Staging Gandhi-Tagore letters to teach India how to debate

A play based on the letters Tagore and Gandhi wrote to each other has a lesson on how we can agree and disagree.

Great minds may not think alike: Rabindranath Tagore and Mahatma Gandhi. (Source: File photo)

Come Autumn, the whirring of the charkha, chants of Swadeshi, images burning of “foreign” clothes, the hymn Abide With Me, crackling black-and-white footage from the national movement and three characters on stage will bring to life the turmoil of the last century. But it is not about flipping an old album.

Stay Yet A While, is set to be staged around October 2, to mark the stepping into of the 150th year of Mahatma Gandhi’s birth. Written and directed by Delhi-based MK Raina and narrated by Preeti Agarwal, the play will feature Oroon Das as the father of the nation and Avijit Dutt in the role of Rabindranath Tagore, and rehearsals are on in earnest at a small space in Delhi’s Chhatarpur.

It is not nostalgia that this project is about. The play hopes to show to our charged times how the tumult of almost a hundred years ago was tackled by leading visionaries in its time. Now, as then, fundamentals of coexistence, nationhood, fellowship between human beings are being furiously contested on the streets, on WhatsApp conversations and between all manner of acquaintances and strangers, too.

Raina, the well-known veteran director, playwright, actor and former director of the National School of Drama, who has acted in films like Taare Zameen Par (2007), has been focussing on the use of theatre to heal the conversation in his home-state, Kashmir, for some years. But he believes he must now cast the net wider and that the time is perfect for serving a reminder on how to conduct a debate on nation, nationhood, India and Indianness — things that currently generate more static than sound.

And what better way to stage this robust debate than through letters exchanged between Gandhi and Tagore, from last century? Three characters (a narrator and two others) read the correspondence exchanged between Tagore and Gandhi, with music and archival films as a backdrop, in a multimedia format. In the process, they explore what it means to push the boundaries of ideas and have the patience to accept critique and reframe the argument.

Speaking of his play based on the actual letters and cables which Tagore and Gandhi exchanged, Raina says, “The entire political discourse is muck today. So, I want to foreground this, to highlight how sharp but engaging the dialogue was then — the metaphors, similes and arguments.”

An interesting episode dates back to 1934, when a terrible earthquake in Bihar prompted Gandhi — campaigning at the time against untouchability in south India — to say that the tragedy was about “divine chastisement”, against the sin of untouchability. Tagore, horrified at Gandhi invoking mumbo-jumbo to people already deeply superstitious, wrote to him sharply criticising it, though he said he was not sure if Gandhi had actually said that. But if Gandhi had, then Tagore urged him to treat this as a “letter to the Editor” and to take things forward. Gandhi accepted he had said it and went on to publish it in Harijan, with his own rejoinder. Tagore did not pursue the debate further, but what Raina and his team point out to here, is the fact that this civil to-and-fro was possible between people with a following of millions in their own right. That created a climate for a scientific and logical barter of ideas to take place.

It is not as if the debate was happening at a time of great peace and equanimity. The early 20th century was a time of great shifts, tumult and anxiety, for both India and the world. So, feels Avijit Dutt, the absence of the patience to hold a debate cannot be blamed on 21st century flux. Times were “equally, if not more” difficult then. Dutt, a face familiar to watchers of English theatre in India, as well as from his roles in films like No One Killed Jessica (2011), says it is “anyway an honour as a Bengali to be playing Tagore. But just reading and re-reading the script today is an extraordinarily uplifting experience — the level of debate, the precision with which complex issues are spoken of, and with such candour.”

Another fact brought to light through this is how the discussion was deep and genuine, and how it changed minds and the course of history. “The characterisation of Gandhi as the activist and Tagore as only the artist is also simplistic. The interaction between them was always in both directions. For instance, when Gandhi first went to Santiniketan in 1915, he found the boys and girls seated according to caste groups. He pointed this out to Tagore, who first attempted to justify it, then came around to what Gandhi had to say and changed things around,” says Anil Nauriya, scholar and writer, who has studied Gandhi.

The differences between Tagore and Gandhi are well-known, but what is not, perhaps, that well-known is how they drew from each other. “Tagore had a view on his fasts, but Gandhi, on not hearing from him before one, sends him a telegram, saying, ‘I am walking into fire, but your words matter to me.’ Tagore sends him a telegram right back, to express fellowship,” says Raina.

Speaking of telegrams and cables, former vice-chancellor of Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, historian Prof Sabyasachi Bhattacharya writes in The Mahatma and the Poet (the book is the inspiration for the play): “In the period between the arrest of Mahatma Gandhi in March 1922 and his release in February 1924, the Tagore-Gandhi debate was, so to speak, suspended since Tagore did not pursue his line of criticism when Gandhi was incarcerated. Immediately on Gandhi’s release, Tagore sent him a cable: “We rejoice…”.

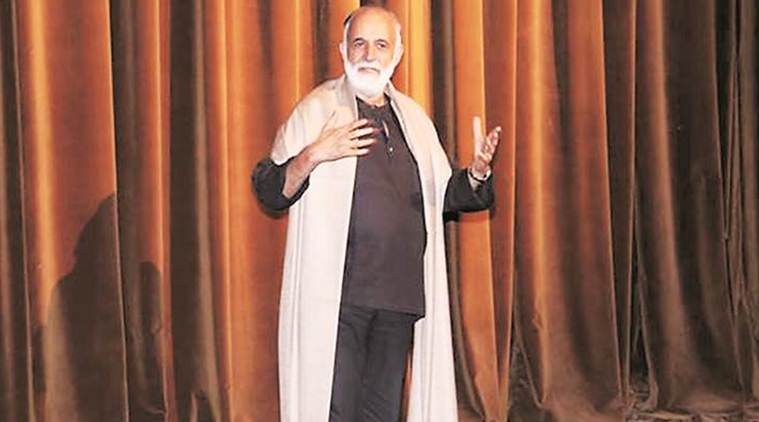

Actor-director-playwright MK Raina.

Actor-director-playwright MK Raina.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario