Written by Pratik Kanjilal |New Delhi |Updated: January 20, 2019 6:00:45 am

Humphry House’s ‘I Spy With My Little Eye’ is a must-read in this season of suspicion

The timing could not be more appropriate, now that the number of fresh sedition charges is in double digits, with a herd of people targeted along with Kanhaiya Kumar, and three intellectuals in Assam, including the much-respected Hiren Gohain.

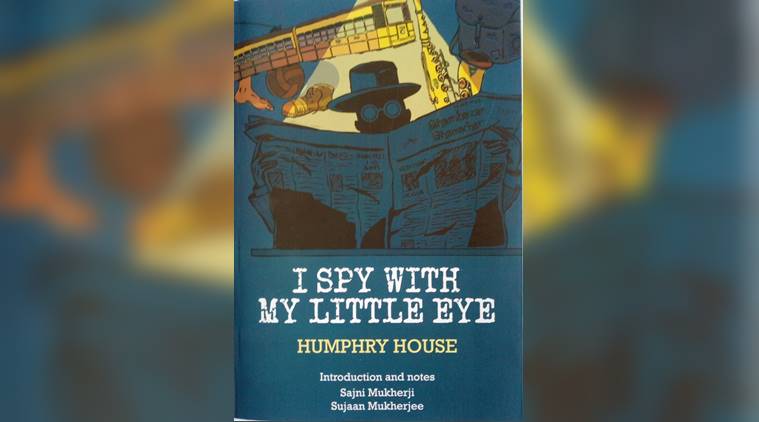

The press of Jadavpur University, one of the many fine institutions which have suffered the unhealthy interest of governments, has just published a new edition of Humphrey House’s I Spy with My Little Eye (edited by Sajni Mukherji and Sujaan Mukherjee). The timing could not be more appropriate, now that the number of fresh sedition charges is in double digits, with a herd of people targeted along with Kanhaiya Kumar, and three intellectuals in Assam, including the much-respected Hiren Gohain. Suspected of being a spy, House was an early victim of the culture of repression, excessive police surveillance and the discouragement of free speech that the colonial administration had let loose in Calcutta in the years leading up to World War II, and his book was a satire of a society under censorship by law, where the intelligentsia were under constant watch.

In fact, House writes of the infamous Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, which criminalises sedition, and which still energises the outrage of editorial writers every other week. He writes of hearing seditious talk on the radio, a snatch from John Milton’s Samson Agonistes (1671): “The brute and boist’rous force of violent men/ Hardy and industrious to support/ Tyrannic power but raging to pursue/ The righteous and all such as honour Truth.” Milton was most appropriate, of course, since Areopagitica (1644), his speech in Parliament opposing licensing and censorship in publishing, was the go-to text for the freedom of speech before it enjoyed this formal name. The satire also quotes Charles Dickens waxing seditious, and declaring his trust in the people rather than their representatives.

Humphrey House (1908-55) was not the typical target of British sedition law, which was designed to stifle opposition to a government of occupation. He was an Oxford man, the founding critic of the modern study of Dickens, and a popular teacher at Oxford and Cambridge. In Calcutta, he had taught at Presidency and Ripon Colleges. But he was different. In their foreword, Sajni Mukherji and Sujaan Mukherjee quote Hiren Mukherjee’s memoir, in which the parliamentarian wrote that House preferred to stay in a central Calcutta hostel rather than an apartment in the “sahib neighbourhood” of Alipore. He consorted with the historian Susobhan Sarkar, and became part of the circle of the poet, critic and journalist Sudhindranath Dutta, who published the literary journal Parichay. They included the poet Bishnu De, the educationist Humayun Kabir, the particle physicist Satyendranath Bose (of Bose-Einstein condensate fame) and Statesman star Lindsay Emerson. A highly seditious bunch, which a repressive government could reasonably fear.

House was apparently tipped off about the government’s interest in him by Michael Carritt, ICS. He was a real spy, close to PC Joshi of the CPI, and leaked state correspondence to tip off activists against whom crackdowns had been ordered. He reported that it had been “provisionally suggested” that House was the “Moscow agent” who had been spotted in Ballygunge, in south Calcutta, “roughly dressed” and sporting a “battered topee in the Eurasian fashion”. In reality, House was just a talented, free-thinking man who did not fit well in the excessively ordered society of his times, and he would eventually be trusted enough by Her Majesty to serve in the war. The non-conformist flourished in the imperial capital of Calcutta in the late Thirties, a period of political uncertainty when Britain was grappling with the nightmares of losing India, and of having to fight a war in Europe. Sir Isaiah Berlin, a friend of House’s from Oxford, read a copy that had reached Britain, is quoted in the introduction: “I tremble to think, what, with his natural rankness of mind and tendency to outgrow with long, dark dank creepers, must have happened to him in the congenial society of a lot of inferior Mulk [Raj] Anands.”

In his slim satire, just 25 pages long, House coined the term “spyarchy” to describe the network of snoops and listening posts which allowed the police to wield power far beyond their mandate. In a course of a short walk across central Calcutta, and a surreal interlude with a priest who morphs into a police interrogator, he presciently describes a strange world of snitches and spooks — precisely what the Soviel Bloc would become after the war. The interrogator brings a damning accusation against the protagonist: “…you write for the Statesman and receive considerable sums of money for the work: is that true?” Elsewhere, the man entraps him with sophistry: “Are you a Communist?” “No.” “What do you mean, no?” “I mean, not to the best of my knowledge.” “Are you then an unconscious Communist?”

House argues that in a snoopers’ state, the police are the best-educated citizens because they read everything that is written. Knowledge is power, which is why Russia now has a professional snoop for a president. There are valuable life lessons in the text for contemporary India, where snooping is increasingly seen as a legitimate function of government.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario