‘Everything he wrote was imbued with the people, the art of India’

Parvati Sharma on her new book on emperor Jahangir, digging him out of obscurity and why the Mughals continue to be labelled outsiders.

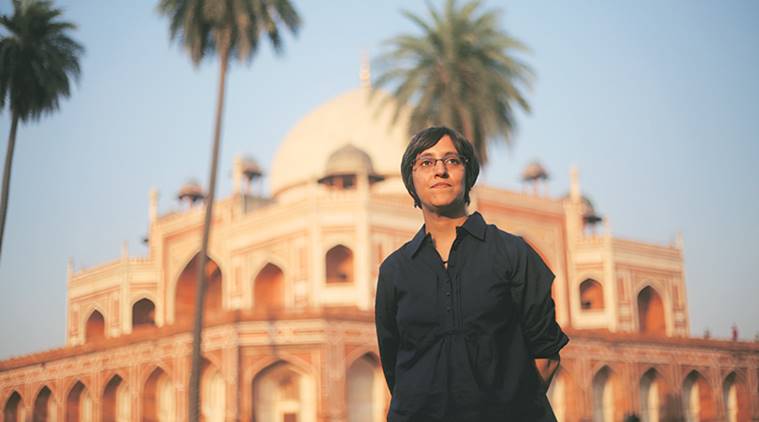

The king’s speech: Parvati Sharma at the Humayun Tomb, Delhi. (Express photo by Tashi Tobgyal)

History remembers Jahangir’s father Akbar as a large-hearted king and his son Shah Jahan as a builder of great monuments. When it comes to Jahangir, he is best remembered as the love-struck prince of Mughal-e-Azam (1960). How did you know him before you started researching him?

I had the same impression, that he was often drunk and that he liked painting but other than that there was just a vacuum. It has been fascinating to discover someone who has been completely buried under the fame of his father. Akbar overpowered him in life and in history. Then comes Shah Jahan, who went on to build the Taj Mahal, and how can you top that? Writing on Jahangir has been like digging him out of obscurity and it’s been very rewarding.

In your book, Jahangir: An Intimate Portrait of a Great Mughal (Juggernaut), you call him a man of multiple truths. Was there anything about him that surprised you?

The way most people know Jahangir is through his love for Anarkali, a grand passion, all of which is not true. What is lesser known, and in a way is a much more fascinating and richer fount, is his relationship with Nurjahan. It’s very tempting and natural to valourise young love and young passion, but in Jahangir and Nurjahan you have a middle-age love, respect and an ability to work with each other. Even in the modern world, it isn’t common to find a man of such power and his wife working so well together. To find that was a surprise. Nurjahan has been painted as this villainness but she is an equal partner and Jahangir is a person who recognises her talent and gives her responsibilities. What was also surprising was his sheer candour. He writes so freely about ordering Abu’l Fazl’s assassination, for example. Or about his drinking problem. You can’t help but be drawn to him.

Jahangir’s rule was book-ended by rebellion but was largely peaceful. He was a patron of the arts, an affable emperor who was also capable of an almost casual cruelty.

Yes, it was sometimes casual, sometimes a thought-out cruelty but how are you going to judge a 16th-17th century emperor by modern-day sensibilities? But it shows what that kind of absolute power can mean. Reading Jahangirnama, you get a sense of what that kind of impossible power and wealth could lead to. Unlike his predecessors, Jahangir was the first to enjoy the fruits of that power and wealth. One of the most evocative stories was one in which Jahangir catches a dozen-odd fish and releases them back into the waters — but with pearls pinned to their noses! There is another instance when he chops off the fingers of a gardener because he had cut a few champa trees. This is power. When you are emperor of the whole world and it’s your sense of power, almost divinity, that the world belongs to you and everything in it belongs to you and you can do anything with it. But he was also a person of great affability, people collected around him and this may be one of the reasons his rule survived over two decades. He was a man of detail who recorded everything and had a huge interest in art. In fact, two recurring phrases in Jahangirnama are, ‘I have recorded this because it is strange’ and ‘I have summoned my painters’.

Someone asked me, ‘Is Jahangir a good guy or a bad guy?’ Well, if someone is only one or the other, they cease to be interesting and Jahangir is interesting.

He was interested in many religions and there were rumours that he had almost converted to Christianity. What do you make of that?

He would have inherited this kind of eclecticism if that’s the word, and his open-mindedness about religion from Akbar. Thomas Roe, England’s first ambassador to an Indian king, says about Jahangir that he has been bred without any religion. Akbar was so eclectic, to the point of eccentricity, that his children may have inherited a sense of scepticism towards religion and an ability to question. Jahangir had both scepticism and enthusiasm for various aspects of religion. Christian iconography was exciting to him and his conversations with a Hindu ascetic, Jadrup Gosain, fulfilled something in him. At the same time, whenever he is confronted with superstition or something not verifiable, he would want to verify it. For example, when he goes to Pushkar and they say the tank there is bottomless, he has it measured.

You write about Jahangir’s visit to Kabul, a place of cool streams, melons and gardens, which he refers to as home. And then he writes the one sentence that says more than a dozen books could of how Indian the Mughals had become: ‘The excellence of the fruits of Kabul notwithstanding, not one is as delicious as the mango in my opinion.’ So, was the fourth Mughal Emperor the most Hindustani of them?

I think so, the most Hindustani until then. He had a Rajput mother, he had Rajput wives, so in his blood, too, he had become Indian. He was born in Sikri, in the heart of north India. Babur would write often about melons and Jahangir was almost mirroring it with mangoes. He writes on where he got them from, which date he got the last mango of the season, and then when he visits Kabul, he says their fruits are nice but nothing matches the taste of mangoes. At the beginning of the Jahangirnama, Jahangir says, almost for duty’s sake, that we must conquer Samarkand but he shows no intention thereafter. He moves nowhere near Samarkand, he stays here and he writes about flowers, trees, about Tansen singing. Everything he writes is imbued with the scenery, with the people, with the art of India. In him, you can sort of see the settling down of the Mughals as people who are of this land.

The Mughals settled down in India but centuries later, some are still questioning their Indianness. As someone who has written a book for children on Babur (The Story of Babur, 2015) and who has now written on Jahangir, do you find this constant othering of them disturbing?

It would be funny if it weren’t so disturbing. It’s a petty kind of action, that we have now taught them a lesson, we have changed the name of a road or of Allahabad and we are rediscovering some great ancient freedom. I don’t see what it accomplishes in the end to insist that the Mughals were foreigners, that they looted this country. If they did loot or pillage, where did they take it? They stayed right here. It’s a fact that the Mughal Empire was one of the richest empires in the world and was a huge centre of manufacturing and trade.

It would be funny if it weren’t so disturbing. It’s a petty kind of action, that we have now taught them a lesson, we have changed the name of a road or of Allahabad and we are rediscovering some great ancient freedom. I don’t see what it accomplishes in the end to insist that the Mughals were foreigners, that they looted this country. If they did loot or pillage, where did they take it? They stayed right here. It’s a fact that the Mughal Empire was one of the richest empires in the world and was a huge centre of manufacturing and trade.

If the empire was profitable, then where is the evidence that the country did not grow with the Mughals or that they didn’t grow with it?

When you think about it and it makes so little sense, you have to start thinking about it in terms of current politics. It’s sad and tragic to even say it but clearly the reasons the Mughals continue to be thought of as foreign within a certain political discourse is because they were Muslims. The antipathy is towards their Muslimness and that antipathy flows from nothing that the Mughals may or may not have done but it flows from a political discourse. It’s a discourse that’s led to a constant sense of mostly manufactured conflict and the Mughals have become unfortunate pawns or fulcrums of that.

In today’s polarised world, it’s difficult to imagine that in Jahangir’s time, people had the freedom not just to profess any faith, but to ‘even rail against another’s without undue trepidation’?

I wasn’t expecting it but you have some random Englishman going on top of a mosque and declaring, ‘No God but God and Christ the Son of God’ and not being punished. The Jesuits came, they celebrated Easter and said they couldn’t believe they could practise their religion so freely. When you have the confidence of your faith, then you don’t mind if someone says something critical about it. I think it shows a certain kind of cultural self-confidence that existed then.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario