My Lord’s not My Shepherd

Essays that underline Indian governance-democracy’s need for divine help in the face of multiple crises

A view of Supreme Court in New Delhi (Express photo by Ravi Kanojia)

Written by Rajeev Dhavan

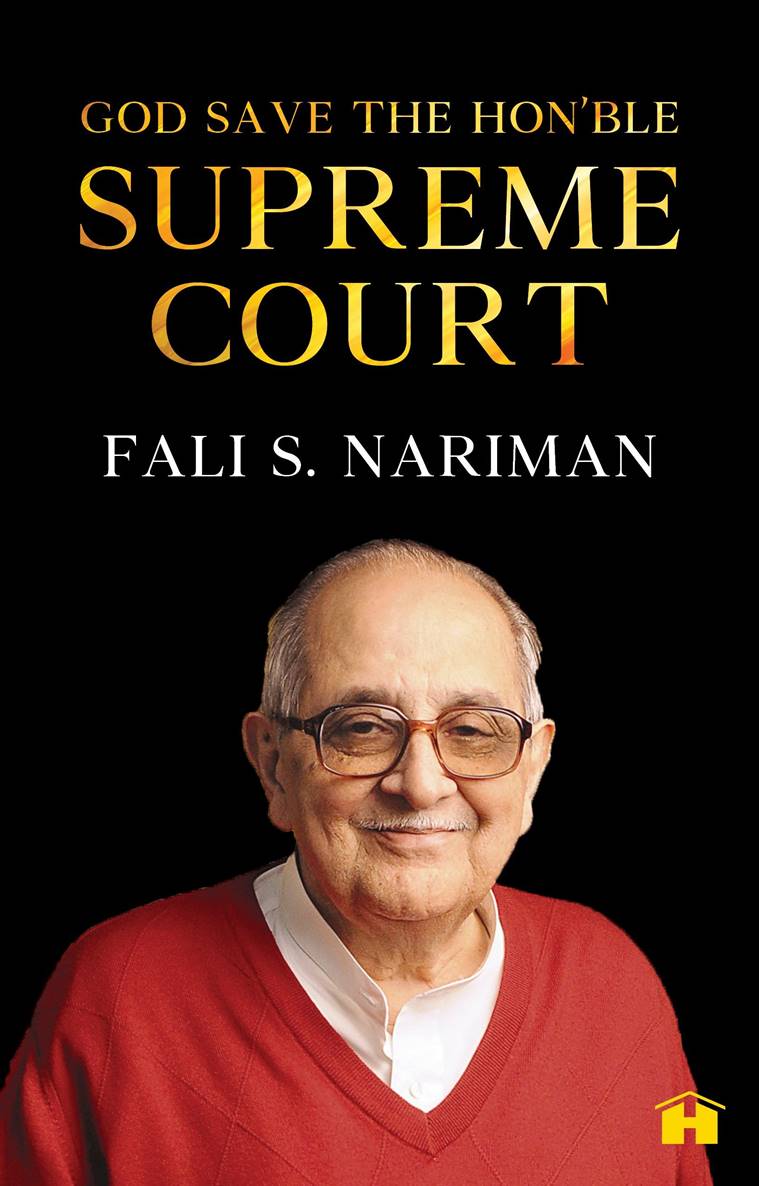

Fali Nariman is the greatest lawyer-jurist of our time. When the Emergency began, he resigned his post as Additional Solicitor General. Reacting to Gujarat’s treatment of its Christians, he gave up the state’s Narmada brief. In his reminiscences, Before Memory Fades (2012), Nariman had wondered in retrospect that, perhaps, he should not have taken up the Bhopal case for Union Carbide. Appointed to the Rajya Sabha as a nominated Member of Parliament (MP) by the Vajpayee government in 1999, he remained a neutral private member. Faced with the dilemma of practicing in court and discharging his duties in Parliament, Nariman gave up his practice so that he could attend to his parliamentary duties. When asked in a TV interview whether he wished he had done more in Parliament, he replied in the affirmative. His private member bills did not get government backing. But he became a nodal point for advice that was not politically slanted.

He has been an amicus appointed by the Supreme Court (SC) in many matters; and has freely taken up pro bono briefs — the last of which was the Rohingya case. Whenever matters come into the public domain, he gives his forthright views. But unlike many others, he does not seek publicity through chat programmes. As a commissioner in the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ-Geneva), he recommended me as a successor when he could have easily recommended a relative. Therefore, it is necessary to get the measure of Nariman as a statesmanlike jurist before we approach this book. Lawyer MPs who rush from court to court chasing cases, and what goes with the chase, may do well to consider Nariman’s advice that legal practice and Parliament are both full-time jobs.

This is a book of essays, but some seem a bit like scrapbook entries, with each scrap up for comment. The very first chapter is a series of judgments between 2016–2018 in which the Supreme Court delivered five, seven and nine-judge verdicts on various constitutional matters including the commerce clause, religion and elections, the ordinance power, triple talaq (where he supports one aspect of Rohinton Nariman’s judgment on merits) privacy, accident compensation, euthanasia, arbitration and use of parliamentary committee reports. These, according to him, were the “best of times (or so it appeared)”. He laments the delay in the Delhi judgement but it arrived after the publication of this collection and, surely, belongs to “the best of times”. What, then, are the worst of times?

Seven Supreme Court judges issuing contempt notices against High Court judge Karnan. But surely Nariman should have taken a stronger stance then. He does not entirely approve of the press conference of four senior judges on January 12, 2014 — protesting the autocracy in allocating cases — saying that Justice Chelameswar’s contrary order of 9 November 2017 was wrong in law, not just prudence.

Confrontations, whether of Bhagwati–Chandrachud then, or now, are to be avoided. To be fair, Bhagwati should have been appointed first. I recall a conversation with Rajni Patel on this, on how Maharashtra law minister Gokhale changed his views to appoint Chandrachud after making clear that this would not happen. But both were good judges. Chandrachud was fair to allow Bhagwati his PIL cause in Court 2. So why, “God save the Supreme Court?” Because it is crucial for democracy, but is at an “all time low”. According to Nariman the citadel never falls, except from “within”. This is unexceptional. I agree with him on Karnan and disagree on the four judges conference. It is the business of the Chief Justice of India (CJI) to bring his team together and heal divisions. Being the master of the roster does not fulfill all the responsibilities of the CJI.

If Nariman is critical about the Supreme Court, he is equally harsh on parliamentary proceedings being broken up by shouting, screaming and running to the well. Many things can be resolved by humour and there is no need for discipline. He admires Nehru and Vajpayee. But have standards fallen? He asks: “Can there ever be ethics in politics?” Of course there can, and must. But rules of ethics have to be framed “not by MPs but those outside Parliament.” This applies equally to lawyers. If “God helps the Supreme Court”, perhaps, also (although he does not say so), God helps Parliament (and the legislatures). This suggestion, that rules of ethics must come from ‘outside’, should not absolve MPs, lawyers and judges from sticking to both an internal morality code they must strictly follow.

Nariman has his favourites. In the Bar, Nani Palkhivala and KL Mishra (former Advocate General of UP), and out of affection and respect, RN Trivedi, also advocate general of the same state, whom we all miss — no less for his sense of humour. He admires Krishna Iyer as “a super judge” and Bhagwati for his juristic craft. He excels as a supporter of minorities and free speech. “Tyranny fears newspapers”, he says, but warns that the media must be free but fair.

Nobody writes as fluently and accessibly as Fali Nariman does. But his book understates the horrible truth that divine help is not just needed for the Supreme Court and Parliament, but Indian governance and democracy, too, with its chaotic existence and lack of distributive justice. A passing thought. Nariman was offered a Supreme Court justiceship. Wonder what he would have been like on the bench.

Nobody writes as fluently and accessibly as Fali Nariman does. But his book understates the horrible truth that divine help is not just needed for the Supreme Court and Parliament, but Indian governance and democracy, too, with its chaotic existence and lack of distributive justice. A passing thought. Nariman was offered a Supreme Court justiceship. Wonder what he would have been like on the bench.

The writer is a senior advocate at the Supreme Court of India

.png)

If Nariman is critical about the Supreme Court, he is equally harsh on parliamentary proceedings being broken up by shouting, screaming and running to the well.

If Nariman is critical about the Supreme Court, he is equally harsh on parliamentary proceedings being broken up by shouting, screaming and running to the well.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario