Inside a Mumbai police station, everyone is a character, and the city a story

Mumbai, through a crime reporter’s diary, is full of anecdotes, of helplessness, and the realisation that we are all on the edge, and we were always fragile.

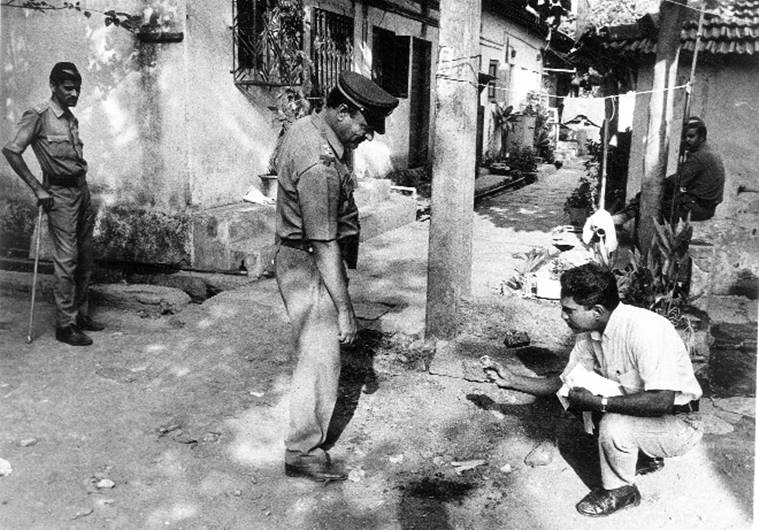

Games people play: Policemen at a riot scene.

Once, on a journey to Agra, many moons ago, travelling to see the Taj Mahal, a fellow traveller and a Hindi cinema buff, had a question. Is Simi Garewal always as “white as Taj”? Does she wear white “even in the privacy of her home?”

Bombay, for him, was a place where the rich could afford their fantasies; a city which lived through its celebrities.

In the years I have spent here, as a resident, as a news chronicler, the city has always been a conversation starter.

Everyone has a Bombay inside them, a memory, a corner, a spot to catch their Arabian. The city is such a habit, that everyone has a favourite view, too.

I know someone whose best-loved view of the city is from the window seat of a flight about to land — the first sight of squares of tarpaulin spread across its suburban slums; the blue, both calming and deceptive. If the blue of the slums is struggling, the blue of the Arabian Sea is an aspiration.

Bombay belongs to everyone.

As a news chronicler, I saw the city through another lens. I was a crime reporter, and in 2003, I started calling the city Mumbai.

Mumbai, for me, was best studied from inside a police station. This is where the city’s good, bad and ugly came face-to-face with the uniform’s good, bad and ugly. If the sea cuddled us, it’s the police stations where our emotions choked. The drama was always biting. The regret always loud.

Every day took me to a different police station. There were the ornate stairways of the Raj-era stations of south Mumbai; and the old rundown ones, where constables would use their tiffin boxes to shield their tables from the pouring rain. There were police stations in old housing colonies, where young boys smiled and chatted on mobile phones on balconies above, and women threw down kitchen waste wrapped in plastic bags.

My favourite was the Yellow Gate police station, where the most exciting seizure, a Bollywood actor’s car, was used by the neighbourhood cats as their delivery room.

Every day, in these police stations, I heard stories. Of sex and drugs. Of mobs and fear. Of water cuts and power failures. Of fights over a cricket ground. Of humans killed by vehicles. Of lovers being public nuisances. The mood swung from the uplifting to the dire, from the slap on the back for “changli (good) detection” and the stoic acceptance of “woh toh off ho gaya (he is dead).”

The police station’s interrogation rooms are sweaty, and often have dogs and cats sleeping without a care, even as someone’s knuckles are being broken inside. Here, I have seen a cop’s instinct match a criminal’s stubbornness; on rare occasions, they have shared ketchup and snacks during lunch hour.

The thana was where the cops made sense of crime as they recorded it meticulously in Scotland Yard’s Latin terminology, though they always detected the case in their heads in Marathi and solved it with common sense. Try listening to a Mumbai constable say modus operandi and rigor mortis! Actually, try listening to his old-world philosophy, where Karna, Duryodhan, Allah, and Jesus are all invoked in one room, as and when needed. Ram and Ravan, too. That was how a Dongri police officer tried to get through to a 20-year-old, who had been dragged into the station by his father. Ram and Ravan were the “good cop and the bad cop,” he said. And if he didn’t own up to the fact that he had thrashed his mother, the cop would have to turn into one of the two.

One of my most difficult memories was of the mother of a rape victim who sat near a small-time thief-turned-informer at Oshiwara police station. They sipped cutting chai together, no one speaking a word. Till the boy said, “If you allow me, then I know people who can give justice. They are outside this police station.” The police officer heard, and he didn’t blink.

This is also where I once saw humanity. A father of a boy, who had been stabbed to death, came up to the investigating officer and gifted him a Quran. The case was never solved even after a year, but the father wanted closure, for himself and the officer.

I didn’t understand it then. I would, years later, when I heard Valerian Santos calmly speak about the death of his son, Keenan — stabbed along with his friend Reuben by a group of molestors. His deadpan narration, even after a year of the 24-year-old’s death, had me break down in tears. Santos was the one who consoled me, by handing me a Bible.

One comes to a police station, when one loses something. And sometimes everything. A mobile phone. Memory. A mangalsutra. A television set. Dignity. An eight-year-old daughter. A 60-year-old father. Life. Speakers from a Ganesh pandal. A family car. A postcard. Sometimes, even sanity. Not everything is found. And, if you ask a Mumbai police constable, he will also tell you philosophically that not everything should be found!

A police officer in Dadar once told me that his biggest nightmare is the mangalsutra theft. No matter what the status of the complainant, a mangalsutra robbery is always reported. “Because the Indian Penal Code doesn’t record emotions and relationships, only crime. We then have to listen to the stories too,” he had said, of the many times he has had to comfort a crying adult, who believed the theft was a bad omen.

Death is never a climax at the police station. It’s where the story begins. My first body was not of an Indian. It was a Nigerian man, who had overdosed. The Colaba Police lugged his bloated body, with the legs spread apart, as rigor mortis had set in, from one hospital to another, armed with just two bottles of cheap perfume. That stench never left me, or the two constables who escorted that body. It’s been over a decade.

The bodies have only piled up. I keep a mental note of the deaths in my head. In reporting on the city for 15 years, the bodies tell us the extent of the pain and hatred it is capable of. Sometimes, it’s a fight between the city’s old and new migrants. At times, the script is dictated by religion and the mob. There are bodies you wish you never saw. An explosion and a burnt victim. A five-year-old raped, a broom inside her.

But there are moments when the city holds you. During the July 2006 rail bombings, it was the blue tarpaulin, that one sees from high in the air, that was pulled down by slum-dwellers and used as a makeshift bag for the scattered limbs and bodies. No movie will show you that. Those are the moments when I have seen my city from up close.

Crime makes one vulnerable, and Mumbai is the most fragile in those moments, having been savaged, again and again. The most horrifying cases are not the ones which make headlines, not always. Gangs make for a stunning narrative, but so does the ordinariness of everyday crime.

As I visited the police stations, over the years, I began to think of them as monuments of loss. In the city’s 93 monuments, with their own yellow borders and prejudices, our collective losses are archived. The grief of a loss never ebbs, and if a story has been officially recounted to a policeman, it probably never will. Like the roots of the trees, Mumbai’s cops and their informers keep the city in place. Inside a police station, everyone is a character, and the city a story.

The FIR was once described to me by a Mumbai police constable as a document of greed. “It’s the height of a city’s hunger, its greed,” he had said, with a chuckle. Mumbai doesn’t do ordinary crime. We think maximum in this city. Those are the stories in the summary pages and margins of the FIRs: The stories of underworld. Of the routes weapons take. Of the strange friendships in this city. Of the many ways a wife can kill a husband. Of the boxes of bodies that turn up in its national park.

We were tracking the lives of the 188 people who had lost their loved ones in 7/11, when a widow asked me, “What did I get, speaking to victims about their dead ones?” I still do not have an answer. No crime reporter actually does. None of us enjoy this. Pain is the most difficult to write. Especially, when you are shown a tube of Fair and Lovely, purchased as a gift by the wife for her husband, on the same night that she gets a call that his body will return home. A friend calls me on each 26/11 anniversary. She can still hear the gun shots.

Mumbai, through a crime reporter’s diary, is full of anecdotes, of helplessness, and the realisation that we are all on the edge, and we were always fragile.

Brigadier G Natarajan became the face of the 1993 blasts, when the black-and-white photograph of him — standing outside the Air India building, clutching his stomach and pants, minutes after the sixth bomb had exploded near him — was splashed in this newspaper. Later, he told me that despite the trauma he had suffered, he wanted to return to Mumbai. “It is only here that my wife can still take a BEST bus from Ghatkopar to Marine Drive and still be safe. I still have tremendous faith in its people,” he said.

The city will always be a good space, where all of us can co-exist. But if anyone tells you that it was never this difficult here, do not believe them. Mumbai is as deceptive as its people. I can vouch for that.

For all the latest Eye News, download Indian Express App

.png)

Cops trawl for evidence after a shootout with the Chhota Rajan gang in 1996.

Cops trawl for evidence after a shootout with the Chhota Rajan gang in 1996. A bomb being defused at Chowpatty in 1999.

A bomb being defused at Chowpatty in 1999.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario