Written by Pooja Pillai |Updated: November 22, 2018 12:19:35 pm

Writing poetry is a sort of sadhana: Jayanta Mahapatra

Jayanta Mahapatra, who was Poet Laureate at the Tata Literature Live! Festival in Mumbai this year, on what it takes to write poetry, looking back at home for inspiration and how physics taught him brevity.

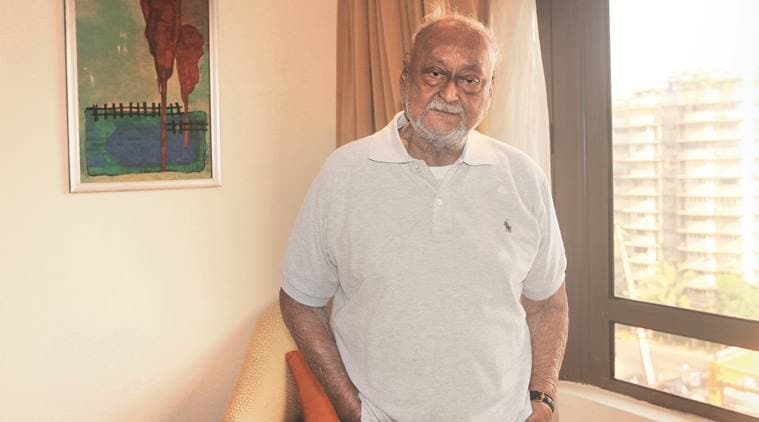

Jayanta Mahapatra in Mumbai. (Express Photo by Ganesh Shirsekar)

You’re the Poet Laureate at Tata Literature Live! Festival this year. What does that honour mean for you?

At this stage of my life, awards don’t mean very much, but then it’s a sort of recognition again for the work that you have done and poetry doesn’t work overnight. You have to struggle, work really hard. It’s a sort of sadhana that you have to go on, working on poem after poem, and you don’t know whether the poem you’ve finished is a good, strong, intense poem or not. So it’s a long drawn-out process, you know, and after 50 years to get an award – yes, it does mean something and I do feel happy.

It’s the senior poets who become Poet Laureates.

Tomorrow is just another day when I have to try to write another poem, so being a senior poet doesn’t mean much. Only that it brings more younger poets to me. More poets are drawn to me and they ask how their work stands against today’s contemporary poetry and that’s something to be happy about. Discussing (poetry) with younger people (is good) because the younger blood infuses you with that energy to proceed.

Do younger poets seek you out for advice?

I live in a small town, but there are poets who come and even if they don’t talk about poetry, they come and sit down and we have snacks and chai and we go to the interiors of the state to look at village life. Odisha has a lot of Adivasis, and in some parts, the poverty is still very alarming and that’s what irks most of us, that even after 70 years of independence, we haven’t much improved the standard of living in the remote countryside. Although in the cities and towns, people are quite well-off, and they do have two meals a day.

How bad is the poverty you see?

I’ll tell you a story from three years back. We have a big forest range called Simlipal in the north of Odisha and there in the remote hills, I had gone with a few friends on a sort of tour. I strayed from my group and went into the jungle. And there was a stream passing by, and a woman was bathing there with a little three-year-old son. The woman was an adivasi and I looked at her, her face was wrinkled. Her arms were like my own and she was looking very old, as though she is 60-65 years old. But then the little child with her was only three years old and when I looked at her carefully and knew she would only be 20-21 and that’s what pained me very much. So I asked her, mausi what are you going to have with your rice today and the answer she gave shocked me. She said babu, where will I get rice? Only when some people from the cities (come) or during election time they come and visit us, they give us some money or bring us rice, then only we have rice to eat otherwise, we just go into the jungle and get berries and roots.

Sp hearing these things really hurt one. Sometimes during election time people do get in and help them, but nothing much has changed. That’s what I write about, the things that I have seen. My poetry comes out of my life, and poetry is an expression of life. And poetry doesn’t only remain in the dining room of a hotel or in the President’s garden in New Delhi. It’s also in the slums of Cuttack or Mumbai.

Is it your duty as a poet to write about all this?

I see it as somebody who can’t just sit back. You can’t just be in the audience and watch a play. You should get in. Of course, you can’t do the work that Mother Teresa does. So you in a way a poet is a coward – because he can’t move out into the field and can he pick up leper from street and take to hospital? Noi, he can’t. I can’t, so I’m a coward n? So what can I do? I sit down in my room and write a sad poem at my desk, and you think that’s a great thing to deserve an award.

Do you believe poetry changes anything?

Well, all these years poetry has never done anything to change society, but a person writes in the hope that something might change someday and probably these things take time. I wouldn’t know. Then again, the disparity between rich and poor in India has been increasing at an alarming rate these couple of years and that’s again a thing for grave concern.

Has that become especially bad in the last few years?

Yes, I do.

You were among those who returned your awards in 2015 to protest what you saw as intolerance.

I don’t know whether I was right or wrong, but I wanted to do something. I’ll tell you why I returned the award – you know when you don’t agree with your parents, your father or mother says something harsh which is totally untrue or unjust, so what do you do? You sometimes rebel, you have to show your sign of protest. You shout or run out of the home and that’s what I did. I didn’t like what was happening, so I returned the government award, the Padma Shri. I didn’t return the Sahitya Akademi award, only the Padma Shri. And I would do it again.

As someone who grew up in Christian household, do you feel there’s a greater intolerance against minorities today?

I think there is some sort of increasing hostility that is there in the air, of course. It’s not very evident. My grandfather became a Christian. We had terrible famine in 1866 and he didn’t have anything to eat so he walked the 30 or 40 miles from his village, to a Christian missionary camp and they took him in and after that he was of course rejected by Hindus, his family didn’t take him back, so naturally he was converted. So I have heard murmurings about myself, people saying that Jayanta Mahapatra is a convert and that hurt a little. My grandfather didn’t have enough to eat, so what does religion matter. I don’t want to say anything against anyone. But there is a strong over confidence and a sort of overpowering feeling that you are a Hindu.

A few years back, during Christmas time, a number of churches were attacked. There was a Swami called Swami Laxmananda was killed and till today, they haven’t found out who killed him. And it’s a strong Naxalite base, where this happened. So repercussions happened and they burnt all the churches, killed people and a number of people were driven away. This has been happening. But Cuttack, where I live, is fine. We live in perfect harmony – Hindus, Muslims, Christians, everyone.

Your relationship with Cuttack turns up frequently in your work.

I write about my hometown. I was born there and I grew up there. I don’t like certain things which are happening now. I don’t like intolerance of the youth. And then everyone wants to hurry up. I go stand in a queue at the post office and I see the impatience on the faces of young people who are standing behind me. Any little loophole, they would find it and exploit it. It’s all going somewhere but I never understand going where!

But you don’t want to leave Cuttack also.

When I was a kid, when I was a three-month-old or six-month-old I must have eaten the mud (of Cuttack). It’s a good place. It’s an intimate place. It’s not like New Delhi for example. Any girl can go out any time and nothing will happen. Even if something happens, she needs to cry out for help or something and there will be all the shopkeepers who will rush and protect. We never come across any such cases of indecent behaviour.

You also draw a lot of creative sustenance not just from Cuttack but from the larger history of Odisha and the folklore.

The history of Odisha is like my two arms. You cut them off and then I can’t write my poetry. And all the poems I have done are very local poems. But I have tried to go beyond the local.

You still write in Odia as well as English?

Both. My collected poems came out in English. My collected poems in Odia came out called Kavita Samagraha. It’s not as big because I started writing in Odia later. I was taught in a British missionary school and we weren’t even allowed to talk in any language except English in school. Only for the time that I spent at home.

Was there a specific reason you decided to start writing in Odia?

I had already published a lot even abroad. My books had come out in the USA. I got this Sahitya Akademi Award way back in 1980s. Still, people who lived near my house didn’t know that I was a poet. If I had published, say, 10 poems in Odia in a magazine, then everyone would know me. There was this paanwala, a bicycle mechanic and then I thought let me try to write some poems for these people. People who will understand what I am saying. One poem led to another.

As a creative person, is it easy to balance the demands of both language?

I don’t know what you mean by demands. Certain things come out automatically and straight away in Odia. For the English poem, you have a phrase or a sentence and something is there. That’s on the back of your mind. You put the sentence down, that’s what I do. Then I try to work on the poem. But in the case of Odia, it’s more spontaneous. So the demands are different.

Can you tell me a little bit about the process of working on a poem?

Each poem has a different history. It has a different mode of approach and the conclusion comes in very different ways. For example, a poem I wrote about my grandfather, that took a long time to write. I was thinking about it for almost two years. But then I wrote it in a stretch. But there are many poems, that I go on writing the first draft. Then I cut it again. Second draft, third draft and fourth draft and so on. Still the poem doesn’t work out. It’s very difficult to say. It’s not a uniform process. But you know, a poem is something that you don’t know what happens in the unconscious. You put it in the first line and then, think of this as a closed box. A dark room with no light. And you enter the door and come in. That’s the first sentence. When you step in, it’s all dark. So you are exploring now. You are going to the second line, you don’t know. The mind is such a computer, it straight away goes 60 years back to something that happened in your childhood. It puts it there. And you come till the end of the dark box, if the poem has reached its perfect conclusion, then the door opens and you conclude the poem. If you can’t find the door, then the poem doesn’t work.

And what is the predominant feeling when you reach the end of the door?

It’s a thing to be jubilant about. It’s a thing to jump and leap about in the air. When you have got the perfect conclusion, you do. Otherwise, you are in a mood, in a state of dejection. You know that you haven’t done anything. Your poem isn’t a poem at all.

You have been very prolific.

Because I didn’t do anything else. You neglect your family. And I can’t forgive myself for that. It only helps your ego and now I think I have done that.

Did your family ever say this, that you are ignoring them?

Never. She never said anything, my wife, Runu.

You were teaching physics before you got published. Did that feed your practice of poetry?

Physics did help me. When I started, I started writing late. When I thought I am almost finished with my life. People bask in their glory and they are already poets and I was just a beginner poet. I sent a poem to Nissim Ezekiel, he returned it, Adil Jussawalla gave me a bad review. But then I thought I should write because I didn’t know what else to do. I was doing research in theoretical physics and I gave it up. But physics taught me a certain discipline. In the processing of words, so it taught me to use language in a very brief way. From my childhood, I was a voracious reader. When I began writing in English, I had attained a certain perfection. I used to play about with words. The language attracted me and fascinated me. When my first book appeared, it was the language that took precedence over the feeling of the poem. Because the poems are good, rich in language but zero in feelings perhaps. But physics taught me that brevity which a good poem needs. So my language helped. And physics helped for me to write a good poem.

But you say that they were rich in language and short on feelings. Was this an aspect that you actively worked on?

Yes, I didn’t say oh no. I didn’t say that. I said no, I must be failing in my endeavour. So I began.

How did you do that?

I began to read a lot of contemporary poetry. I spent my hours in the college library where I worked. I neglected my physics. My language was already good, stable. I could ape some good poets and then began writing. It took some years to develop my own style. Without reading, I don’t think you can write.

You already had the language. But then getting the feeling into the poem. Doesn’t this come more from the inside?

Yes, it comes from the inside and the surreality of the images. My poetry is full of images so I use the images. That takes a lot of work. That doesn’t come from anywhere. I must have copied from here or there, everyone does. But then I think mostly it comes from inside, from the subconscious and I couldn’t tell you how it all happens.

Did you start writing at the age of 40 or were you writing before that?

I was writing when I was 20. I wrote a couple of stories. Sent them to the Illustrated Weekly of India here in Bombay but they all came back with rejection slips which I still treasure. Then I thought I could have never write fiction. Then I was already married by the time I was 22. Gave up writing for a long time. Took up photography and that’s where the images come from. I’m a good photographer.

Advertising

Do you ever wish you’d not given up writing around the age of 22?

No, whatever has happened has happened. I haven’t thought about that. Maybe fiction would have brought me more money. I could have been a fiction writer because my prose isn’t bad. I didn’t do that and I don’t know. I gave up writing for a long while. Again ran back to physics for research.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario