Earth to Earth

Confrontations with the inevitability of death shape the works in Yardena Kurulkar’s show in Mumbai

Yardena Kurulkar

Nearly a decade ago, when Yardena Kurulkar read the 1965 anti-war classic Slaughterhouse-Five or The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death, she was struck by the casual manner in which Kurt Vonnegut addressed death in the novel. She says, “Vonnegut repeatedly uses the phrase ‘so it goes’ in this book, which follows each time a death is recorded. It shows indifference, impassiveness and acceptance. Repetition of the phrase draws us towards the force of death and points us to how inevitable it is. I found the use of the phrase fascinating, it just draws us to the fact that ‘death is inevitable and happens to all of us’.” For the artist, the book provided additional inspiration as well as the title for her ongoing solo show “So It Goes” at Mumbai’s Chemould Prescott Road.

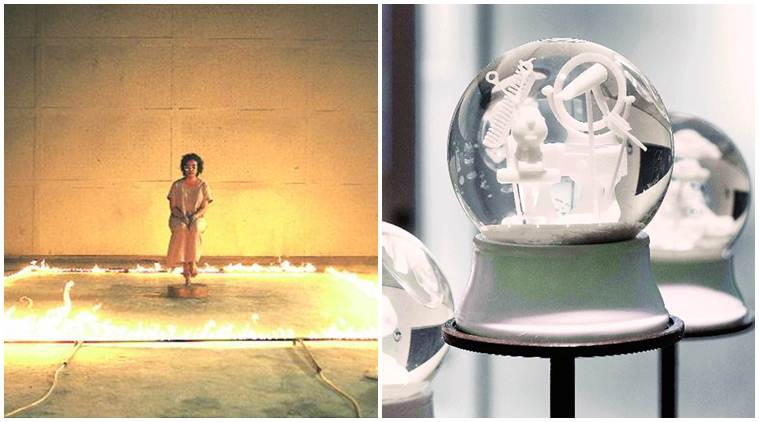

The 47-year-old, who lives and works in Mumbai, has had a long-standing preoccupation with death. Unlike Vonnegut, however, she does not deploy dark humour as a way of confronting the question of death. Her approach, even with its meditative and ritualistic aspects, is far more direct than the writer had allowed himself. For example, in The Invisible Father, wherein the artist captures 13 key scenes from her life inside snow globes, along with nail clippings that are an exact representation of the length that Kurulkar’s late father’s fingernails would have grown and been clipped into during his life. It’s a poignant reminder of a formative absence from the artist’s life, since she came face-to-face with the finality of death as a young child. “The earliest realisation as an artist has been, for me, to decipher mortality, death and life,” she says, “All my undertakings have been studies in various methodologies to overcome the fear of death. In that pursuit, I have tried to inspect what lies beneath all that is tangible and visible. The experience of death as a child and its after-effects recurred in my journal writings and then filtered quite organically into my work.”

Since life and death are yoked together, an understanding of the “tangible and the visible” — the body and all that it is made of — is also an important part of Kurulkar’s oeuvre. For many years now, the artist has created replicas of her body, or parts of it, in examination of her own mortality, such as in the 2015 work Kenosis, in which a terracotta replica of her heart was immersed in water and its slow dissolution recorded. This was, she says, a confrontation that she had staged, in an attempt to reach a stage of surrender and “acknowledge my fear to the world through my work, by making my body a transient medium”.

In the current exhibition, which emerged from Kenosis, other such confrontations are staged. For example, in Earworm, we see a series of images made after Kurulkar created a 3D replica of her skull, inverted it and filled it with water, and then charged it with deep notes of a cello rendition of Haneshamah lach, a Bene Israeli song that she had heard at funerals. Then there’s the ritualistic wrapping in fine porcelain sheets of 382 uteri in the title work So It Goes. Each piece, a replica of the artist’s own uterus, stands for a menstrual cycle experienced by the artist till date, becoming a symbol of potential life and eventual death. A starker confrontation with the body comes through in A Premature Burial, in which pieces of terracotta clay — which were once a single lump of clay equivalent to Kurulkar’s body weight — are strung together with surgical thread.

While clay and water recur as materials of choice in her work, it is Time itself that Kurulkar characterises as an important medium. The role of Time as a medium comes through best in the video Synonym, which depicts the artist perched on a revolving stool, as she is exposed to the elements of water, wind and fire — an attempt to turn the body into a metaphorical piece of clay. “Turning this piece into a video was essential to connote the dizzying passage of time and the elemental nature of our existence. The incessant barrage of primitive forces one after the other is supposed to ignite a relatable claustrophobia resulting from our realisation that ultimately we have little choice but to succumb to the mercy of something larger than us,” she says.

“So It Goes” is on view at Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, till November 22

The Invisible Father; Synonym

The Invisible Father; Synonym

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario