Between the Lines

A lookback at the life and times, poetry and prose of Shahryar, and the journey of Urdu-Hindi poetry in Aligarh Muslim University

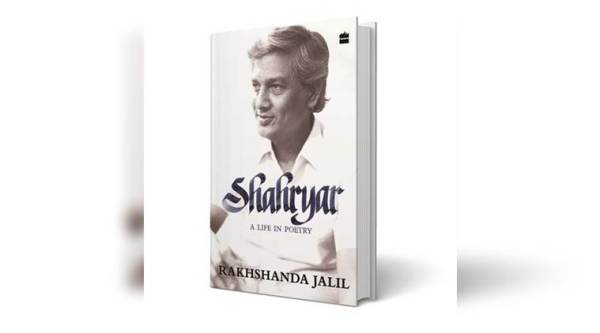

Shahryar: A Life in Poetry Rakshanda Jalil HarperCollins India 256 pages

Ajeeb saneha mujh par guzar gaya Yaaron/ Main apne saaye se, Khud aaj darr gaya Yaaron

Based in Aligarh, the acclaimed poet Akhlaq Mohammad Khan ‘Shahryar’ was deeply connected to the city and the university. His contemporary, the late Kamleshwar, described Shahryar’s poetry as bheegi rait — wet sand. His poetry, Kamleshwar said, lacked the “smoothness of silk or satin or the coarseness or crispness of cotton” and, instead, was like wet sand that bore the weight of meaning. It did not allow one to wring out all meaning but gave a sense of the depth of the deep river or sea that flowed past. But to most Indians, Shahryar would be known for his landmark songs in Hindi cinema, even though he wrote so few. But what he wrote for just Gaman (1978) and Umrao Jaan (1981) was enough to guarantee an instant flicker of recognition from Hindi film music fans of all generations over the years. Shahryar refused to do more film music and while captivating, his repertoire of film songs does not do justice to the full breadth of his reputation as a poet. It does not even bring all the colours and flavours of his poetry to the screen. Contrast this with his fellow Aligarh poet Neeraj, who died recently. Like Shahryar, he wrote less, but managed to get his film work to reflect his book of poems. Not so, with Shahryar. Shahryar’s poetry, prose and life are brought together very interestingly in Rakshanda Jalil’s latest work, Shahryar: A Life in Poetry, a valuable addition to the long list of books by her on Urdu poetry and its poets.

The book is aimed at both those who already know something about Shahryar and those who know just enough to appreciate how little they know. Shahryar, a stylish and modern poet, was a special voice of his time. He was unique in his ability to steer clear of both the labels popular at the time: of being progressive (taraqqi-pasand) and modern (jadeedi). His poetry singularly lacks lines such as those that Faiz, Firaq or Jalib wrote, which served as calls for action. Yet, maintaining that he was a Marxist (though not an atheist) Shahryar was modern, keen to speak “to the people and of the people” and to not get trapped into just romantic and nostalgic concerns. Most of all, he was comfortable to not be labelled as either. Jalil has dwelt on the parallel movements in Hindi and Urdu poetry of the time between the progressives and the modern camp, and, the unique trade-offs between belonging to either ‘camp’, not to mention the limitations it drew around him. Shahryar’s subtlety is brought out through an interview with Gulzar, who says categorically that Shahryar was modern, but a small-town modernist, “not a New Yorker… he spoke of Ghantaghar, not of the Eiffel Tower.” Shahryar seldom spoke of overt political events and, even while delving deep within, hardly wrote of things that could be connected back to personal happenings or his own circumstances. His popularity perhaps emanates from his ability to make “common cause” with his readers and while almost aloof, not making it ‘personal’ or exaggerating, being able to get through to the heart of the human condition. Shahryar’s bold and direct sketches of physical intimacy and longing also marked him out as a poet, something that this book brings out very well.

But beyond just the one poet, Shahryar: A Life in Poetry must be commended for bringing to light much about Urdu and Hindi poetry, and its journey in Aligarh Muslim University. The author tackles some thorny issues effectively, all in the course of describing Shahryar’s life and times; like how much the self must be central for a poet and how much the world or the times, for a piece of writing to be a classic. The poet’s commitment to form and respect for poetic tradition is also brought out. Shahryar believed that discipline or studying the craft of writing poetry is as important as talent: “Everyone cannot marshall the ideas produced by their imagination, organise them in a coherent and meaningful manner and present them in a way that is pleasing or new. Nor can everyone gather together scattered ideas and thoughts in a way that is startling. The primary function of any art form is to surprise; it is the most magical effect that art can produce.”

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario