updated: October 6, 2018 12:30:15 am

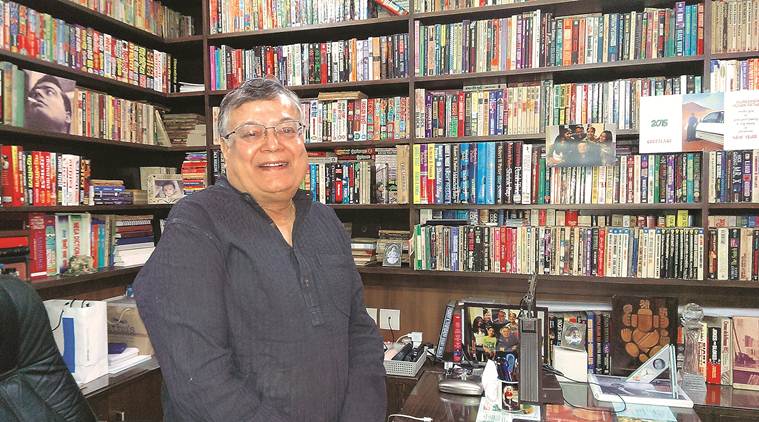

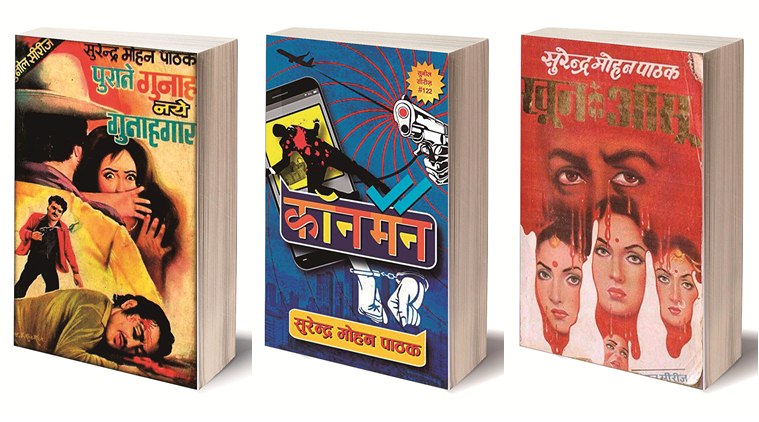

Surender Mohan Pathak; book covers of his crime fiction novels

Surender Mohan Pathak always shows his fans and admirers the permanent dent in his middle finger which is the result of continuous writing for years. Often referred as the emperor of crime and mystery genres, Pathak, still writes with an ink pen. Even at the age of 79, he cannot imagine not writing or reading. “I am always working on a book. I dread the day when I will be without an idea good enough to be transcribed on the paper,” says Pathak, who has 300 books, short stories, joke books and nouvellas to his credit.

The crime fiction writer, who attended the Pune International Literary Festival last weekend, began his writing career with ‘fillers’ for authors who could not make the quorum of the pages decided by the publisher. But readers would rarely notice there was a short story at the end of the book, which frustrated him. It drove him to write his first mystery story — 57 Saal Purana Admi — which had an element of the supernatural, for Manohar Kahaniyan, a monthly magazine published from Allahabad, then the most famous one of this genre. To his surprise, it got published. Encouraged by it, Pathak wrote his first full-length mystery novel Purane Gunah Naye Gunahgaar in 1963 after which he says the ball was set rolling.

But unlike even mediocre English authors who find fame at their footstep by the second or third novel, it wasn’t until his 146th book Khoon ke Aansu that he had publishers lining up outside his door. He would meet them on Sunday, the only time he got the day off from his government job. “By then I had already put in 21 years of whodunits. Khoon Ke Aansu was the fourth and concluding part of a four-part-novel and it took the trade by storm. It’s success earned me a loyal readership,” says Pathak.

Most of Pathak’s work can be categorised in five different series with major work falling under the “Sunil Series” based on a central character Sunil who is an investigative journalist, the philosopher detective Sudhir Kohli on whom 22 novels are based or the “Vimal Series”, which remains his most popular where the hero of the series is a wanted criminal. The king of pulp fiction, his novels are focused on murder mysteries and crime thrillers. At least two criminal cases — the Tandoor scandal in Delhi, where a man tried to dispose a corpse in a furnace, and a robbery at UTI Bank Vikaspuri where a man pretended to be a human bomb — are said to have been copied from his novels.

For someone who has seen crime writing evolve in the country, he says the genre has become immensely popular. “Every new writer comes with a mystery novel to be published, and it is more so in English. Hindi is far behind in this matter. In four decades, from the ’60s to ’90s, there was many publishers in the Hindi-pocket-book trade and many more writers of this genre to cater them. But after the ’90s, it saw a decline. Most of the publishers shut shop and writers faded into oblivion. This downwards trend has not stopped even today. Currently, finding pocket book publisher isn’t easy,” says Pathak.

There is also a dearth of publishers for Hindi mystery writing he says. “Where will a Hindi mystery writer come from if there are no outlets to publish him? And if he does get a story published, he often does it as his own expense. The little patronage that Hindi enjoys is only in the language belt of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Bihar, while English rules the roost from Kashmir to Kanyakumari and from Kutchh to Kamrup,” he says.

Like most Hindi writers, he does feel the pinch of the luxuries afforded to his English-writer counterparts. “It is much easier to get a book published in English. An author in English gets in the trade through an agent and it is the agent who does all the scouting around. In Hindi there is no such system. For an author who writes in Hindi, the first step is to get his book published and if the book has any merit and the author does write consistently well, the recognition comes. This process is easier in English because patronage of English authors is more vast when compared to Hindi. Also, a Hindi writer is lucky if he is paid at all. Find me one Hindi author who can run his household on his royalties. Barring Gulshan Nanda, there is no Hindi author, and there never was, who can even come close to English authors,” says Pathak.

And the discrimination can be seen at the festivals as well. Pathak shares how a novice author, who has written one book in English and is not likely to write ever again, is an honoured guest at literary festivals but writers like him are not extended the same courtesy. Sometimes, it’s the reader’s bias too. “Have you ever seen a passenger in a flight reading a Hindi book? And the answer is ‘no’ because he would be taken as a ‘backward’ person. Hindi is read in toilets or in the second class, unreserved bogey of a train.”

Pathak recently launched the first volume of his three-part autobiography Na Bairi Na Koi Begana. He admits he was not keen on writing this one but agreed because his editor at HarperCollins insisted. Though unsure of writing not more than 50 pages, he ended by with 600 sheets, equivalent to 1,000 printed pages.

.png)

Crime fiction novels by Surender Mohan Pathak

Crime fiction novels by Surender Mohan Pathak

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario