On The Shelf: Dies irae and Caste in Stone

Perhaps the most engaging chapter, and the most politically and analytically significant in the times we live in, is the one on “Hateful Polarisation”. In it, Devadas points to the gradual and deepening dialogue of extremes, of the diminishing room for understanding and nuance.

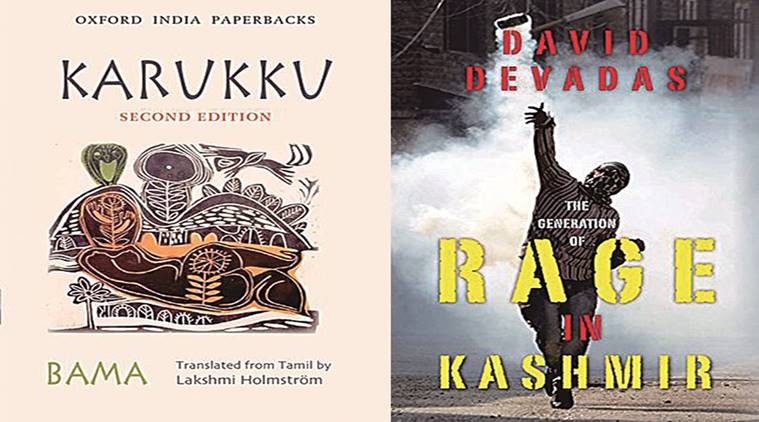

Karukku (Tamil) and The Generation of Rage in Kashmir

The Generation of Rage in Kashmir

David Devadas

Oxford University Press

Rs 495

Oxford University Press

Rs 495

To paraphrase Gandalf the Grey, all those who live in turbulent times wish that they did not. Kashmir, perhaps more than any other part of India, and very much like the bigotries that have come to define India’s national discourse, represents the moral frontier of the Indian state, and its current “turbulence” (that normalised adjective that says nothing at all). David Devadas’ The Generation of Rage in Kashmir does not, in essence, equivocate. It does not tell the story of the soldier with equal empathy and has little time for the compulsions of the Indian state. What it does do is chronicle the last decade of a dangerous politicisation of the Valley’s young people, and does so with empathy. For example, Devadas explores popular anger and upsurge at three crucial junctures since 2007, but does not fall into the trap of talking vacuously of merely “engaging with the youth”.

Generation of Rage is not an insider’s tale, and should not be read as such. Its empathy appears to emanate from a close observer of the region who has attempted to chronicle and analyse the circumstances that led up to the rise, fall and subsequent fallout of the advent of Burhan Wani and others like him. He underscores the importance of factors like widespread internet and social media in shaping the current crop of “homegrown”, millennial militants and the political blunders by successive governments in New Delhi, which have repeatedly failed to grasp opportunities for peace that relative calm offered in the past. The result? Arguably the worst bout of militancy since the 1990s.

Perhaps the most engaging chapter, and the most politically and analytically significant in the times we live in, is the one on “Hateful Polarisation”. In it, Devadas points to the gradual and deepening dialogue of extremes, of the diminishing room for understanding and nuance. The insurgents in Kashmir, argues Devadas, are neither to be dismissed as “troublemakers”, nor unthinkingly glorified as “heroes”. Devadas also locates the current conversations on Kashmir — in a larger framework — both within the state as well as in the larger geopolitics of South Asia, particularly its historical and continuing salience in India-Pakistan relations.

In the everyday headlines of violence, disenchantment, and even the odd feel-good story from the Valley, it is easy to lose sight of the context of the conflict — the continuing injustices and state of political abnormality The Generation of Rage, at the very least, helps us remember.

Karukku

Bama; Translated by Lakshmi Holmstrom (First edition Macmillan; Second edition OUP)

170 pages

Rs 295

170 pages

Rs 295

The first autobiography by a Dalit in Tamil, Karukku — which literally translates to palmyra leaves with its jagged edges — is a searing indictment of a society that has refused to move beyond caste, and how the Dalits, trampled upon for centuries, must unite and demand their rights.

The 140-page narrative delves into how caste operates within religion and how even the Christian faith is not immune to caste prejudices. A Roman Catholic by birth, Bama describes growing up in a village where everyone toils from dawn to dusk in exchange for a pittance and how they have resigned themselves to such a life. One particular instance of how her own grandmother was treated by her upper-caste employer stands out: Her paati would sometimes be given food, albeit leftovers, which the lady of the house would pour from a height into her bowl, ensuring neither touched. When asked why she didn’t object to such treatment, her grandmother asked how they could change a system that has been in place for generations.

So the author puts her heart into studying as education, in the words of her brother, will help them strip away all the indignities. After toiling day and night, she gets a job as a teacher at a school. She then decides to become a nun to try and help more children like her lead better lives. What she finds, however, is a deep disconnect between the teachings of Christ and what was practiced in reality. Dalits, for the church as well, were mere tools of cheap labour, “creatures” beyond redemption. Disillusioned, she leaves the order and struggles to rebuild the life she had left behind.

Alongside her own experiences in a caste-riddled world, Bama exhorts her people to “open their eyes and look about,” and “to stop accepting the injustice of their enslavement as mere fate”. The book assumes even more relevance today, considering the numerous crimes, including honour killings, committed to uphold “caste purity’.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario