Wolfgang Kubin: “No innovative culture without contact”

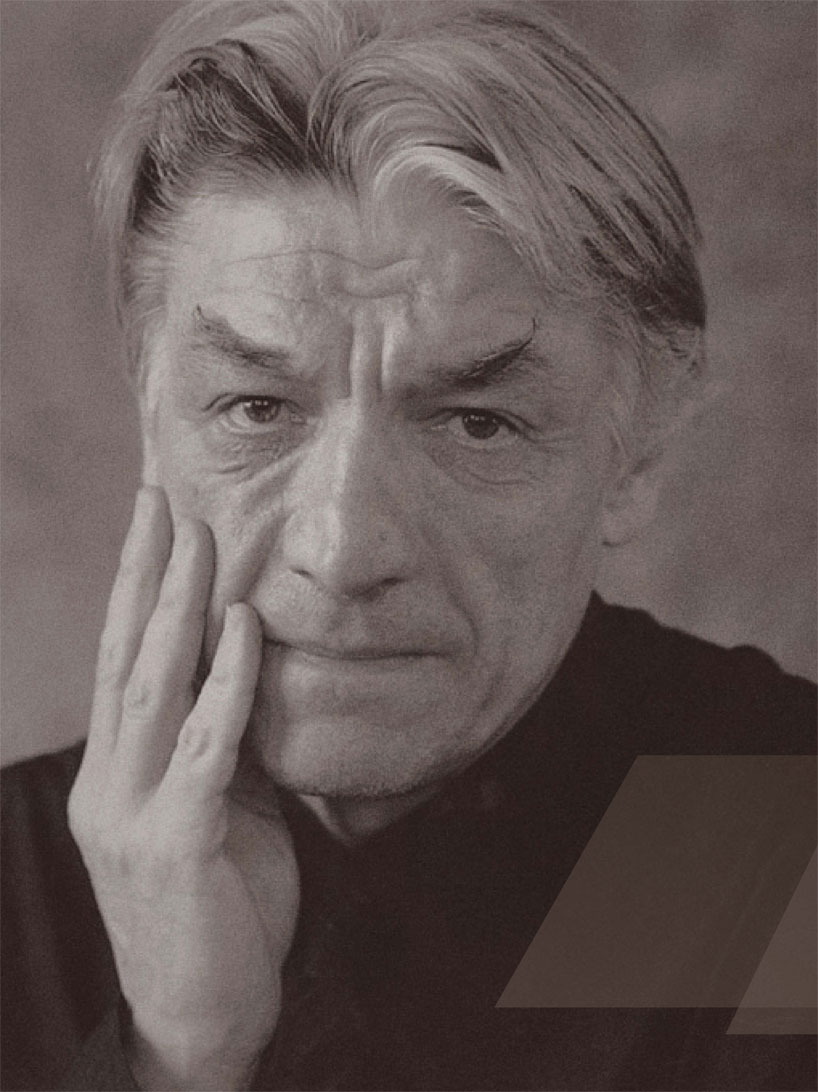

An exclusive interview with German sinologist Wolfgang Kubin, one of the best sinologists in Germany, who not only teaches Chinese language at the University of Bonn and translates Chinese literature, but also travels frequently to China.

Confucius Institute Reporters Cheng Ye & Zhang Lili 本刊记者 程也 张丽

Students, literature enthusiasts and reporters hearing the news rushed into the classroom at Beijing Nationality University. They were whispering when they saw a gray-haired professor carrying a bike helmet walk in. The lecture quickly came to the point and the audiences were getting more enjoyable as the professor quoted copiously from many sources. All of a sudden, the professor had some doubts about the falling tone of a Chinese character being mentioned. He then took out a Chinese dictionary to check and verify. The classroom became so quiet that the only sound heard was the page flipping on the rostrum.

This professor is Kubin, one of the best sinologists in Germany, who not only teaches Chinese language at the University of Bonn and translates Chinese literature, but also travels frequently to China, as he is often invited to give lectures in many colleges and universities. He has no problems to express himself in Chinese, but he always carries a Chinese pocket dictionary for verification at any moment. Students who are familiar with him have got used to his earnest manner. In addition to Chinese, the vibrant and earnest Professor Kubin can speak many other foreign languages. What is the relationship between languages and cultures in his point of view? During Professor Kubin’s visit in Beijing, the Confucius Institute took an exclusive interview with him.

Character Profile

Born in 1945 in Celle, Lower Saxony State, Germany, Wolfgang Kubin is a professor at the University of Bonn, translator, writer, member of the German Translators Association and the German Writers Association, chairman of the Writers Association of Bonn, and one of the most important sinologists in Germany. He earned his doctorate in sinology at the University of Bonn with his dissertation “On the Lyrics of Du Mu” (lun dumu de shuqing shi) in 1973 and obtained the qualification of sinology professor at the Free University of Berlin with his paper “Empty Mountain – Chinese Literati View of Nature” (kongshan: zhongguo wenren de ziran guan) in 1981. Since the 1980s, he has published more than a hundred of books, including monographs, translations and compilations in German, English and Chinese. Since the 1990s, he has achieved brilliant successes in modern Chinese literature, especially in the translation of new poetry. He is presently a specially appointed professor of Beijing Foreign Studies University and serves as dean of the German Department of the Ocean University of China.

Reporter: Professor Kubin, could you share your learning experiences and study insights with us as you can speak many languages?

Kubin: German school system requires us to learn more foreign languages, so I studied several languages at high school. After entering the university, I was used to learning languages and up till now I have been learning a variety of languages. To learn foreign languages, you should often contact with foreigners. After I studied English at high school for five years, I went to England and stayed there for four weeks. As I was in the environment with English speaking people everywhere, I was soon able to speak English fluently. Therefore, it’s necessary to have a language environment, which could be found on your own. For example, when you study abroad, you should try your best to communicate with local students and should not always stay with your classmates who only speak your mother tongue.

When I studied theology at the University of Münster, I read the English version of Send Meng Haoran to Guangling by coincidence and I was impressed by the beauty of Li Bai’s poem. Thus, it aroused my interest in Chinese poetry and inspired me to learn Chinese language. I received systematic training for Chinese language in Germany at first, and then obtained an opportunity to learn standard modern Chinese at a Beijing language school in 1974. I studied Chinese from 6 in the morning to 12 at midnight during my stay in Beijing for one year. I studied assiduously and my teachers were all superb.

Reporter: What role do you think the exchange of languages and cultures plays in international engagement?

Kubin: Language is the key to thought. Languages consist of many words and each word has a long history. Therefore, some people say that the history of a word should be excavated to get the concealed yet extremely important cultural connotation. The exchange of language and culture is actually the contact between two kinds of people, nationalities, languages and cultures. If we do not contact with others, there is no way to innovate culture. Hence, I believe that the innovation of culture is the communicational contact and the learning from each other.

Reporter: You once mentioned that Lin Yutang and Eileen Chang (or Zhang Ailing in Chinese) were excellent Chinese writers. They had something in common, as they mastered foreign languages very well and could write bilingually. However, some people believe that foreign languages will destroy the language sense of mother-tongue writing. What do you think about this?

Kubin: Lu Xun advocated that good foreign literature should be translated into Chinese to further strengthen the exchange through translation. I believe that the mother tongue and national culture can be reflected in other languages and cultures. As early as in the Goethe era, all German writers were translators. At present, German writers, regardless of their age of 40 or 70, can translate. They would pay attention to the introduction of foreign colleagues and their peers. If they did not know foreign languages, they would not have been able to introduce foreign literature and their peers. If they did not know foreign languages well, they would not have been able to read the original works and to absorb other languages to enrich their own expressions.

Reporter: Since 1989, you have worked as an editor-in-chief for the journal Orientierungen to introduce Asian culture and the Minima Sinica to introduce Chinese humanities. Thank you very much for your long-term care and recommendation regarding Chinese literature. You once mentioned that many contemporary Chinese writers had their books published very fast, which was quite different from German writers in respect of the writing speed. What do you think of this phenomenon?

Kubin: I have begun to write poetry since I was 16 or 17 years old, as I was fond of it. After I read Li Bai’s poetry for the first time, I have been always fascinated with Chinese poetry. Chinese poets had written poems 2,000 years before the emergence of the first German poet. How amazing it is to see so many outstanding works had been written in Chinese!

I have also read a number of Chinese literary works. Lu Xun’s works are basically short stories or novellas, with very peculiar language. You will find that his language is extremely terse and no Chinese characters can be deleted or added. Classic works are gradually honing out. Isn’t it like a Chinese saying, “The edge of a sword becomes keener through honing and the fragrance of plum blossom sharpens in the bitter cold”? Contemporary German philosophy advocates the loneliness and people should learn to live in loneliness. If you had not learned to live in loneliness, you might not have been able to write an excellent work. Thomas Mann, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature, said that he could only write one page a day and over 300 pages a year. Sometimes it would be less, because the page written on the previous day needed to be modified on the following day. A well-known novelist in Germany once told me that he could only write one hundred pages a year. I have often criticized some contemporary Chinese writers as they are only marketoriented. Of course, popular fiction writers always want to write more and fast. However, it’s different between the classic and the popular.

Reporter: Your harsh criticism is well-known. However, you wrote in the preamble to Chinese Literature in the 20th Century, indicating that you had all your love dedicated to the Chinese literature for 40 years.

Kubin: Yes, that’s right. I criticize because I have my own value judgments. German culture is a culture of suspicion. From our point of view, if there were no criticism, there would be no development. Criticism should be allowed in any good societies. Therefore, I think that some Chinese people, especially intellectuals and politicians, should understand the positive side of criticism. Furthermore I think it’s normal if I criticize you today and we can still be friends tomorrow. If in the future I meet the people whom I have criticized, I will take the initiative to meet them, shake hands and talk with them. If they think that I’m wrong, I will patiently listen to their points of view. Wang Anyi commented on my criticism which is “the deeper you love, the huge agony you suffer”. I think she understood my criticism. I have criticized Mo Yan a lot, but we are still friends. He would say, “Welcome your comments,” and “Let’s go to drink liquor together”.

Reporter: What is “good literature” from your point of view?

Kubin: Good literature should be for everyone. I think that an author should have an international character and represents a kind of internationalism rather than localism. Take Gu Cheng as an example. He is a good poet and his poems, written in Chinese, belong to international poetry. Each language has its own world and history, and each writer has his or her own perception. We must and should have our native silhouette and cultural background, but we should express in an international way. Otherwise, it’s impossible to communicate internationally.

Reporter: You have published Confucius, Mencius, Laocius and other books in Germany. Do you think that cultural barriers exist in Westerners who read classical Chinese literature?

Kubin: There are barriers at the early stage, but don’t worry. If something can be immediately understood, it’s not worth thinking about. German readers expect to get this kind of reading materials which can help them think more about some new issues.

Within a long period after the 1960s, European literati had the concept that Confucian ideas could not make people excited. Hegel once said that the doctrines of Confucius were just clichés. However, I have now changed my concept, so have the European sinological circles. Confucius is gradually attracting the attention in German speaking countries. Confucius is a humble man. Though we regard Confucius as “the teacher for all ages”, he insisted that he also needed a teacher. “Out of three men, there must be one who can teach me.” It’s really a great statement. I am pleased to introduce classical Chinese literature to Germany. This change is just the issue of “traditional culture and modern heritage”. For a nation or a community, the tradition is its foundation. In Germany, we believe that the past is the future and the human soul needs tradition. After World War II, we have felt that we had made too many faults and we should now embark on a new path. We want to learn from all other important cultures and nations, including China.

Our age is now an era of dialogue and cooperation. We had too many wars before and we cannot keep on doing that. I think we should learn from Chinese people how to resolve problems, as the Chinese advocate the harmony.

Reporter : Germany ’s Goethe Institute has many outstanding cases in respect of language promotion and cultural communication, which are worth learning by the Confucius Institute. What’s your opinion about “culture export”?

Kubin: “Culture export” is right. But before it is exported, you should check what others have already done and never make reduplication. For example, I have found that Chinese literati and intellectuals are not quite aware of what we have translated because of language barriers. They are working over these again. I think it’s unnecessary, because Chinese literature and philosophy have a history of several thousands of years and a great number of works haven’t been translated yet. It’s better to translate those parts.

The Goethe Institute has not only taught German language, but also hoped people to accept German culture through the promotion of German language. I think this is also the task for the promotion of Chinese language. Language and culture are inseparable. Chinese teachers I met in Germany are good at teaching Chinese language, but they are not good enough in the dissemination of Chinese culture. I have taught modern Chinese in Bonn for a decade. I have always introduced Chinese culture to my students at every lecture on modern Chinese.

As for the way of the dissemination, I think that a Chinese writer’s view is apposite when he mentioned that the exhibits displayed in the exhibition hall overseas were not for foreigners, but for the patriotic overseas Chinese. I think when you are abroad you should think from the perspective of foreigners, including their needs and expectations. For example, Germans are generally interested in philosophy, literature, arts and something challenging and difficult.

Reporter: Speaking of international communication, China hopes to face the rest of the world with a friendly smile, but it is often misunderstood. What do you think of Westerners’ perspective about the “Image of China”? Are there any changes over the years?

Kubin: We should not only observe our nation based on our nation, but also review our nation from the perspective of other nations. It’s impossible for a nation not to contact with the cultures of others, because the innovation can only be achieved by way of exchange. I have personally studied the image of China, especially in the literature of Germany and German speaking countries. But I’m afraid that what you mentioned is not necessarily the image of China in the literature but the image in the eyes of the media. Germans like to read newspapers and every city publishes its own newspaper. The most important newspapers, such as Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (Frankfurt Express) and Die Welt (The World), are objective to report the news in China and they are friendly on the whole. It’s rare to have a word that makes you feel the reporter is criticizing and repudiating China. On the other hand, I think that you should not be sad if there is a criticism, as there are various critical voices in Germany every day. You should first consider why it is said so and whether this way of saying is reasonable.

The criticism to the Confucius Institute or the critical voices are generally not from Germany, but probably from one or two persons, who brings little influence, and with whom we 99 percent of our sinologists disagree. The relationship between the Chinese and Germans is good. Our perspectives are different for sure in some respects, but our relationship is friendly. Therefore, a lot of problems could be resolved.

Published in Confucius Institute Magazine

Published in Confucius Institute MagazineMagazine 26. Volume III. May 2013.

Read in the print edition

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario