His Portion of the Earth

Sir Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul’s ambition was to be a writer, and, in this, his legacy — shaped by the curious cultural ecosystem he found himself in — will endure beyond his politics and his often acerbic public personality.

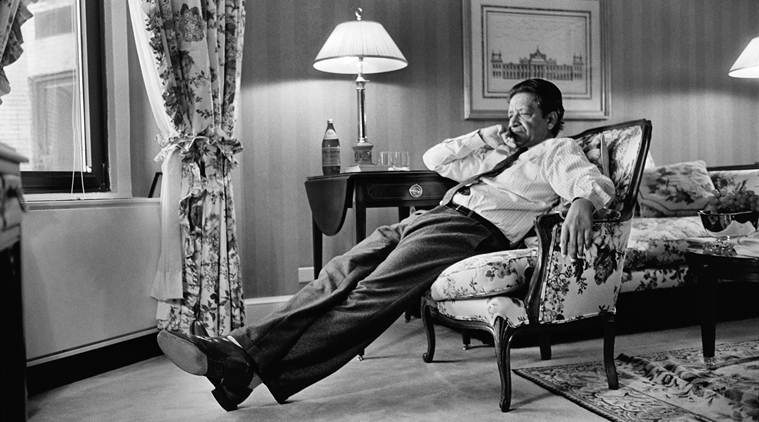

The writer and his world: VS Naipaul at the Westbury Hotel in New York on January 24, 1991. (Photo: Neal Boenzi/The New York Times)

On learning that the shrewd French diplomat Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord had died, Prince Metternich is said to have enquired: “What did he mean by that?” I had a similar thought a fortnight ago when news came of VS Naipaul’s passing, a few days short of his 86th birthday. The feeling of enduring permanence that Vidia Naipaul evoked, I realised later, came from the extent to which his mind was ever present in his books. For a lifetime, he had hedged against extinction; like Mr Biswas when he got his house, he laid claim to his portion of the earth.

He made it clear from the start that his books were not written in order to be praised too widely: his writing had to, in his word, abrade. It had to draw a response. In recent weeks, there have been homages and anti-homages, some ascribing a personality to Naipaul that bears no resemblance to my memories of him, or to the sensitivity of his writing about the traumatised lives of others. One newspaper even published a final interview with Naipaul that was faked, an inadvertent tribute perhaps to the hustler in his book The Middle Passage, who sold tickets for a fictitious concert by the soul singer Sam Cooke, and promptly disappeared.

A response that seemed to understand uncannily what Naipaul had achieved in his writing came from another writer, Arundhati Roy. In answer to a question from the Johannesburg Review of Books, she said: “If somebody equates me with Naipaul as a writer of equal power but with completely different politics, I can’t think of a greater compliment.”

Barack Obama, who first entered our consciousness as a memoirist rather than as a politician, made an equivalent point. “I think that there are writers who I don’t necessarily agree with in terms of their politics, but whose writings are sort of a baseline for how to think about certain things — VS Naipaul, for example,” he told the critic Michiko Kakutani a few days before stepping down as President of the United States. “His A Bend in the River starts with the line, ‘The world is what it is; men who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it.’ And I always think about that line, and I think about his novels when I’m thinking about the hardness of the world sometimes, particularly in foreign policy, and I resist and fight against sometimes that very cynical, more realistic view of the world. And yet, there are times where it feels as if that may be true.”

Now, in the hyper-real age of Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Bashar al-Assad, it feels truer than ever. Obama marked Naipaul’s death by rereading A House for Mr Biswas, and described it as “his first great novel about growing up in Trinidad and the challenge of postcolonial identity.”

The West Indian childhood, and its mark on the protean writer and public personality that Naipaul became, has, since his passing, received less notice than it deserves. He enjoyed, to use a Trinidadian phrase, “chooking fire” — poking the embers, adding fuel, vice-signalling. A year or two after I published my biography of him, The World Is What It Is, I went to Trinidad for the Bocas literary festival. One afternoon, I received a visit from a delegation of four or five elderly men of Indian descent from Chaguanas, a region in the island’s former sugar belt. They were Sir Vidia’s childhood friends, they said, and wanted to know why he had got so much credit and attention for writing A House for Mr Biswas. “Any of us could have written that book,” said one, who was acting as a spokesman for the group, and looked like Naipaul, although he said he was not a relation. He presented me with a worn manuscript: it was his own book about the world of their childhood, done in fractured English.

All writers are created by their own talent, but also by a surrounding cultural ecosystem: the family, friends, schooling, a society that values or ignores the written word. Naipaul was raised in the 1930s in a poor extended family in rural central Trinidad, which was, at that time, a Crown Colony (significantly different in its political structures, its scale and its opportunities to the Indian empire of the time). His grandparents, and the surrounding community, had been shipped from India in the late 19th century as indentured labourers after the abolition of slavery in the British empire. It was a brutal way of life, cutting cane, and literature was nowhere. Three out of four East Indians in Trinidad at the time of Vidiadhar Naipaul’s birth were illiterate. As he said to me: “We were surrounded by language that came from the days of slavery. Parents would say: ‘I will peel your backside. I will make you fart fire.’ You can hear the language of the plantation.”

People spoke Trinidadian Creole, a version of English with loan words from many languages, or a locally-adjusted version of Bhojpuri, a language from India’s United Provinces. His father, Seepersad, had escaped a likely future as an agricultural worker by teaching himself English and becoming a reporter on the Trinidad Guardian. They moved to St James in the capital, Port of Spain, a rough district known as “coolie town”. Implausibly, father and children read John Stuart Mill, Gustave Flaubert, Mary Wollstonecraft and JS Van Teslaar on psychoanalysis. Their mother Droapatie, who was semi-literate, insisted all her seven children studied hard. A black colleague on the newspaper remembered Seepersad as “basically a rural Indian, not a town Indian.” People like him were expected to do street-vending, carry head-loads or collect garbage, and when Vidia went to a Port of Spain school, he was one of the few Indian students.

From this inauspicious colonial background, he went on to develop a uniquely precise descriptive command of the English language.

The reason I mention the delegation from Chaguanas and the world into which Naipaul was born is as a reminder of the extent to which he was created by the West Indies. Britain, India, the world of literature — all have sought to claim or reject him. He was himself responsible for this. When he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2001, he praised “England, my home, and India, the home of my ancestors.” Why no mention of Trinidad? “It might encumber the tribute,” he said with a wicked, asthmatic laugh. As his contemporary, the Barbadian writer George Lamming, said at the time, Naipaul was masquerading or “playing ole mas”, meaning that he was needling people for his own entertainment. In this, as on many occasions, he was remaining true to his origins by striking the first banter blow. The only other person from St James to have made it on the world stage is the attitudinal rapper Nicki Minaj, who, like Naipaul, is known for taking no prisoners.

He came from a community that was, in his father’s words, “too much of a majority to assimilate, too much of a minority to dominate.” As an East Indian West Indian, Naipaul was not alone in feeling alienated by the Black Power Movement of the late 1960s in the newly-independent nation of Trinidad and Tobago. His subsequent superficial embrace of the public role of an old-school English gentleman was in part a defensive move, a mechanism to mask himself while he got on with writing 30 remarkable books, most of which in one way or another were concerned with his own triangulated, transcontinental origins. Richard Drayton, the Rhodes professor of Imperial History at King’s College London, has rightly described Naipaul as “the jilted lover of the Caribbean nation.”

If you are liable to be offended by words, Naipaul provides a cornucopia of source material. In his case, there is no need to trawl through deleted social media posts in search of possible outrage: every time he appeared in public or gave an interview in the course of a literary career that lasted for almost seven decades, he was liable to throw out a few insults touching on race, gender, religion, mental capacity or physical appearance. These comments were substantially less subtle than his body of published work.

In interviews with me for The World Is What It Is, Naipaul was extraordinarily frank about his own bad behaviour, and, in particular, the way he had treated his first wife, Patricia, and his girlfriend, Margaret Murray. This confessional mode was an intellectual choice — since he believed the truth needed to be told — although it was one that caused him subsequent regret. It would be wrong, though, to assume that rudeness was his default style. In an interaction with a random person, he was just as likely to be kind and sympathetic as he was to be offensive. He could, however, never be indifferent, and his likes and dislikes were unpredictable.

I believe no writer of the last half century has been as acute as Naipaul in diagnosing how and why societies go wrong. It does not mean he always got things right: he could be over-pessimistic, the plots of his novels were often cursory, and his women characters were thinly drawn. There was a tormenting and tormented quality to his analysis. But when he saw intuitively inside a place or a person, the effect was uncanny. Time and again when interviewing people who had known Naipaul, they told me how he had done what he called a “face reading” of someone he had met, and deduced their life and character with chilling accuracy. He had a lethal eye and ear, particularly for self-delusion. As a character says in one of his books: “The only lies for which we are truly punished are those we tell ourselves.” Although his politics may have been different, his insights into the psychological effects of imperialism can be read alongside those of Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Frantz Fanon.

Ngugi, a writer whose work Naipaul admired, understood this. Baptised James Ngugi, he stopped working in English and now writes in Gikuyu; he appears to be at some distance from Naipaul. Yet, they found a point of connection. In a tribute, Ngugi recalled how, late in their careers, the two men had met over a literary prize in Italy. How, he asked Naipaul, did he have the confidence to write about countries that were new to him? “I always feel I don’t know enough,” Ngugi told him. Naipaul asked him to look across the table “piled with all the delicacies of the celebratory dinner. I did not see anything beyond the colours of the cloth, the flowers, and the cutlery, all which matched in a kind of glittering grandeur.” He identified a flower that was at odds with the tableau, and made it his subject. “The odd defines the norm. Maybe Naipaul was right. In cinema, the single individual moving in the direction opposite that taken by the crowd attracts the eye of the viewer but helps us realise the crowd size,” Ngugi wrote in the tribute.

Vidia Naipaul’s ambition was to be a writer. On the journey from Chaguanas to the Nobel Prize, he sacrificed anything and anybody that got in his way. His legacy is his books, and he should be judged for them. I have no doubt they will endure.

Read The Enigma of Arrival (1987) to see inside a life of displacement and migration, when an individual shifts from the Caribbean to rural England. Read The Middle Passage (1962) to recognise the legacy of slavery and the destruction of indigenous civilisations. Read In A Free State (1971) to understand group identity and structural inequality. Read Guerrillas (1975) to see the self-deception of revolutionaries and their enablers. Read The Suffrage of Elvira (1958) for fun. Read A Bend in the River (1979) for a prophetic view of conflict between communities in a newly independent African country. Read India: A Million Mutinies Now (1990) for an anticipation of India’s later social upheaval. Read Among the Republicans (1984) for an insight into the fantasies of the American right. Read Among the Believers, where, as early as 1981, Naipaul anticipated the rise of Islamist extremism as a revolt against the limits of secular nationalism. Read The Mimic Men (1967), an ironic novel showing the intolerable pressures on the leader of a postcolonial nation which depends on Western modernity, even while rejecting it. Read A Way in the World (1994) for a study of the self-manufactured tricksters of the West Indies. Read Miguel Street (1959) for a child’s eye view of street life in Port of Spain.

VS Naipaul will be read globally for centuries to come by those who seek to understand the end of the European empires.

Patrick French is Dean, School of Arts and Sciences and Professor for the Public Understanding of the Humanities, Ahmedabad University. He is the author of The World Is What It Is: The Authorised Biography of VS Naipaul.

.png)

VS Naipaul in Wiltshire, England, circa 1975. (Courtesy: McFarlin Library)

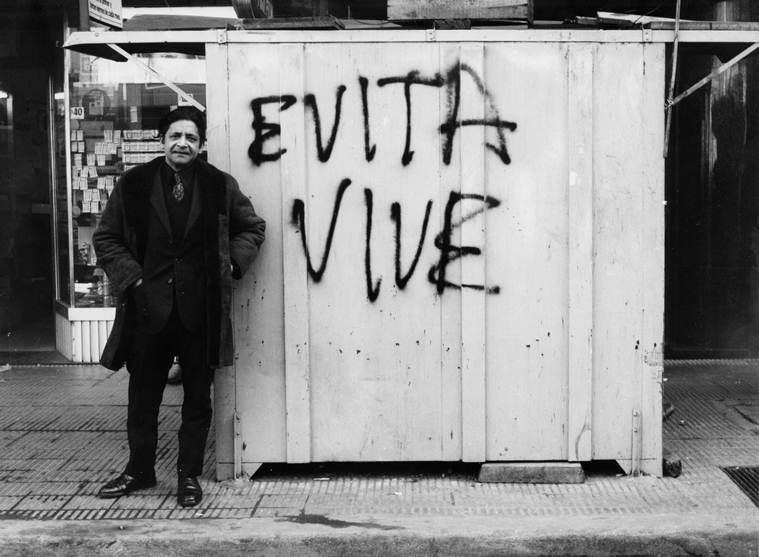

VS Naipaul in Wiltshire, England, circa 1975. (Courtesy: McFarlin Library) VS Naipaul in Buenos Aires in 1974.

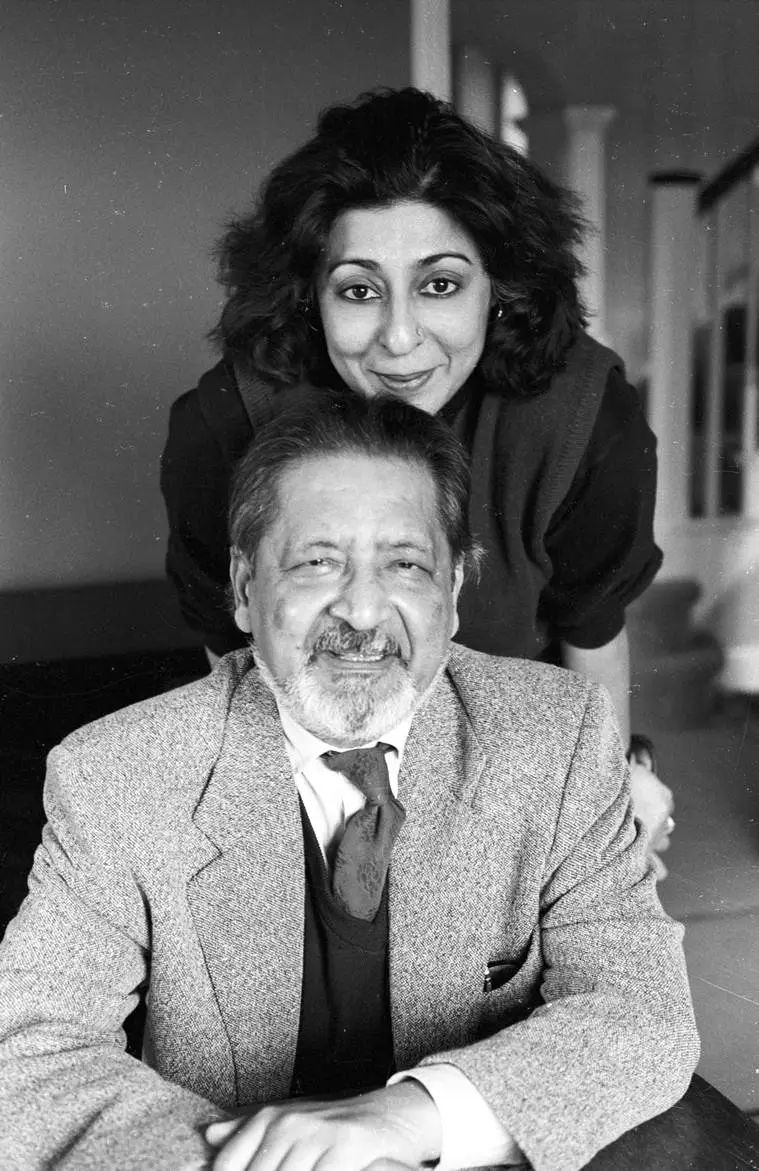

VS Naipaul in Buenos Aires in 1974. Inner circle: Naipaul with his wife Nadira, 1999. (Photo: Jerry Bauer)

Inner circle: Naipaul with his wife Nadira, 1999. (Photo: Jerry Bauer)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario