The Walls Tell Stories

Author-historian Rana Safvi takes a walk around the desolate Tughalaqabad Fort and recounts tales of its famous curse and abandonment.

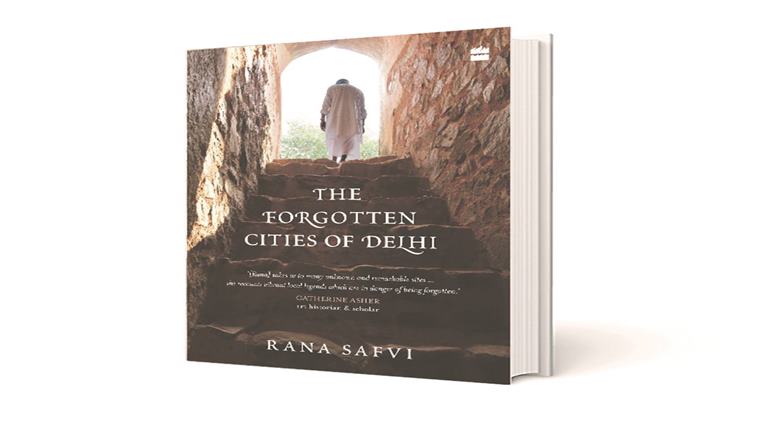

Rana Safvi’s Fogotten Cities of Delhi. (Express)

When we ask author-historian Rana Safvi to meet us at the Tuqhlaqabad Fort on a weekday morning, she immediately agrees. It is a site that she has visited innumerable times, yet she discovers more during each visit. The structure may now be desolate and ravaged but that does not take away from its grandeur, as one admires its remnants when driving down the Mehrauli-Badarpur road towards Faridabad.

Safvi arrives sharp on time, to be received by a guard who warns us not to venture into the jungle. A group of boys from a nearby village are changing their outfits for a photo shoot, and in another corner we find a couple trying to find some lone time. Safvi tells us this is the first time she has spotted a couple here. A goat grazing near a broken wall leads her to pull out her camera, as she breaks into a lore. It is believed that Sultan Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq Shah was building the fort and Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya was constructing a baoli nearby around the same time. Tughlaq decreed all labourers to only work on the fort or face dire consequences, but those who were devotees spent their nights at the saint’s baoli. As the legend goes, when the ruler forbade the sale of oil, the saint’s disciple Hazrat Roshan Chirag-e-Dilli performed a miracle where water filled in the lamps turned into oil. That is when the saint cursed the fort, ‘A rahe ujar, yaa base gujjar’ (May it remain desolate and unoccupied, or inhabited only by herdsmen). The desolation reminds Safvi of the curse.

It is stories such as these that comprise her latest release, The Forgotten Cities of Delhi (Rs 799, Harper Collins). Tughlaqabad Fort is just one of the 166 monuments that she talks about in the book. All of them are part of the five cities that made Delhi — Siri, Tughlaqabad, Mubarakpur Kotla, Jahapahan, Firozabad and Dinpahah. “Each of the dynasties either built a new capital city or expanded the old one, which has given Delhi a living history of over 1,500 years. Today, modern-day buildings and unorganised settlements have engulfed various remains of the past. Initially, I wanted to write a book on the seven cities of Delhi, but when I went to Mehrauli, I realised there is so much to write that it could make for a book,” says Safvi, 61.

The publication is second in the trilogy where she writes about historical trails in the Capital. The first, Where Stones Speak: Historical Trails in Mehrauli, the First City of Delhi (Harper Coliins, 2015), documented stories of over 50 monuments in the area. In her next, she will cover areas

in Shahjahanabad.

in Shahjahanabad.

A postgraduate in history from Aligarh Muslim University, Safvi spent her childhood in Agra. After spending three decades in Pune and the Gulf, her interest in Delhi’s history led her to make it her home in 2014. She has also authored the book Tales from the Quran and Hadith and translated Sir Syed Ahmed Khan’s Asar us Sanadid and Zahir Dehelvi’s Dastan-e-Ghadar. On her blog, she writes on Indian culture, food, heritage and age-old traditions.

Talking about Tughlaqabad, for instance, she tells us that a Turkish general named Ghazi Malik was once accompanying Sultan Qutb-ud Din Mubarak Shah, Alauddin Khilji’s son, to the area and its natural defense position impressed him. He suggested it would be an ideal location to build a fort. But Shah rebuked him. He said Malik could make one if he ever became King. Years later, in 1320, after the Khilji dynasty ceased to exist, the Tughlaqs became rulers. Malik came to known as Sultan Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq Shah and built his fortified city of Tughlaqabad.

That Safvi knows every corner of the fort is evident, as she points towards the tomb of Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq at Adilabad Fort, that stands across the road. Once upon a time, a reservoir used to surround the forts and there was a common causeway. Today, entry to both the forts is through its remains. Walking towards the Sher Mandal baoli, on one of the stones Safvi shows us a time stamp, dated June 1944 — probably to mark the renovation of the fort.

“The monuments suffered the most twice — during the mutiny of 1857, when the British destroyed many symbols associated with Independence, and during the Partition in 1947, when refugees lived there,” she says. It was a part of the estate of Raja Nahar of Ballabhgarh, and was confiscated by the British during the mutiny, as the king supported Bahadur Shah Zafar. Centuries before, the Tughlaqs had abandoned the fort, in 1327, due to water scarcity. We too, turn back from the dried baoli. Safvi tells us there is isn’t much ahead.

For all the latest Lifestyle News, download Indian Express App

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario