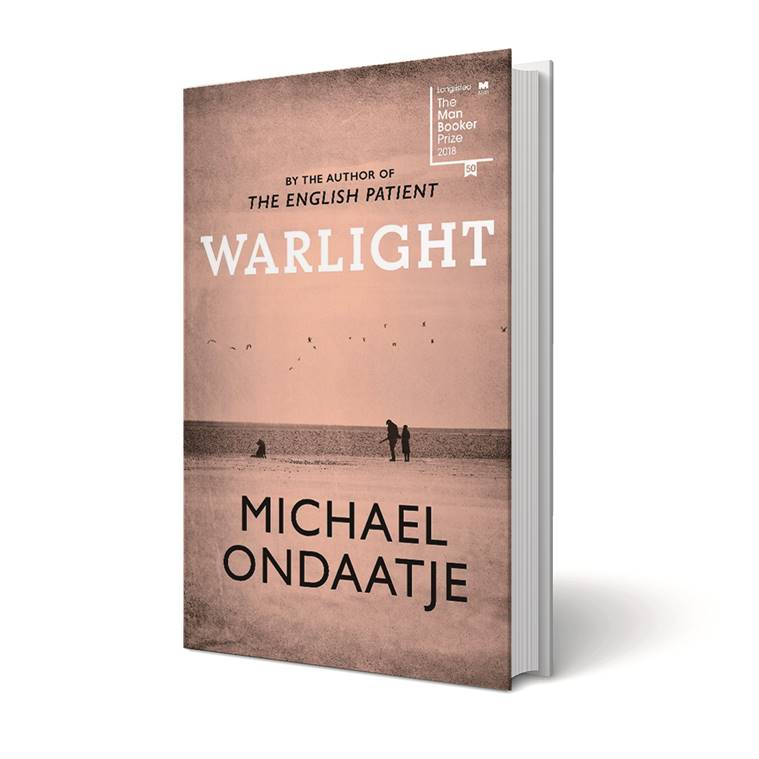

Book review of Warlight: The Kindness of Strangers

A vivid exploration of lives in the postwar decades that reaffirms how political violence never really gets a neat closure.. Ondaatje calls it warlight, and he strikes the flame by rubbing the strands of destiny together, illuminating a world deeply connected by a history of political violence.

Bomb damage in London during World War II (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Michael Ondaatje’s seventh novel is being hailed as a work of his late period, as if it were a surprisingly mellow vintage. But it’s not like his best-known work. Warlight begins with a stab at a popular spy yarn — James Bond meets George Smiley, and they sort of get along. But then the account develops into the Ondaatje that the reader has grown to expect, flashing like distant lightning in a big sky over a strangely familiar landscape. “There are times these years later, as I write all this down, when I feel as if I do so by candlelight,” writes Nathaniel Williams, the narrator of this tale set in the turbulent postwar decades, when the colonial era ended, the Cold set in, and the world changed fundamentally. “As if I cannot see what is taking place in the dark beyond the movement of this pencil. These feel like moments without context.”

Nathaniel, bereft of home and family, embarks on a hero’s journey in search of context. The beginning is slightly unsatisfactory, because the reader expects much more from Ondaatje. The setting of London trying to recover from the ravages of the Blitz reminds one of Pat Barker. The boy Nathaniel and his sister are left to the kindness of strangers as their mother returns to a career in intelligence, taking care of the unfinished dirty business of the war. The device of a woman spy is fairly commonplace, in a saturated market in search of novelty. And, while the spycraft happens in East Europe, Indian readers may get the creepy feeling that something on those lines may have been going on in our own neighbourhood, as postwar England prepared to surrender its holdings in Asia. There is, in fact, an allusion to the “burning officers” of Delhi, who incinerated incriminating

documents day and night in the Red Fort in 1947.

documents day and night in the Red Fort in 1947.

But the latter half of the novel is vintage Ondaatje — the intense evocation of the extraordinary in everyday life, as in Coming Through Slaughter, and depictions of extraordinary lives as in The English Patient. Ondaatje calls it warlight, and he strikes the flame by rubbing the strands of destiny together, illuminating a world deeply connected by a history of political violence.

Numerous examples of the circle of fate, of connections that are not obvious until they are made explicit, hold the novel together, and here’s a slightly obscure example of connectedness which may escape the general reader. Nathaniel’s father leaves the story very early, never to return, in an Avro Tudor I bound for Singapore. The plane is a descendant of the World War II Lancaster heavy bomber, which the Royal Air Force’s 617 squadron used against the Möhne, Eder and Sorpe dams in the Ruhr, which powered Nazi Germany’s armaments factories.

The Lancasters of 617 carried tailor-made bombs developed at Waltham Abbey, near a landing place on the Thames frequented in Warlight by a barge sailed by the Pimplico Darter, a former boxer and current grey market criminal, one of the shadowy strangers watching over Nathaniel. The boy presents him as his absent father to his girlfriend Agnes, and he takes takes them on as his crew, smuggling greyhounds from the Continent for the races. In a significant scene, Agnes dives into a pool in the river near Waltham Abbey, the very pool used to test the bombs that the Lancasters would drop on the Ruhr river. Much later, she works as a detonator assembler at the munitions factory at Waltham Abbey, and it turns out that during the war, the Darter had worked for the government, using his smuggler’s skills to run nitroglycerine produced at Waltham Abbey across London at night. Missing parents, present love, some greyhounds, and the hardware of a world war, tie the three characters together.

Nathaniel is the only conservative actor here. An abandoned child in a ruined city, he works his way up from hotel dishwasher to foreign office analyst. His mother watches over him and his sister by proxy, through appointed strangers, but nothing is as it seems to be. A man whom the children nickname the Moth for his “shy movements”, who is in loco parentis, turns out to be their mother’s wartime colleague. His mother is untrusting and untrustworthy, and reminds him that even Roman emperors could not tell their children the whole truth, for their first allegiance was to the state. Agnes is named for Agnes Street, where she and Nathaniel first made love in an empty house. Her real name is unimportant. He does not know the Darter’s name until the very end of the book, when he tracks him down in the Admiralty files. He discovers from his mother that the Darter’s girlfriend, an ethnographer who enthrals him with her knowledge of nature, was one of the weather-watchers on gliders over the English Channel on the eve of the Normandy landings, to figure out if the weather would favour an assault (D-Day was thus delayed by 24 hours).

All these people move on. The ethnographer becomes a TV personality, the Darter makes an unexpected marital choice, some of the strangers protecting Nathaniel and his sister are sent to the better place by people whose lives were destroyed by British intelligence operatives. Only Nathaniel remains where he was, in the world created by the mother who abandoned him. He investigates her sins, like an archaeologist, in the archives of the war: “Sometimes a floor gives way and a tunnel below leads to an old destination.” It remains an uncertain world until the very end, when she returns to Nathaniel’s life with a prophecy of her death: “When he comes, he will be like an Englishman.” But when he comes for her, in search of revenge, he is not a man at all.

Apart from a tentative beginning, which nevertheless shows what Sacred Games could have been in other hands, Warlight is vintage Ondaatje. It is a wilderness of mirrors in a deceptive light, like the contemporary world. And it tells us that political violence is never completely resolved. Its legacy is for ever, turning the future into a never-ending revenge tragedy.

Warlight; Michael Ondaatje; Jonathan Cape; 304 pages;

Warlight; Michael Ondaatje; Jonathan Cape; 304 pages;

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario