Why my grandfather refused to become a citizen of India

In 1947, a line ran through Sylhet, Assam, dividing families and creating new citizens. The burden of that history is still with us.

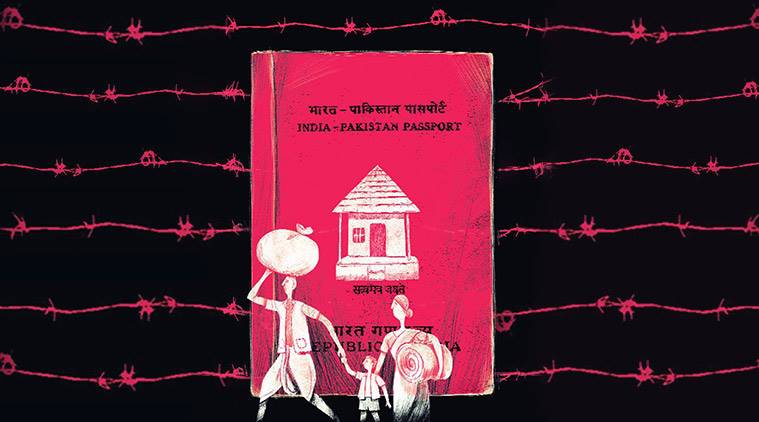

Partition had drawn a line through homesteads and belongings. (Illustration: Suvajit Dey)

The passport is red, not the familiar inky-blue. Inside, on a yellowing page, the photograph of a boy, fresh-faced and unrecognisable: my father. On its cover, below the insignia of the Ashoka Chakra is written: “India-Pakistan passport (east zone)”. That hyphen is unusual. It is not quite barbed wire between antagonist countries, being on a document meant to help hop borders. I imagine it as a narrowing path, one my father and his brothers took often in the years following 1947, from an old country to new, from India to East Pakistan — and back. Till they could do no more.

As in the north, so in the east. Partition had drawn a line through homesteads and belongings. My grandfather remained on the other side in Mongolpur village, Sylhet, adamantly rooted to the land of his birth. The sons, some of whom had travelled a few hundred kilometres to find work in the tea estates built by the British, suddenly found themselves in another country, with different destinies. Even after Partition, it was possible to travel through those checkposts with some paperwork. In the early 1950s, the first of these passports began to be issued — congealing an older, fluid cartography, turning desh and tribal homelands into nations, or even antagonistic provinces.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario