Written by Parth Khatau |Updated: December 3, 2018 1:45:44 pm

Chronicler of his times

Historian JRB Jeejeebhoy’s writings compiled in the just-released book Bombay Vignettes documents little-known stories of the island city.

In the late-18th century, when the British East India Company had established itself as a political power in India, slaves were not uncommon in the areas over which they ruled. JRB Jeejeebhoy, a Bombay historian, whose writings got published in various newspapers in 20th-century Bombay recorded the presence of slave trade in the city, in the Anglo Gujarati newspaper Sanj Vartaman.

“According to Sir Bartle Frere, Governor of Bombay from 1862 to 1867, the total slave population in British India in 1841 was between 80 and 90 lacs. Now the slaves liberated in the British Colonies on August 1, 1834 were estimated between 8 and 10 lacs, and those in North and South America in 1865 at 40 lacs so that the number in British India far exceeded that in the British Colonies and America put together. When brought to the notice of the Commissioners appointed to frame a code of conduct of criminal law in India, the necessary legislation was passed and by Act V of April 7, 1843, slavery ceased to exist by law in all parts of British India,” Jeejeebhoy wrote.

This article is one of many which sheds light on little-known facts from Mumbai’s history and which have been collected in a new book called Bombay Vignettes. Edited by city historian Murali Ranganathan and published by The Asiatic Society of Mumbai, the book is a collection of Jeejeebhoy’s writings and was put together over the last two years. “I have been following his work for 12 years. When the Asiatic Library came up with the idea of reprinting archival material instead of publishing fresh material, I thought this would go well with the project,” he said.

Jeejeebhoy was a columnist for various publications such as The Times of India, Bombay Chronicle, Bombay Courier and Sanj Vartamann. Ranganathan sourced much of his material from the Asiatic Library, which has full runs of The Times of India and Bombay Chronicle and many others in and around Mumbai. “Sanj Vartaman, a Gujarati newspaper from back in the day, was sourced from Baroda,” said Ranganathan, who began work on the book in November 2016.

As a man of varied interests, Jeejeebhoy’s writings too covered a wide range, touching on different aspects of the city — the menace of rash driving, the slave trade, witchcraft, and the Parsi community, to which he himself belonged. An heir of the Byramji Jeejeebhoy family, which owned textile mills and heavy industries, Jeejeebhoy also touched upon women empowerment, particularly issues that women in the Parsi community faced back then. He also wrote extensively about Mumbai’s legal history, covering conflicts between the bench and bar and Bombay High Court’s first Indian judge, Janardhan Wasudev, who was appointed in June 1864.

Putting together this material in a cohesive form was a challenge, says Ranganathan. “I had to make sense of a huge mass of articles and publish them in a way people could understand and for that, I needed a good flow,” he added.

The first part consists of the city’s vignettes and contemporary concerns, followed by writings on the judicial and legal institutions of Bombay, important colonial personages of the city and lastly the Parsi community in Bombay.

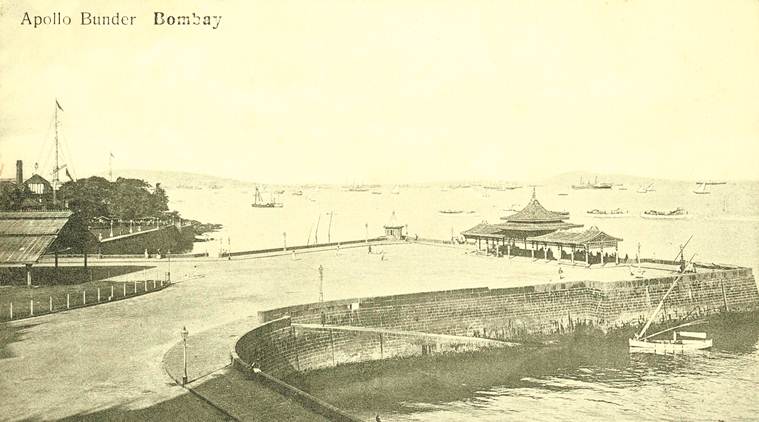

“All the writings were under copyright until 2020 and we are grateful to the Jeejeebhoy family for giving us the permission to publish them,” said Ranganathan. The book consists of 40 illustrations, most of which were sourced from the Asiatic Society of Mumbai. “None of Jeejeebhoy’s original publications had pictures but I picked those that complemented them best,” said Ranganathan.

The city, whose history he so diligently chronicled, however, has little knowledge of the historian today. Ranganathan explains that this is because Jeejeebhoy, whose writing were scattered across various newspaper columns, himself never attempted to collect his work into a single volume. “The archives today are very hard to find and a lot of them are in pretty bad shape,” says Ranganathan, who also said that around 40 per cent of his writings are still not available. “We have done everything to not preserve our structures. It was something that Jeejeebhoy was affected by too, as we find in his writings. When it comes to archives and family records, the newer generations of the families do not know much about them and do not possess the wherewithal to preserve them,” he says.

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario