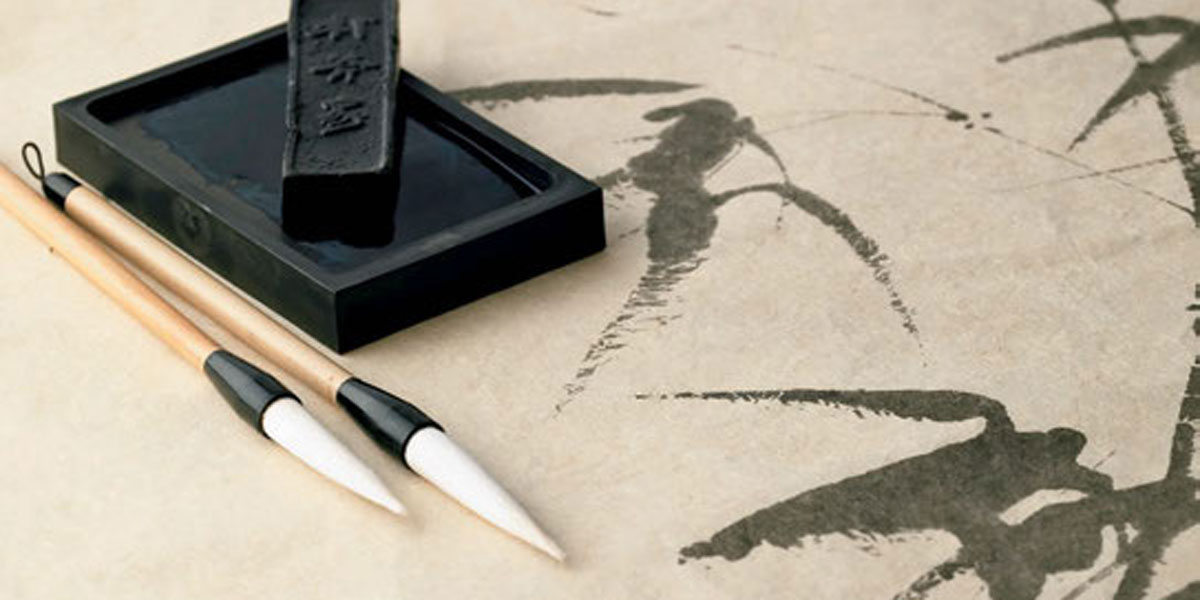

As one of “Scholar’s four treasures”, Chinese rice paper is highly influential for the transmission of Chinese culture.

China’s papermaking: Antique beauty of ancient paper

We regard Cai Lun of Eastern Han Dynasty (25 to 220) as the inventor of the papermaking technology. But ancient paper could be traced at least back to the first and second century B.C. Papermaking technology has provided an important carrier for the promotion of Chinese civilization.

The Palace Museum houses works produced by famous painters of various schools in different periods of nearly 2,000 years from the Jin Dynasties to Ming and Qing Dynasties, each of which has a history of hundreds and even thousands of years. Most of them are written on a kind of paper with ultra-long lifetime, i.e., rice paper.

Paper, as one of the four precious articles of the Study, is an important tool for ancient scholars together with writing brush, ink stick and ink slab. Chinese people value the expression of “articles are for conveying writings and writings for doctrine” and it is based on thin papers that the excellent paintings and calligraphies in China’s thousands of years of civilization history can be well preserved and ancient Chinese wisdom be promoted.

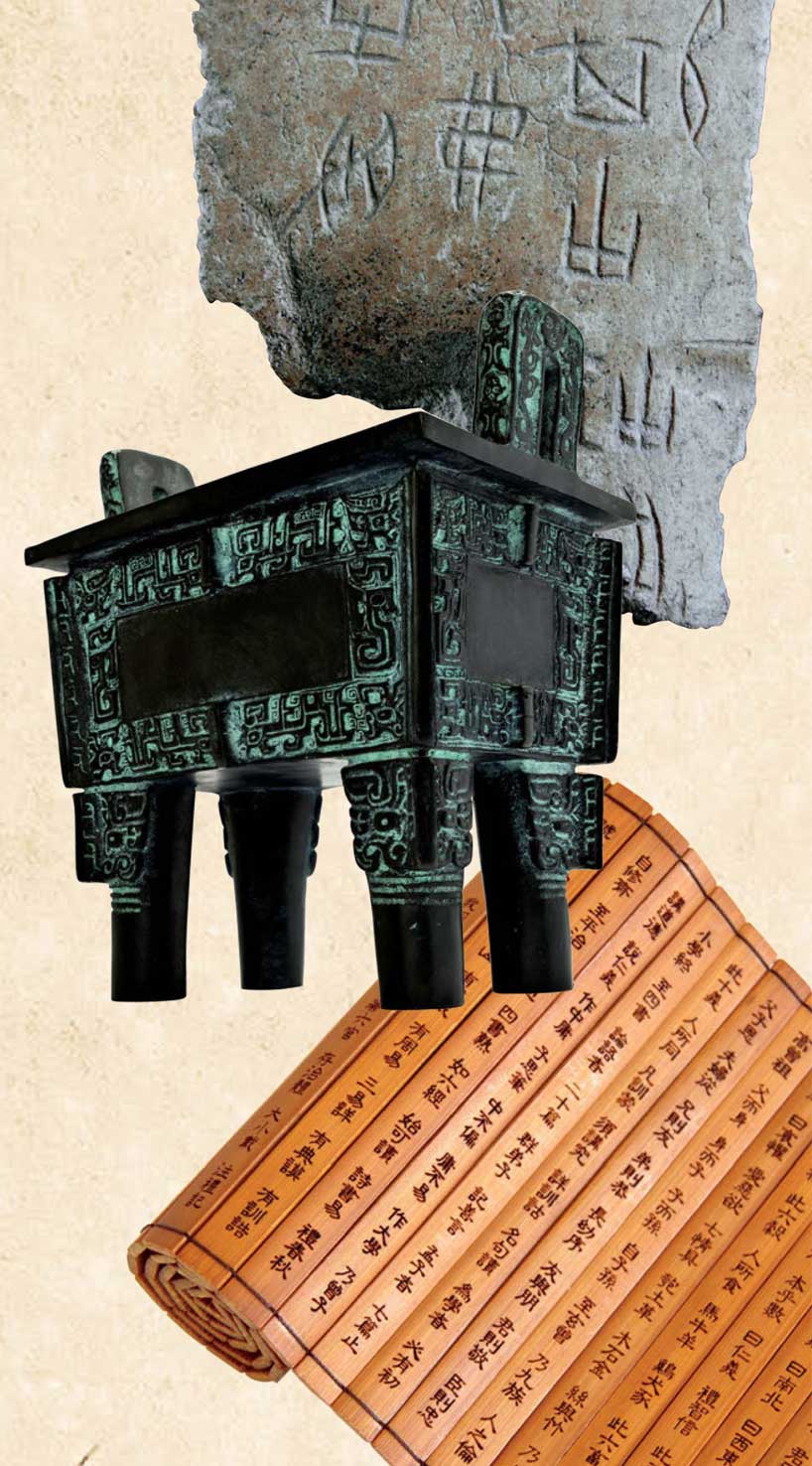

Before paper was invented, tortoise shell, animal bone, bronze ware, bamboo slip, and silk materials had been used in writing. But shell and bone are cumbersome and it’s said that bamboo manuscripts the first Emperor of Qin read every day are as heavy as over 120 jin (back then, 1 jin is about 0.25kg); silk materials are handy yet expensive, making it impossible for extensive usage. In the Han Dynasty as economy and culture developed on a fast track, bone and bamboo slip couldn’t meet social demands accordingly. Paper emerged against such a backdrop.

Thin and cheap paper replaced other materials immediately and became popular painting and calligraphy tool. Reading, copying books (art of printing had yet to be invented) and collecting books were in vogue. During the periods between 265 and 316 in the Western Jin Dynasty, San Du Fu, written by a well-known litterateur Zuo Si, was circulated widely in capital city Luoyang and people acclaimed and transcribed it, driving up the price for paper several times. Finally paper was totally sold out. Many people had to buy paper from other cities to copy the reputed work, leaving the story that “paper becomes expensive in Luoyang, meaning good things make people copy them”.

So, what about the production of Chinese paper?

According to Word and Expression (China’s first dictionary defined by clear-cut logic and system), “paper” is a character with the radical of “silk” which means that paper is mainly made of spun silk materials. For long, we regard Cai Lun of Eastern Han Dynasty (25 to 220) as the inventor of the papermaking technology. But in 1957, Baqiao in east suburb of Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, unearthed a kind of ancient paper which could be traced at least back to the first and second century B.C. which is known as “Baqiao Paper”, much earlier than the era Cai Lun lived in.

Although Cai Lun wasn’t the inventor of papermaking technology, he played an important part in the evolution of the technology. Book of the Later Han – Biography of Cai Lun showed that Cai Lun blazed new trails in papermaking technology, using bark, rag, linen thread, fishing net and other cheap materials as raw materials, which greatly cut back on cost, improved paper quality and created necessary conditions for the generalization of paper.

The modified papermaking technology is recorded in great details via pictures in Heavenly Creations, China’s first-ever encyclopedia about agricultural and domestic industry. To begin with, chopped bamboos are immersed in water so that fiber can absorb water fully. Bark, linen thread, waste fishing net, among other plant materials may be crushed together. Second, stew the crushed materials until they’re tender, making fiber scattered to paper pulp. It’s the key step of papermaking which requires dexterous skills to fish out paper film, which is defined by moderate thickness and even distribution. Finally, overlay paper film, compact it with broad, and put heavy stone on the board to pinch out water; dry off the damp-dry paper film near fire, what is torn off is finished paper.

Later, papermaking technology has been introduced into neighboring countries, such as North Korea, Vietnam and then Japan. In 751, Arabians learned the technology from the Chinese of the Tang Dynasty and spread it across the world. As a result, people in many regions have mastered the technology.

Papermaking technology has provided an important carrier for the promotion of Chinese civilization. Yet, scholars were faced with a new challenge: how to preserve their works through the thin carrier for the long term instead of destruction within few years. Statistics showed that since the Han Dynasty, hundreds of types of handmade paper have sprung up in China. All paper makers are subjected to the same difficulty, that is, how to maximize the longevity of paper while ensuring paper quality.

Rice paper (Xuan Zhi in Chinese pinyin) got its name because of its birthplace in Xuanzhou (Today’s Xuancheng, Anhui Province) and comes as a unique carrier of painting and calligraphy in China. Besides, it is dubbed as “millennium paper” for its ageing resistance, strong tension and invariant color. Song Nian (1837 to 1906), a painter in late Qing Dynsty, wrote in On Painting at Summer Palace that “Rice paper is solid, fine and smooth, when ink is put on, it’s like rain into sand, without free infiltration all the time.” Rice paper is featured by excellent performance in carrying color and water, making it major paper used in traditional Chinese painting. Freehand brush work made its debut in the Song Dynasty which is closely linked with the development and advancement of papermaking technology on top of social and historical reasons.

Painting lovers are also paper lovers at the same time. Li Yu, the last Emperor of Southern Tang Dynasty (on the throne between 961 and 975), was also known as “Master of Ci”. He set up an exclusive papermaking unit under his supervision. Sometimes he even took off the imperial robe (a symbol of ancient emperor) to produce dedicated paper for royal family with craftsmen. The paper is famous for high quality but little availability in the world and called Chengxintang paper as it’s stored in Chengxintang Hall. In the Song Dynasty, Chengxintang Paper was precious with its price as high as gold so that calligrapher of the Ming Dynasty Dong Qichang sighed “I dare not to write on the paper” when he obtained Chengxintang paper.

For now, papermaking technology has gone mechanized. In order to avoid extinction of China’s traditional papermaking technology as a result of modernized production, rice paper has been strictly protected by the state – only “paper made of sandy soil straw and pteroceltis tatarinowii bark in Jingxian County and surrounding areas in Anhui Province by using unique spring water of Jingxian and traditional technique” could be called as rice paper. Even so, the use of traditional paper has been on the decrease. Many young people argue that the economic benefits of traditional technology remain rather low. They prefer looking for jobs outside of hometown to this endeavor, throwing the traditional technique to the dilemma of without successors.

In 2009, the thousand-year-old rice paper making technology was officially added to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, becoming an art performance for more people to understand traditional Chinese culture.

Published in Confucius Institute Magazine

Published in Confucius Institute MagazineMagazine 21. Volume 4. July 2012.

View/Download the print issue in PDF

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario