Book review of The Idol Thief: Spirited Away

This story, to me, poignantly signifies what British Company rule stood for in relation to India’s heritage and how museum collections in England were built up – through colonial loot and archaeological rapine and, as in this case, through plain and simple robbery.

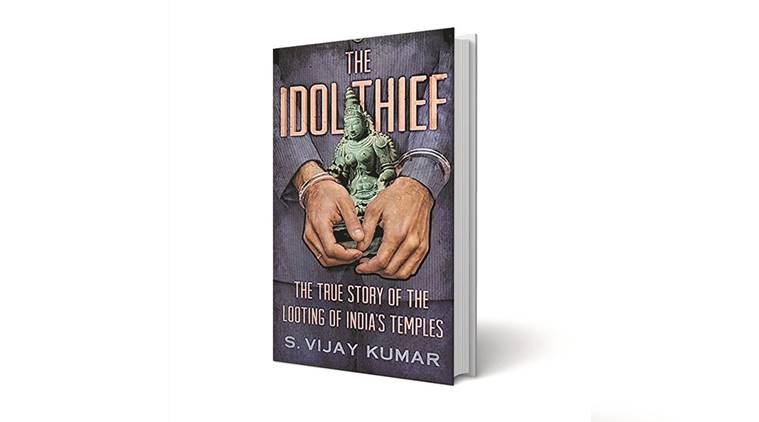

The Idol Thief: The True Story of the Looting of India’s Temples; S Vijay Kumar; Juggernaut; 248 pages; Rs 499

Some 200 years ago, a Brahman asked this of a British Baptist missionary: ‘How is it that your countrymen steal our Gods?’ As the story goes, in 1817, the Brahman’s Lakhmi image had been coveted by a British antiquarian who had many times offered him money for it. Because he had refused to sell, the idol thief ‘got his people together, and took away the goddess by night.’ The tree under which she stood remained, as the Brahman lamented, but his revered deity was gone.

This story, to me, poignantly signifies what British Company rule stood for in relation to India’s heritage and how museum collections in England were built up – through colonial loot and archaeological rapine and, as in this case, through plain and simple robbery. The gods of worshippers, though, have continued to disappear in large numbers, and for a long time now, there is a whole network of Indians responsible for the loss. I have often wondered about these contemporary idol thieves, their motivations and profits, the institutional loopholes that facilitate their activities as also the art collectors and museums that buy their stolen goods.

It is this murky world of powerful criminals where millions are made in stealing, smuggling and selling antiquities that is captured in Vijay Kumar’s The Idol Thief. It explores the theft of splendorous Chola bronzes from Tamil Nadu. At the same time, there is a great deal here about how big stone idols from Kashmir to Orissa and small terracottas from Chandraketugarh in Bengal have been spirited away.

What is it that makes this a singular book? In India, this is the first authored book that we have on the smuggling of antiquities. The government for decades has showcased spectacular festivals around artworks and icons but has not created any awareness of the magnitude of our disappearing heritage. India’s neighbour Nepal had, in 1988, published details about its losses, under the title, Stolen Images of Nepal. Authored by the late Lain Singh Bangdel, the purpose was to “attract the attention of the Western art world… many of the stolen sculptures may some day appear in the art market, or museums, but once it is proved they are stolen art objects no one has the right to possess them.” Now, for the first time, a Singapore-based finance and shipping expert has published a worthy work on how India’s treasures go missing, one that can take its place alongside Bangdel’s volume.

What also makes it distinctive is that Kumar has not written it as an academic would. He neither uses jargon nor does he tell an archive-based story about the looting of India’s temples. Instead, he chooses to tell us this shocking tale as it is, a real-life crime thriller. Much of the action pertains to some five years or so — from 2006 till 2011 — when Subhash Kapoor, the kingpin in the smuggling operations of idols, was arrested. Kumar has been able to put together a gripping tale of intrigue, because he himself has been an active participant in helping crack a number of cases.

What also makes it distinctive is that Kumar has not written it as an academic would. He neither uses jargon nor does he tell an archive-based story about the looting of India’s temples. Instead, he chooses to tell us this shocking tale as it is, a real-life crime thriller. Much of the action pertains to some five years or so — from 2006 till 2011 — when Subhash Kapoor, the kingpin in the smuggling operations of idols, was arrested. Kumar has been able to put together a gripping tale of intrigue, because he himself has been an active participant in helping crack a number of cases.

The story inevitably started, in each case, with temple thefts in Tamil Nadu. The modus operandi sometimes simply involved temple-raiders breaking open locks, removing idols, and gluing back the levers to make it seem that nothing was amiss. This ensured that it took time to realise that thefts had taken place. Local thugs by then had got these sent to Chennai-based criminals masquerading as art dealers who, in turn, shipped them to Subhash Kapoor’s Nimbus Import Export, Inc. in New York. Through Kapoor and his contacts, stolen idols from South India reached respected museums in many continents.

How some of these were then tracked down and brought back to India is equally riveting. The story has good cops and bad cops, there is sweet revenge wreaked by a woman whose relationship with Kapoor had ended, and there are outstanding networks run by individuals like Kumar and others who have helped track down these images. But what looms large is the scandalous and deliberate lack of due diligence by respected museums, including the National Gallery of Australia, the Asian Civilization Museum (Singapore), the Toledo Museum of Art (Ohio) and the Brooklyn Museum (New York). Even after photographs surfaced, taken by the robbers of the Sripuranthan Nataraja in India before it was smuggled away, the National Gallery of Australia refused to acknowledge that they knew that they had bought a stolen image. What tilted the balance that eventually saw the image being handed over by Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbot to his Indian counterpart is well told in the book.

And then, there is the pathetic state of affairs in India that Kumar documents — an understaffed Idol Wing with no archive of temple idols, the lack of initiative on the part of Indian authorities to stop shipments of antiquities, and the ease with which precious images became part of cargo that reached foreign shores. Actually, it is institutions outside the government, like L’Institut Français de Pondichéry (IFP), that shine. The IFP has been documenting temple sites in Tamil Nadu since 1955, creating a record of idols while they were still in the temples. This documentation was crucial in proving that many of the idols in museum collections abroad were stolen. Equally, devoted individuals who have faultlessly followed their call of duty — the police officer Selvaraj in India and another one called ‘Indy’ (to protect his identity) in the US, investigative journalists like Jason Felch and Michaela Boland — are the heroes of this story.

The challenge, after reading this book, is to see how the Indian government, which is so self-congratulatory about its soft power, will use its position as a global player to better safeguard its heritage. Its visible presence should not merely be confined to the optics of presiding over events around stolen images brought back to India.

Nayanjot Lahiri is Professor of History at Ashoka University

.png)

Much of the action pertains to some five years or so — from 2006 till 2011 — when Subhash Kapoor (above), the kingpin in the smuggling operations of idols, was arrested

Much of the action pertains to some five years or so — from 2006 till 2011 — when Subhash Kapoor (above), the kingpin in the smuggling operations of idols, was arrested The 1,000-year-old Nataraja idol returned by Australia to India in the recent past;

The 1,000-year-old Nataraja idol returned by Australia to India in the recent past;

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario