Sita’s new world

Walikhanna charts the journey of Indian women from birth to childhood and adolescence and marriage, and their experience of gender-based violence.

In the book, Charu Walikhanna imagines Sita as a visitor to contemporary India.

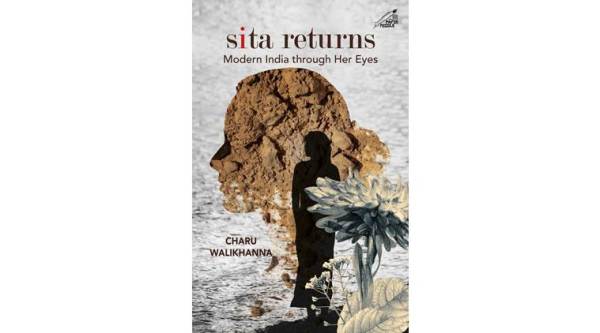

Title: Sita Returns: Modern India Through Her Eyes

Author: Charu Walikhanna

Publisher: Niyogi Books

Pages: 310

Price: Rs 495

Author: Charu Walikhanna

Publisher: Niyogi Books

Pages: 310

Price: Rs 495

Like all foundational epics, the Ramayana is a tangible presence in contemporary Indian life, renewed with retellings, performance and prayer. Its characters turn up in daily conversations and political debates (the laughter of a woman MP in Parliament being likened to Surpanakha’s cackling recently). The birthplace of Ram is at the heart of a legal battle that has divided the country for over two decades. It’s no wonder, then, that Sita also offers a way to examine the life of Indian women today.

In Sita Returns: Modern India Through Her Eyes, Charu Walikhanna attempts just such an exploration. She imagines Sita as a visitor to contemporary India. Walikhanna teases out the parallels and divergences between Sita’s story and the challenges women face. She begins with the charmed story of Sita’s ‘birth’ — a foundling who was discovered by a king tilling the earth. As she surveys the stories of infanticide and female foeticide, Sita wonders if she could have been one of the millions of “missing women”. In the stories of sexual assault and violence, and social ostracism of rape survivors, she finds her experience reflected back.

What else does Sita see when she travels India? A country that has enshrined the greatest freedoms for its women in the Constitution but where the reality festers with misogyny. Walikhanna charts the journey of Indian women from birth to childhood and adolescence and marriage, and their experience of gender-based violence. Sita is shocked by the violence done to little children, and the ways in which families stymie their girls, but heartened by stories of sports heroes such as Geeta Phogat.

This is an interesting prism to use, but the narrative suffers from too literal an interpretation. The transitions from the epic to the accounts of discrimination — buttressed by government statistics and ministerial statements — are jerky and awkward. One often gets the sense of having waded into the oped pages of the day’s newspapers. Walikhanna is meticulous in leaving nothing out — from debates on female foeticide to triple talaq and marital rape (Sita appears to think a law on it would not be too wise) — and that conveys an urgency of ticking all the boxes. But no one aspect is explored with detail, nuance and thoroughness. Nevertheless, to bring Sita and contemporary India into a conversation about women’s rights is an exercise worth appreciating.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario