The Tapestry of Hope

With loads of Dhakai jamdanis on their back, weavers from Bangladesh visit India every year, aiming to make profits during Durga Puja

Written by Ankita Bose | Published: October 11, 2018 1:57:40 am

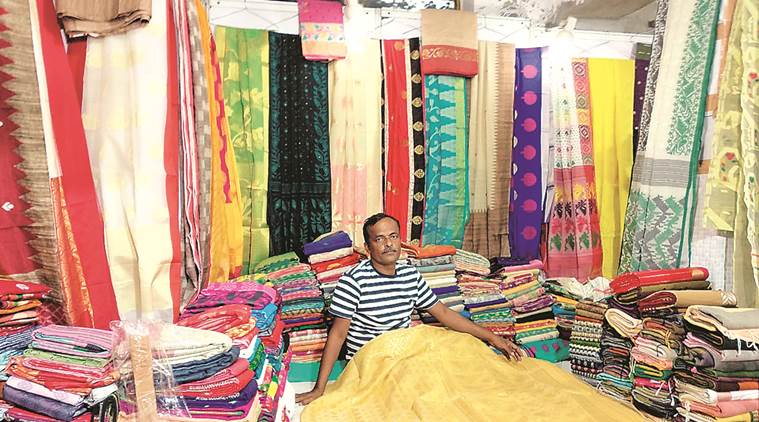

The stall by Habibullah Rahman at Delhi’s CR Park (Source: Ankita Bose)

An original Dhakai Jamdani sari makes its way to India on the backs of those who weave myriad designs on the sheer muslin fabric. Every year, weavers from Bangladesh visit India to showcase their art at local fairs held during the Durga Puja days. At one such fair in south Delhi’s Chittaranjan Park Bangiya Samaj, Muhammad Abir Khan stands out as the youngest but most enthusiastic Dhakai seller. Khan, a resident of Dhaka’s Maniknagar, spent his 26th birthday while crossing the border from Bangladesh to India. With almost 20 voluptuous bags in tow, he and his four companions guard the precious cargo with their life. His father has been touring India for 12 years and he has also accompanied him for eight years now.

“When we travel, I make sure these saris get my own version of first-class travel experience, and get better seats than I do. I clutch the bags to my chest as I travel every year to India, hoping to gain a 10 per cent profit or else it’s really difficult to justify these trips. Back home, no one thinks weaving is profitable anymore,” Khan says.

With a new company of his own that he started four years ago, Khan holds on to the hope of a brighter future. “After all, this is our heritage. Bangladesh is famous all over the world for its Dhakai and its ilish (hilsa). Both are synonymous with Dhaka,” he says.

However, for 58-year-old Habibullah Rahman, age and experience have weathered that enthusiasm. “I’ve been coming to CR Park since 1998. Profit has never been in our hands, so we just hope to at least break even. About 10 years ago, we used to get 145 Bangladeshi taka for Rs 100. Now, since the decrease in value, the conversion for Rs 100 is around 110 taka. This year, the expenses just keep piling on. The organisers have prohibited us to sleep in the stalls. So most of us have had to arrange for last-minute accommodation. Those who can’t afford to do it, sleep in the nearby temple,” he says. The exhibition is on till October 13.

Talking about weaving Jamdani saris is the only thing that lights up 35-year-old Mehdi Hasan’s eyes. But as much as he would love to hold on to tradition, Hasan has had to compromise in order to appease his customers. He said, “The designs take shape in a weaver’s mind and we’ve trusted their instincts for decades together. But what do we do when a customer complains that our designs are basic. We try to innovate as much as possible, but sometimes customers say we don’t try too hard to come up with ‘interesting’ designs and that’s what scares us the most. What if the younger generation is no longer keen to buy Dhakai?”

His concerns are shared by Rahman and Khan, who lament that with every passing generation, fewer people show genuine interest in weaving. More losses than profit and hard labour are what you sign up for when you decide to choose to weave as a profession. “Why would someone sit on the floor in the heat for a meagre wage when you have the option to sit in air-conditioned rooms, and get to take home a better salary?” Khan adds.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario