The Dying of the Light

Feroz Rather’s debut collection of short stories is a record of humanity in a place where very little of it survives.

The Night of Broken Glass breathes emotions into this vacuum, colouring between the lines of often unfeeling reports to bring the war-torn state to life.

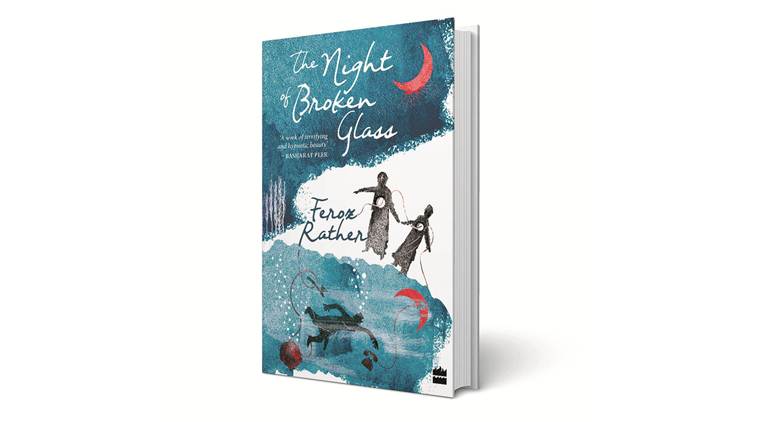

Book: The Night of Broken Glass

Author: Feroz Rather

Publisher: HarperCollins India

Page: 222

Price: Rs 399

For the many people not connected to the struggle within its borders, it might be accurate to say that Kashmir remains an enigma. This, despite the many hours of footage and mountains of newspaper clippings that piece together a history of violence, fear and bloodshed. The Night of Broken Glass breathes emotions into this vacuum, colouring between the lines of often unfeeling reports to bring the war-torn state to life.

Through the course of 13 short stories, Feroz Rather’s book opens brief windows into the lives of people in Kashmir, providing snippets of experience that can almost always be universalised. The stories are rather unusual, in that many of the characters continue to make appearances through the eyes of each other, giving the sense that everything is experienced as an interconnected whole by the community; that every emotion is rooted in the very soil they live on.

It begins, rather pointedly, with an exploration of revenge. In ‘The Old Man in The Cottage’, the narrator finds himself in a position to exact revenge on Inspector Masoodi, who tortured him years ago. Facing the now decrepit and wheezing policeman, the short story examines with chilling detail the range of emotions faced by the narrator, who now has complete power over the oppressor from his past. The tale sets a tone of brittleness and contemplation that is sustained throughout the rest of the book.

The fragile nature of power is a leitmotif, one that Rather explores diligently from a number of perspectives, including from the point of view of the oppressors. His characters are shopkeepers, journalists, labourers — in a word, just ordinary people. They are set apart from millions of others in the way their peace is shattered at a moment’s notice, turning them from anonymous faces to names and faces on news reports within seconds. Oftentimes, it is at the expense of their dear ones or their own lives. Fear, anger, helplessness and rebellion permeate everything from the Revolution cigarettes that so many people smoke, to the students who turn stone throwers because of the sheer intensity of what they feel (‘The Stonethrower’).

In its examination of conflict, the book does not neglect the insidious way internal conflict can tear people apart just as well as external forces. The Syed-Sheikh caste conflict, for example, is examined in detail in ‘Rosy’. As the first-person narrator rails out with passion at one point, “I want to burn down the edifice of the whole damn society who believes that your soul is black dirt because you are a Sheikh while mine is made of white and gold feathers because I am Syed.”

A particularly impressive aspect is that the “villains” of his stories are always detailed, without the predictable redemptive elements that often null their impact. The inspectors — Masoodi, Major S and other haunting spectres of the short stories — are never given an easy way out; the author reaches for no two-line reasoning of why they became who they were. Over the course of the book, he dissects aspects of them and lays them bare for readers to see.

The best example of this is, perhaps, ‘The Nightmares of Major S’. As a man who tortured and terrorised countless people as part of his “duty”, he haunts stories as a name long before the author decides to shine the spotlight on him. The terror he sees in the eyes of the people he tortures soon grow within him, leading to increasingly erratic behaviour and failing relationships. Everything about his perceptions and experiences makes sense, in a grim way, especially with Rather being careful not to let explanations turn to excuses.

The issues with Rather’s debut book are largely technical. One of the book’s pillars of strength is its ability to immerse its readers in the sights, sounds and smells of Kashmir. However, this is by no means a consistent feat as the language turns clunky in parts, becoming less evocative and more puzzling. However, they are never anything more than brief lapses before the prose re-exerts its lyrical hold. There are also less successful executions of intriguing concepts. One such tale is ‘A Rebel’s Return’, in which a ghost hangs around in the basement of Inspector Masoodi’s house. The story attempts to showcase, among other things, the way violence has turned into a vicious cycle, stealing innocence and replacing it with abuse. While the surrealist elements make for an interesting change of pace, the tale itself never fully connects, though it conveys enough of the underlying idea to act as a competent part of the book.

Ultimately, the book isn’t memorable because of its imagery, lyricism or craftsmanship. It lingers because it is a record of humanity set in a place where very little of it survives. Despite this, when the curtains fall on the final act of the final story of the book, the readers are left not with a scene of hatred, but with an embrace. It chooses to treasure a moment of happiness despite having spent the last couple of hundred pages examining just how fragile such an emotion can be. As Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel said, “For in the end, it is all about memory, its sources and its magnitude, and, of course, its consequences.”

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario