The Progress of Love

Sita’s dharma today is to follow her own path — her swadharma. In doing so, she doesn’t reject Ram. She includes him. She transforms him. Sita is where all binaries meet. There can be no Ram Rajya without Sita’s wisdom.

Written by Arundhathi Subramaniam | New Delhi | Updated: November 4, 2018 6:00:18 am

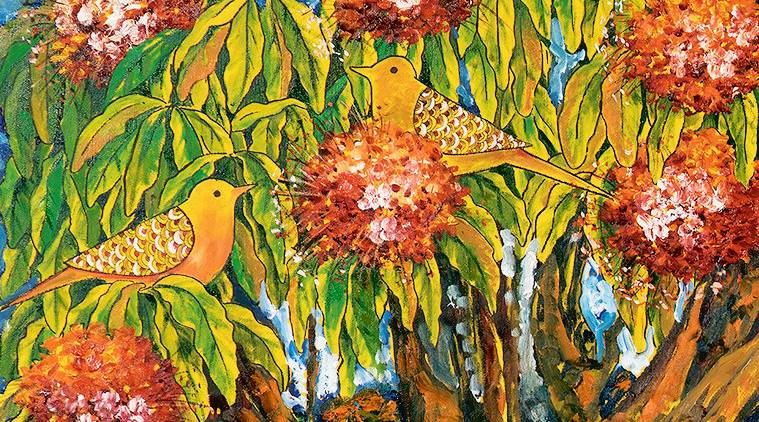

Earth to earth: Ashok Vatika, oil on canvas, 2018, by Jayasri Burman, where the artist visualises Sita as Dharitri, born out of mother earth, and malleable like earth, a woman strong enough to bear her ‘traumatised life’.

What can possibly be said about the First Lady of Indian myth that hasn’t been said before? Whether we love her or hate her, revere her or reinvent her, see her as archetype or stereotype, she’s seared her way into our psyches and imprinted herself on our DNA.

My early response to Sita was pity. Dignity and strength of character, she had in plenty. But truth be told, I found her somewhat insipid. A puppet of circumstance. A victim of fate. A pawn in the hands of licentious men, whimsical family politics, duty-bound monarchs and gossip-mongering commoners. I wished she had displayed the more obvious spunk and human passion of Draupadi.

Much of the time, Sita seemed to meekly follow dharma, rather than wrestle with it or reshape it. She provoked tumultuous events in other people’s lives, but seemed to have little responsibility over her own. She seemed more marionette than architect of her own destiny.

As I grew older, Sita bothered me for a deeper reason. World folklore and myth is replete, as Joseph Campbell shows us, with figures of the male questor hero. But women’s interior life seldom became the stuff of mythic drama. I grew interested in Sita’s journey. Who was she? Where did she really belong? Did she ever find out?

Unsurprisingly, she is immune to the charms of Lanka, the place of her captivity. But for all her love of Ram, did she ever really belong in Ayodhya? With all its palace intrigue and hothouse family politics, did Ayodhya simply spell another kind of captivity? And what of her natal home, Mithila? Perhaps, she was freer there. But exactly how free? She was evidently happiest in the Panchavati forest. That interested me. As the daughter of Bhuma Devi, the Earth Mother, is it any wonder that she preferred a natural forest landscape to the artificiality of life in court? I began to wonder if Sita’s real tragedy lay in being catapulted into a daytime world (the Raghuvanshis were of the solar dynasty) that showed little respect for the darker, more profound subterranean wisdom she represented. Was she a symbol of an organic harmony that the human race is still hell-bent on desecrating?

This was more than an ecological story. This was existential, too. In many ways, Sita mirrors another great classical heroine, Shakuntala. Both are reared by foster parents. Neither belongs entirely to this world. Both have deeply unfulfilling love lives. Both are single parents to (later famous) sons. Both are conflicted about their address, never full-time residents of court or forest (They’re both Aadhaar-card nightmares, in short). Both don’t belong fully anywhere: either to their father’s homes or their husband’s. Both have distant mothers. One’s mother is the earth goddess (ever-present but so often forgotten), the other’s mother is a denizen of the celestial realms, Menaka.

As their lives oscillate between court and hermitage, earth and sky, where do Sita and Shakuntala really belong? Their social contexts do not allow them to ask this question. But if they are to speak to Indian women today, they must be invited to rewrite their stories, to draw their own maps home.

Some years ago, I wrote a poem cycle on Shakuntala. I was bothered by her lack of agency, and her sense of unbelonging (as I was by Sita’s). She seemed one hell of a confused woman — and (as the daughter of a sage and an apsara), a genetic calamity. But towards the end of the poem cycle, I suddenly realised that Shakuntala was, in fact, a tremendous possibility, not a liability. Standing on the margins, she had a vantage point from which she could view two different worlds. In a world of plurality, this woman of multiple homes and multiple citizenships was a winner!

In the poem, I imagined Shakuntala’s ideal world as one in which everyone she loved clustered joyfully into the same frame: her rishi father, her apsara mother, her ardent lover, her beloved deer, her two women friends. And in that ecstatic scene of integration, a deep inner split would be healed: between heart and head, body and beyond, earth and sky, maternal and paternal legacies, natal and marital worlds, innocence and experience.

Similarly, if Sita were to write her own script, what would she choose? Janaka’s enlightened paternal care or her birth mother’s earth wisdom? Ram’s loving arms or the Earth Mother’s nurturing womb? Mithila or Ayodhya? The urban landscape or the Dandaka forest? The answer, I imagine, is both. And in making her peace with these realities, she would begin, finally, to dream her own dream.

As the daughter of the Earth married to a scion of the solar dynasty, Sita can be seen as the conflicted woman, torn between polarities: nature and culture, earth and sun, terrestrial and aerial, right and left brain, samsara and nirvana. But when empowered, the same woman can turn into bridge, hyphen and corpus callosum between disparate worlds. Sita is an invitation to integrate, to heal and make whole. She understands the darkness of the earth cave and the light of civilised existence. Hers is a dual wisdom we desperately need in today’s fragmented world.

The ancient existential error so many protagonists have made is to forget their place of origin. Shakuntala leaves the forest for her fickle lover in court. The Little Mermaid chooses human love and forgets her aquatic antecedents. Sita is in tune with deeper natural rhythms, but is tamed by the patriarchal dharma of her times. And so, the wild, dynamic, compassionate goddess that lurks in every woman is domesticated in different ways.

It is time for a new script. Time for heroines to stop walking on glass, and re-enacting fire ordeals. Time for them to stake their claim to their own histories. We cannot polarise our worlds any more. The time for “either-or” is over. We need our place of origin and our place of destination — even if we eventually find there’s not much difference between the two. We need earth and sky, forest and court, mothers and fathers, natal and marital families, nature and culture. There can be no Ram Rajya in which Sita is not an equal partner. That equality needs a patient Ram, but also a wise and responsible Sita.

Sita’s dharma today is to follow her own path — her swadharma. In doing so, she doesn’t reject Ram. She includes him. She transforms him. But first, she has to realise that her answers will never be found in either Ayodhya or Panchavati, with her Earth Mother or with Ram. She is the place where all binaries meet. She is her own address, her own sanctuary, her own answer.

The Ramayana begins with the story of two mating birds being separated by a hunter’s arrow. That image marks the birth of duality, of samsara. That fracture is not healed. For the Uttara Kanda (even if a later interpolation) separates Ram from Sita in an unsatisfying close to a great love story. The ultimate relationship, however, is the union not of two halves, but two wholes. If the two birds are to come together again, Sita must be heard. There can be no Ram Rajya without Sita’s wisdom.

Arundhathi Subramaniam is an award-winning poet and writer on spirituality and culture.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario