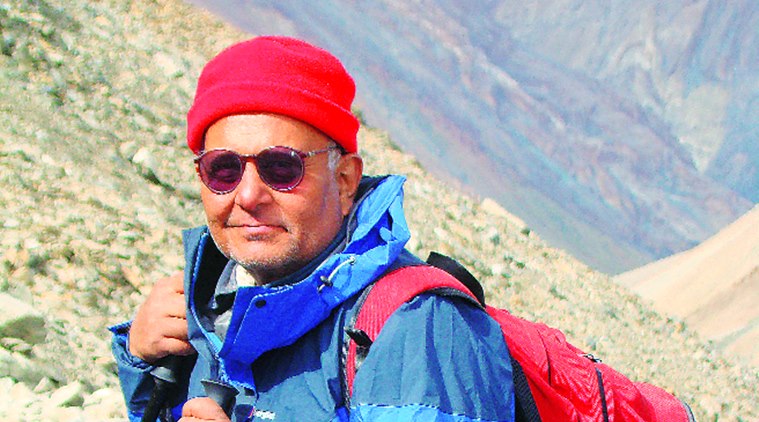

Mountain Man: Author Harish Kapadia on his adventures in the Himalayas

Mountaineer-author, Harish Kapadia, 72, who has been editing the Himalayan Journal for 37 years, has written books such as Siachen Glacier: The Battle of Roses, Spiti: Adventures in The Trans-Himalaya, Exploring The Hidden Himalaya, among others.

In the book, Kapadia writes that since Dhaula Dhar offers varying degrees of difficulties, Col JOM Roberts had prophesied that many climbers from the world or India would use the range for adventure.

Sometime in 1929–30, when Dutch explorer PHC Visser and his team were on their third journey to the mighty Karakoram range, they received a note from Dr Longstaff: “When it is desired to survey this unknown corner, will the party please proceed five miles up the Siachen glacier and take the first turning on their right?” Visser followed this cryptic advice, which led to the discovery and survey of the Terong valley. The valley was more or less forgotten, until 1984, when in the midst of the Siachen war, an Indo–British team explored and named many peaks in the area. Years later, the account of their journey, along with several others, have been reproduced in the book Legendary Maps from The Himalayan Club (Roli Books, Rs 1495), edited by Harish Kapadia, to celebrate 90 years of the club. The book contains 55 maps from various editions of the Himalayan Journal, which cover areas in Kashmir, Karakoram, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Nepal-Tibet, and Sikkim-Arunachal Pradesh-Bhutan regions, through stories of various expeditions written by army officers, surveyors and mountaineers, and sketch-maps that depict the route of a trek, the face or ridge of a mountain climbed, the places where camps were established and the spots where accidents occurred. Some of the routes and climbs documented in the book are yet to be repeated.

The Himalayan Club, based in Mumbai and established in 1928, is one of the oldest clubs in India and the world. “There were very few Indians in the club initially. In 1947, when the British left, people thought that mountaineering and the club will not hold up in India. Then in 1951, a Doon School teacher, Gurdayal Singh, and few others went on a trek to the Trisul peak in the Kumaon region. That’s how Indian mountaineering took off,” says Kapadia.

In the book, Kapadia writes how Kashmir was the first of the Himalayan areas to attract climbers, and British officers stationed in Rawalpindi, Murree or Muzaffarnagar — now all in Pakistan — could reach Srinagar easily. “Till 1989, before the conflict escalated, Kashmir was the easiest place go to, it was a favourite among trekkers and mountaineers,” says Kapadia, who has covered the region in many treks. He has also visited the Siachen glacier about nine times. “When we went for the first time, in 1984, Indian army had already landed and the war was going on, we could hear the firing,” he says. The glacier, touted as the highest battleground on earth, lies in the Karakoram range. The section about it starts with a piece by Italian mountaineer, Reinhold Messner, who recounts his experience of spending the night on Nanga Parbat in 1970. He lost his brother Gunther there. The body was found in 2005.

The book also touches upon the smaller treks in the Dhaula Dhar range, and Nanda Devi, Kumaon, Papsura and Garhwal regions in Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. In the book, Kapadia writes that since Dhaula Dhar offers varying degrees of difficulties, Col JOM Roberts had prophesied that many climbers from the world or India would use the range for adventure. These areas are now extremely popular among city dwellers. Roberts, in 1938, visited Triund, and there is also a mention of the popular village Malana, in Himachal’s Parvati valley, in another chapter. Kapadia remembers his trip to Triund in 1973. “Tab wahan kuch nahi tha (There was nothing there). There used to be a bungalow and we used to stay there for two-three days and return. Now it has become crowded,” says Kapadia. “Most people go to the same 50-60 places, if you’re a real trekker, go to real places, then there won’t be many people. You have to select your place well,” he says, advising budding trekkers. In the journal, Kapadia will now make an addition — use a special symbol to indicate if the place will get crowded on weekends.

Kapadia, 72, who has been editing the Himalayan Journal for 37 years, has also written books such as Siachen Glacier: The Battle of Roses, Spiti: Adventures in The Trans-Himalaya, Exploring The Hidden Himalaya, among others. He started trekking in 1963 with a trip to Pindari glacier and Har ki Dun in Uttarakhand. He later trained at Himalayan Mountaineering Institute and Nehru Institute of Mountaineering in 1964-65, and in the last 50 years has covered 30 peaks and 150 passes in the Himalayas. In 2003, he was honoured with the Royal Medal by the Royal Geographical Society, to become the first Indian to receive the award after 125 years. In the same year, he was also honoured with the Tensing Norgay National Adventure Award, the highest adventure award in India. In 2017, he was awarded Piolets D’or Asia, considered to be the Oscar for mountaineering.

Kapadia continues to trek. His last trip was at Nichar Valley, in the Kinnaur region of Himachal Pradesh, a few months ago. “I made it a point to not repeat an area that has already been covered by me. Even after 50 years, everything is not over yet,” he says.

For all the latest Lifestyle News, download Indian Express App

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario