Written by Surinder S Jodhka |Published: January 26, 2019 12:09:56 am

Signposts for the Future

An effort at “unlocking” the essential Ambedkar, to open up a space to discuss the concerns he articulated and wrote about.

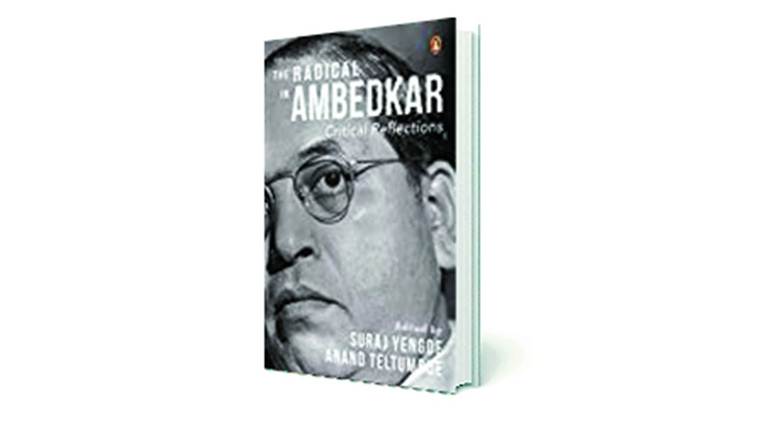

The Radical in Ambedkar: Critical Reflections

Suraj Yengde and Anand Teltumbde (Editors)

Penguin Random House

497 pages

Rs. 999

Suraj Yengde and Anand Teltumbde (Editors)

Penguin Random House

497 pages

Rs. 999

BR Ambedkar was one of the most, if not the most, educated person in India during his time. Though a good number Indians, mostly from the traditionally elite or prosperous families, went abroad to study, not many were awarded PhDs. He earned two, from the London School of Economics in the United Kingdom and another from Columbia University in America. His scholarship did not end with the dissertations he submitted in these foreign universities. Nor did he write only on the question of Dalit emancipation. He was an economist, a legal expert and a social thinker.

He was also more than an intellectual. He had the skills of a journalist and was associated with four newspapers, which he himself had started. He was a prominent educationalist of his time and set up a large number of educational institutions. Even though he worked as a full time member of India’s Constituent Assembly, he remained actively involved with the movement for Dalit rights. Most importantly, perhaps, he wrote on a wide range of subjects and his writings were almost always shaped by the demands of the subject at hand and not by his political activism.

While his deification by the Dalit masses across the subcontinent and beyond is understandable, it also makes him inaccessible for critical engagements that would advance our understanding of the range of subjects he had been preoccupied with and wrote books and articles on. Since the early 1990s, Ambedkar has grown in stature and everyone from the right to the left wants to appropriate him. He has also emerged as the most popular symbol of the Indian state. The number of universities, colleges and other public institutions/building named after him will, perhaps, surpass any other political leader in recent times. Compare this with the fact that when he died in 1956, his friends and followers had to partly pay for taking his body from Delhi to Bombay.

However, the editors of the book underline that this elevation of Ambedkar needs to be accompanied by recognition of his intellectual contributions, of the ideas and opinions on what ails our times and building a society free of discrimination and divisions. For this to happen, Ambedkar needs to be available for critical engagement, even scrutiny, by scholars and thinkers of contemporary times. In absence of such constant critical engagements with his ideas and scholarship, Ambedkar becomes amenable to appropriation by the ruling classes as a brand ambassador. The editors are particularly critical of him being eulogised as the “messiah for Untouchables, a Constitution maker, a Bodhisattva, a neoliberal free-market protagonist…”. In the same breath, he is also unjustly “vilified as being casteist, a British stooge and a communist hater” (p. xxiii). Besides the possible political motives, such misrepresentations of Ambedkar are also a result of a lack of serious engagement with his works.

Thus, this book is an effort at “unlocking Ambedkar”, to open up a space where he and his writings become a rallying point for scholars, thinkers and activists to discuss the questions and concerns he articulated and wrote about and what they can learn from him. Unlike many other thinkers and theorists of modern times, Ambedkar did not believe in any fixed ideological system. Nor did he attempt to produce one. His approach to social problems was that of pragmatist. Such an approach or perspective does not necessarily advocate consistency, which he famously dismissed as “the virtue of an ass”. Context and circumstances thus need to be taken into consideration while contemplating policy or political actions.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario