The revolution never arrives

A stark political fable, Benyamin’s award-winning novel offers a powerful portrait of a divided State

Jasmine Days is a stark political fable — the parallels between the apathy to history of upper-middle class metropolitan India to history, and the citizens of a city that has not known democracy is often disturbing.

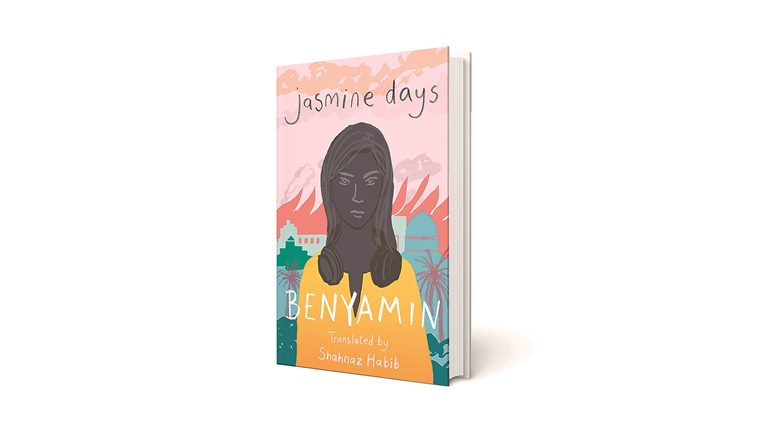

Title: Jasmine Days

Author: Benyamin (Translated from Malayalam by Shahnaz Habib)

Publisher: Juggernaut

Pages: 264

Price: Rs 499

Author: Benyamin (Translated from Malayalam by Shahnaz Habib)

Publisher: Juggernaut

Pages: 264

Price: Rs 499

We must wash our eyes with darkness to see what we want to see.” This line from Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, quoted in the epigraph to Jasmine Days, which has just bested a formidable shortlist to win the JCB Prize for Literature, might be a way to understand Malayalam writer Benyamin’s project in this novel. The journey of his protagonist, Sameera Parvin, and, by implication, his readers, takes her out of this darkness, as she is drawn into a more empathetic understanding of the people she shares the City with. It is the nature of the politics of the time, however, that this seeing anew brings only loss and devastation.

Though it remains unnamed, the events in Benyamin’s novel play out in Bahrain, which in 2011 saw massive protests by Shia residents against the Sunni monarchy. Cocooned from this brewing tumult, Sameera, a young woman from Pakistan, works as an RJ in a radio station, holding her own against the “Malayalam Mafia” with her quick wit and sharp tongue. “On my first day in the studio, I was shocked to see all the Indians walking around. How would I work among so many monsters?” Sameera learns, like many other migrants swirled together by the tides of globalisation, to keep national or tribal identities aside.

But that is not the choice of all those who work and live in the City. Sameera’s friendship with Ali Fardan, which starts with a shared love for music, scoops her out of her home-to-office-and-back route and allows her to roam the City’s cafés and streets. It will eventually force her to extend herself to perilous limits. Ali is a second-class citizen in his own country where the majority are like him — Shias disenfranchised by a Sunni elite. As revolution stirs through the city, Sameera learns to feel the pulse of its disenchantments through Ali’s experience. But what of the immigrant’s place in this upheaval?

The answer lies in Taya Ghar, the subcontinental joint family from Pakistan that is facing a few subterranean mutinies of its own. Facebook is not allowed to its women, but Sameera gets her way on most other things; her younger cousin is carrying on an affair, sexting included. The relationship between the feisty Sameera and her self-effacing father is a tender one, but Benyamin doesn’t dwell too much on it. It is the polis (and the politics) that is urgent to the novel. Both Sameera’s taya and her father are members of the monarch’s security forces, mostly foreigners, who “protect His Majesty from his own people”. As protests turn into rage against Indians and Pakistanis, and as her family defends the monarchy on the streets, the role immigrants have played for years in the citizens’ powerlessness dawns on Sameera.

As in the first of his Malayalam novels to be translated into English, Goat Days — and more so in this one — Benyamin is at pains to convince the reader of the authenticity of his story. There are multiple fictions nesting in this story to convince us — first, that the novel in our hands is not written by Benyamin, that it is not a novel at all, but a first-person account by Sameera Parvin, found and translated by the author. Second, that Sameera is not a creature of his imagination; instead, Benyamin is a conduit for her story. It is an erasure Benyamin carries out even in the language of the novel, removing all writerly hubris to let the voice of his first-person narrator come through. That voice was the power of Goat Days, as it is in this novel. Sameera’s, though, is not a voice in the desert, as Najeeb’s was, but a woman finding herself in the cacophony and conversations of workplace, home and revolution. But unlike in Goat Days, it remains a voice lacking in interiority. As the novel is overtaken by politics, Sameera remains undiscovered. The latter half of the novel, with its contrived end, the devastating, and wholly unconvincing, choice it offers Sameera, its grating argumentative-ness, takes on the nature of a chamber-room drama.

Nevertheless, Jasmine Days is a stark political fable — the parallels between the apathy to history of upper-middle class metropolitan India to history, and the citizens of a city that has not known democracy is often disturbing. The revolution never arrives, and its swift repression is streamed on YouTube. Benyamin offers a powerful portrait of a divided polis, with each section enclosed in its own darkness and echo-chambers, and weaponised against each other — even as master-manipulators of power survive, a little more entrenched. Indeed, a novel of our time.

For all the latest Lifestyle News, download Indian Express App

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario