Chinese cloisonné: A beauty of 700 years

Chinese cloisonné is a kind of enamelware, or rather, copperware model decorated with filigree and enamel. Its craftsmanship reached its apex in the Byzantine Empire and reached China in the XIII century. How did cloisonné enter China and how did its craftsmanship in Beijing become unrivalled in the world?

The moment you step into the museum, your eyes will be caught by a huge stout jar for its gorgeous brilliant colours. Against the sky dyed in sapphire and peacock blue, a golden Chinese dragon is roaring, with its scales shimmering and its body surrounded by a dark red colour as if it’s spitting fire. The dragon’s feelers and tail are tinted in black ink and the clouds sketched in bright yellow are filled with blue and red colours. Although very colourful, the jar is also stately. The rim bears two marks of identification which read “Made in the reign of Emperor Xuande of the Ming Dynasty” and “For Royal Use”. Without doubt, what you are looking at is a piece of the Chinese cloisonné.

Chinese cloisonné is a kind of enamelware, or rather, copperware model decorated with filigree and enamel. It originated in the Near East in ancient times and its craftsmanship reached its apex in the Byzantine Empire. In modern times, Western interest in the cloisonné was rekindled in 1904 at the St. Louis World’s Fair, where works of Chinese cloisonné won first prize. At the Panama–Pacific International Exposition held in San Francisco in 1915, the Chinese cloisonné defended its honour, making it well-known around the world.

How did cloisonné enter China and how did its craftsmanship in Beijing become unrivalled in the world? The Palace Museum in Beijing has the world’s largest collection of cloisonné. Physical evidence indicates that cloisonné began to be appreciated by the emperors of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). With the imperial court of successive dynasties devoting massive human and material resources to making exquisite cloisonné, it flourished in the court for over 600 years. For a long time, cloisonné was a symbol of the imperial family. Today, when you visit the Palace Museum, you will be able to see elegantly designed, beautifully coloured and exquisitely crafted works of Chinese cloisonné in almost every hall. However, the name /jĭngtàilán/ ‘jingtai blue’ did not appear until the reign of Emperor Yongzheng (1723-1735) of the Qing Dynasty, when it became fashionable to copy the cloisonné of the景泰/jĭngtài/ period in the Ming Dynasty and inscribe the characters 景泰 on it. Since the most common colour of enamel glaze was peacock blue, and the Chinese character 蓝/lán/ ‘blue’ is similar in pronunciation to the character 琅/láng/ of 珐琅/făláng/ ‘enamel’, the name 景泰蓝 came into being.

The Chinese philosophy of making wares is intriguing. As is reflected in making Chinese cloisonné, it has two outstanding characteristics:

- First, the craftsmanship of the artisans is perfected to its utmost level. Chinese cloisonné is made completely by hand through a complicated and sophisticated process consisting of six main steps, including making the copper body, filigreeing, colouring, firing in a kiln etc. In fact, on more detailed examination, there can be up to 108 steps. As mentioned above, the complicated decorative patterns on the cloisonné jar made during the reign of Emperor Xuande of the Ming Dynasty was produced by filigreeing. A pair of tweezers was used to twist fine flattened copper wire into the patterns of the dragon’s body and claws, and the clouds in the sky, which were then stuck to the body of the jar before enamel glazes of different colours were filled into the resulting lattices. Fired in a kiln, they became the colourful patterns we now see. A piece of copper the size of a drop of water can be stretched into a thin wire of 2 meters long, 1 millimetre wide. The wire needs to be shaped into various patterns, usually through seven to eight twists and turns, sometimes even over dozens of twists and turns. Filigreeing demands great patience and perfect craftsmanship. The copper-wire patterns have to be identical with the original design. Otherwise, when they are filled with enamel and fired, they will look stiff and lifeless.

- Secondly, the culture of making various wares in China attaches great importance to the harmonious relationship between man and nature. When the copper-wire patterns are ready, they have to be stuck to the copper body of the ware. This is done not with some high-tech glue but with bletilla striata—a species of orchid which is also a kind of traditional Chinese medicinal herb. For its very high viscosity, bletilla striatais an excellent adhesive agent; more importantly, in the process of firing, chemical glues will leave some residue which may affect the quality of the cloisonné, while bletilla striata, as a natural plant, will leave no trace after firing.

A national treasure

The tradition of Chinese cloisonné has survived for more than 700 years, during which time it has gone through ups and downs. Whenever it was in a period of decline, there were always members of the literati or craftsmen to ensure the survival of this national treasure. In the late Qing Dynasty, the crafts of making cloisonné began to leak out of the imperial court. Private workshops were established to make cloisonné. In the last years of the Republic of China, social upheavals made it difficult to obtain all the extremely high-quality raw materials and there was also a shortage of craftsmen. As a result the quality of the products was declining year after year and this traditional craft was facing its demise. In 1951, Ms Lin Huiyin, a prominent architect and designer, who occupies an important position in Chinese cultural history, led a couple of female art students in setting up a group for saving Chinese cloisonné. Working with elderly craftsmen on a daily basis, they studied the traditional techniques and, step by step, turned them into a standardised modern process. One of the girls was Qian Meihua, who later became a grandmaster of cloisonné craftsmanship, and the group for saving Chinese cloisonné later developed into today’s Beijing Enamel Factory, which is well-known at home and abroad. Since 2005 Beijing Enamel Factory has started to duplicate cloisonné treasures of The Palace Museum. Visiting the factory museum on the second floor of the building, we were at once brought back to the royal court in Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties by the elegant sapphire blue octagonal incense burner, kylin and vases decorated with dragon patterns. Mr Zhong Liansheng, Qian Meihua’s student, the current chief artificer of the factory told us that the duplicates should be very similar to the originals in techniques and overall dimensions. By doing this they trace the history of cloisonné and inherit the essence of craft .

Artistically, breakthroughs have been made in contemporary cloisonné making, fortifying its Chinese characteristics. This is because Mr Zhong Liansheng overcame the technological difficulty of “leaving blank”, which posed a daunting challenge to the old masters. The Chinese art has extreme high regard for the idea of “leaving blank spaces”. “Blanks” are often employed by Chinese artists and calligraphers to set out the intended aesthetic effect. Yet the big blue Xuande cloisonné jar has very complex patterns, as do each and every cloisonné piece from the Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties. As mentioned previously, the patterns on a cloisonné ware are created by filigreeing. “Leaving blank” means no patterns or no filigreeing, but simply applying large areas of enamel glaze, which, after firing, will fragment into small pieces like broken glass, losing the aesthetic effect. Through a unique technical process, Zhong Liansheng overcame this difficulty. His work A Dream of Lotus Flowers brings the Chinese ink and wash technique onto a vase and a jar. After firing, large areas of blank on the body remains shiny and smooth, creating an unprecedented kind of elegance and refinement, unique of its kind.

Three Steps to buy Chinese cloisonné:

First, feel the weight of a cloisonné work by hand.A fine cloisonné ware usually has an adequate amount of copper.

Second, get a feel of it by caressing its surface.

The copper wire and enamel glaze should be adhered to each other seamlessly. A smooth surface indicates that the artisans have polished the article with extreme care.

The copper wire and enamel glaze should be adhered to each other seamlessly. A smooth surface indicates that the artisans have polished the article with extreme care.

Third, observe the details of the patterns.

Only a work with even colours and a gradual transition of one colour into another, and with no air bubbles can be regarded as a fine piece.

Only a work with even colours and a gradual transition of one colour into another, and with no air bubbles can be regarded as a fine piece.

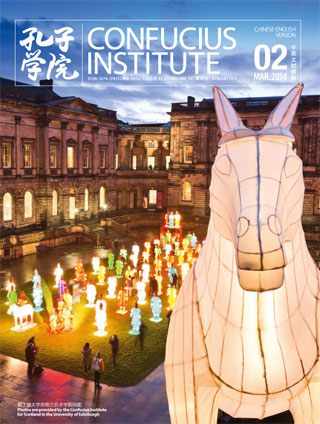

Published in Confucius Institute Magazine.Number 31. Volume II. March 2014.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario