I chose to be loyal to the place where I am guilty, helpless and alone: Author Feroz Rather

Author Feroz Rather on his first book, and on the Valley being a living entity in his fiction — both in its beauty and violence.

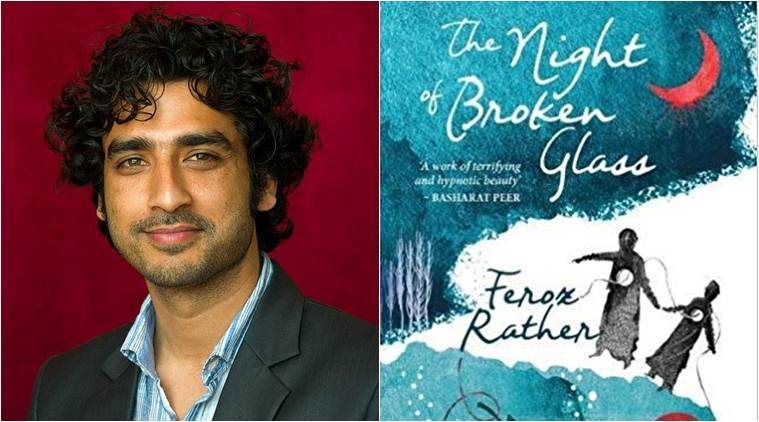

Voice from the valley Feroz Rather (left); his debut novel.

There comes a moment in Feroz Rather’s The Night of Broken Glass (HarperCollins India) — a collection of short stories based in and on Kashmir — where a young Ilham, upon watching another young Kashmiri being tortured, says, “I realised that it made me neither sad nor angry.” It’s a rather simple line left to carry a very difficult resignation.

“Ilham is a ghost, remember?” Rather, 34, and based in Tallahassee, Florida, US, where he is now concluding his PhD in creative writing points out, reminding me that the resignation belongs to a man who is already dead. A vital detail that I had forgotten so easily in that particular moment because the same resignation is now finding its way towards those of us still alive in Kashmir. Ilham’s is a nervous condition: a helpless yet defiant dead man who shrugs at the violence that once killed him but also refuses to treat himself as dead. Today, the same nervous condition occupies Srinagar, where the streets are open and loud but the air reeks of death and its silence.

Rather’s literary debut makes an intimate yet scathing portrait of Kashmir that belongs as much to our future as it does to our past. Edited excerpts from a phone interview:

Kashmir may have claimed itself as your subject almost instinctively but how did you arrive at knowing how to treat that subject?

One is tempted to report facts and tell the ‘true’ story of Kashmir, given the magnitude and consistency with which violence is inflicted on us. But one is also tempted to go away from what is immediate and historical and write fiction. For me to have convinced myself that fiction is the medium through which Kashmir should be written took a very long time. The realisation that fiction was not about reporting and replicating the brutalities and injustices but rather about charting the selfhood of the people who suffered and witnessed did not come easily.

And what did it mean to write fiction about Kashmir?

I think to write fiction about Kashmir is to make sense of how the rhythms of the civilian life have been disrupted by violence. To question who we are, historically and metaphysically. To question what has happened to us, and where are we being led. To portray the desolation — that strange sense of restlessness — that each of us inhabits because of how we have been manacled and subjected to a walled existence.

You wrote the book between 2015 and 2017 in the US, where you have been completing your PhD in creative writing. Did you seek the distance from Kashmir, for the book?

It should not be surprising if I tell you that I am a bad sleeper and my dreams are almost always about Kashmir. I have this premonition that one day I’ll wake up to very bad news about home and the news will vindicate the nightmares that I’ve had during the night.

I seek distance but the darkness is near. I don’t know if I should call it a meditative distance that Tallahassee has given me from Kashmir but it did create strong illusions of space to introspect. It allowed me to explore the selfhood of the characters, which is only possible if you can contemplate them in the first place. Having said that, it is also true that since things are so grave in Kashmir, I feel that even if you just replicate them without developing the conflict, for the outside world, they already have a force of fiction. A poet who lost all his poems because militants happened to hide in his house and the soldiers razed it down to ground, a journalist who heard that someone has been killed in the neighbourhood and then realises the person to be written about is no one else but his own brother, a doctor who operated on his young son’s bullet-torn body couldn’t save him. It cannot get more ironical than that.

What role does Kashmir play in your relationship with literature?

I don’t think of them separately. Kashmir has shaped me in a particular way to see the world and the opposite is true as well. One of my American professors once told me that the problem with my book is that it’s written from and towards Kashmir. I did not fight him. Secretly, I felt good about Srinagar being the city that is central to my world. Life as it is lived there is how I interpret the world.

The notion of beauty is incredibly subjective. Are the moments of profanity in your stories a reflection of your perception of beauty?

I do see a lot of beauty in the profane and I was willing to go where our society pretends not to go. In Kashmir, we don’t really acknowledge discourses about sexuality but writing about the body is only an expression of our own humanity. I wanted to make myself conscious of the body — the beauty of the body — and to not be ashamed of it. Beauty would be too neat without being profane.

Violence enters and leaves the pages of your book deftly, without any forewarning or resolution, much like how it has disrupted life here in Kashmir. How did you go about characterizing violence?

My pursuit, at a subconscious level, was to humanize violence and to explore what it means for a powerful military man to inflict mindless violence on people — to stuff shoe polish in someone’s mouth or to break a shopkeeper’s jaw. ‘The Nightmares of Major S’ went beyond the surface portraiture of violence, and into the individual and his motivations and background.

At a linguistic level, there was also a desire to wreak some creative violence with the language itself. In writing the book, I was trying to portray Kashmiri reality in English. So, it was a lot like immersing characters into a language where they are homeless—spiritually estranged. If you come into the English language from outside, I suppose that creates weird language structures and places a certain pressure on the syntax as though within its bounds English cannot neatly accommodate Kashmir’s cultural reality. I felt that pressure in ‘The Boss’s Account’, where the boss contemplates the pasture and the sentences become long and unwieldy.

I did find myself noting the places in which you surrendered to Kashmiri altogether — the points that pressed you back into your own language.

Yes. All these characters are also adrift, right? They’re all moving. It is probably my own spiritual homelessness in English that informs the restlessness of my characters.

Writers are fiercely protective about their freedom. Loyalty is equally significant in anchoring them in the act of writing. What did you choose to stay loyal to?

I chose to be loyal to my own willingness to witness the act of brutal violence as it is inflicted on the body of a human being in Kashmir. I chose to be loyal to my own vulnerability, and my uncertainty. I chose to be loyal to the place where I am guilty and helpless and alone.

Niya Shahdad is a writer from Kashmir

.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario