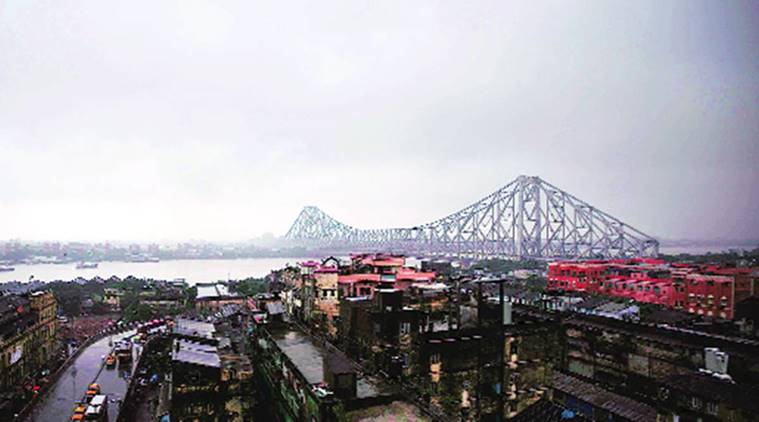

A Kolkata cop throws light on the city’s darkest murder mysteries in his new book

A Certain Justice: The Kolkata Police Facebook page had been popular already, says IPS officer Supratim Sarkar, and, initially, the page updated regular crime stories in a “reader-friendly” format. But the readers wanted more.

IPS officer Supratim Sarkar talks about Kolkata’s Pakur case and more!

In 1932, a gramophone pin gripped the imagination of Bengalis obsessed with crime and mystery. Byomkesh Bakshi, writer Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay’s iconic literary detective, had come across a baffling case in Pother Kanta (Thorn on the Path), in which the killer use a bicycle bell as a spring gun to shoot people with gramophone needles in busy thoroughfares.

The same mechanism was employed by another criminal two years later, in what is now registered as the Amarendra Pandey murder case (or the Pakur murder case) in the archives of Kolkata Police. Pandey was killed by his brother, Vinayendra, with an injection containing the lethal plague bacteria in the middle of a crowded railway station. “When I wrote about the Pakur case, I got asked about the connection a lot,” says Supratim Sarkar, a 1997-batch IPS officer and the current additional commissioner of police, Kolkata, “Personally, I think it was just a strange co-incidence but then again, you never know!”

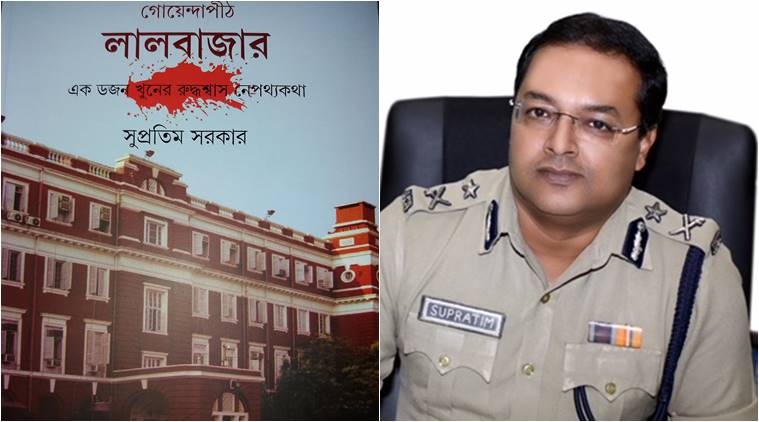

The fact that we never quite know is also the irresistible allure of crime thrillers. Sarkar is acutely aware of this. Last year, in July, he started a weekly series for the Facebook page of Kolkata Police, #Rohossyo Robibar (Sunday Mystery). Each Sunday, an old case file drawn from the city’s archives was published. The “stories” received a strong enough response online to be eventually made into a Bengali anthology featuring 12 cases, Goyendapith Lalbazar: Ek Dojon Khuner Ruddhaswas Nepathyakatha (The Mysteries behind a Dozen Murders, Ananda Publisher, Rs 249). The book, and its translation, Murder In The City (Speaking Tiger, Rs 299) was launched at the Kolkata Book Fair this year.

The Kolkata Police Facebook page had been popular already, says Sarkar, and, initially, the page updated regular crime stories in a “reader-friendly” format. But the readers wanted more. “Everyone wants to know how a case is solved. The crime branch is like the bedroom or kitchen which people don’t normally have access to… so we started posting about thefts or burglary cases.” People began to appreciate the presentation and requested that Kolkata Police should draw on old case files for the series. Sarkar asked the commissioner of police, Rajeev Kumar, and after getting an enthusiastic approval from him, set about writing down one grim narrative after another.

Of the 12 stories featured in the book, it was the Pakur case that flummoxed Sarkar the most. “It’s incredible that in 1934 somebody would plan to kill his brother by injecting him with plague bacteria! Which is why, one court judgment of the case says that it is unique in the annals of crimes across the world. The planning was amazing… it would have been projected as a normal death with no post-mortem, as plague could have been contracted anywhere,” says Sarkar.

Of the 12 stories featured in the book, it was the Pakur case that flummoxed Sarkar the most. “It’s incredible that in 1934 somebody would plan to kill his brother by injecting him with plague bacteria! Which is why, one court judgment of the case says that it is unique in the annals of crimes across the world. The planning was amazing… it would have been projected as a normal death with no post-mortem, as plague could have been contracted anywhere,” says Sarkar.

Less ingenious but more gruesome cases also feature in the book. In the Belarani Dutta murder case of 1954, for example, the body parts of a woman, chopped up into pieces and stuffed into four newspaper packages, were discovered around the Kalighat neighbourhood. The culprit, a man called Biren Dutta, had led a double life and unable to handle the financial burden, had killed one of his two wives, Bela, who was nine months pregnant.

In all the stories, however, it isn’t as much the detection of the criminal as following the trail of evidence to build a watertight case that is more important. “Fictional investigations mostly conclude at this point,” writes Sarkar in the Pancham Shukla murder story (1960) in the book. But, for “the real sleuths of Lalbazar, the job after the arrest is of paramount importance too.” In the Shukla case, the cops got the confession to the murder of Shukla — a security guard — early on from Ramlochan, an acquaintance of his. It had been aided by a breakthrough: the investigator-in-charge had to resort to a photographic superimposition — the first time the process was used in the country to identify a victim — to actually establish the crime and identify the decomposed body of Shukla, who had been killed and dumped in a shallow lake. These are the cases where, says Sarkar, the steady, staid police processes trump the instant, sexy deductions of detectives in popular culture. “My main contention is that fiction is different from real life. The fictional sleuths are artists and we are the artisans. For us, it is sheer hard work and perseverance that help us crack a case,” he says.

With exclusive access to the city’s crime history, and real-time access to the crimes of the present day, how does Sarkar view the evolution of crime in the city? Is it any different now? “In a way, it is different,” Sarkar says. “When you go through the case archives of Kolkata police 10 years ago, the usage of technology by investigators was obviously much less. Cyber surveillance by cops now has changed that, and the usage of tech even by criminals has ensured it cuts both ways.” The motives, though, remain the same. Sarkar points out the four Ls behind almost every crime: love, lust, lucre and loathing. “I am quoting PD James’s The Murder Room, but the motives haven’t really changed.”

And who are the detectives the real-life sleuth has grown up admiring? Says Sarkar, “Agatha Christie, followed by PD James, GK Chesterton and Arthur Conan Doyle. Everyone talks about Christie’s Hercule Poirot, but I like Miss Marple’s stories more. Her ability to recollect and connect the dots simply, with clarity, is something I have always liked.”

For all the latest Eye News, download Indian Express App

.png)

Tell me your nightmares: Additional commissioner of police, Kolkata, Supratim Sarkar.

Tell me your nightmares: Additional commissioner of police, Kolkata, Supratim Sarkar.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario